Dragon Ball's True Genre: We Need to Talk about Wuxia

Moderators: General Help, Kanzenshuu Staff

- Kunzait_83

- I Live Here

- Posts: 2974

- Joined: Fri Dec 31, 2004 5:19 pm

Re: Dragon Ball's True Genre: We Need to Talk about Wuxia

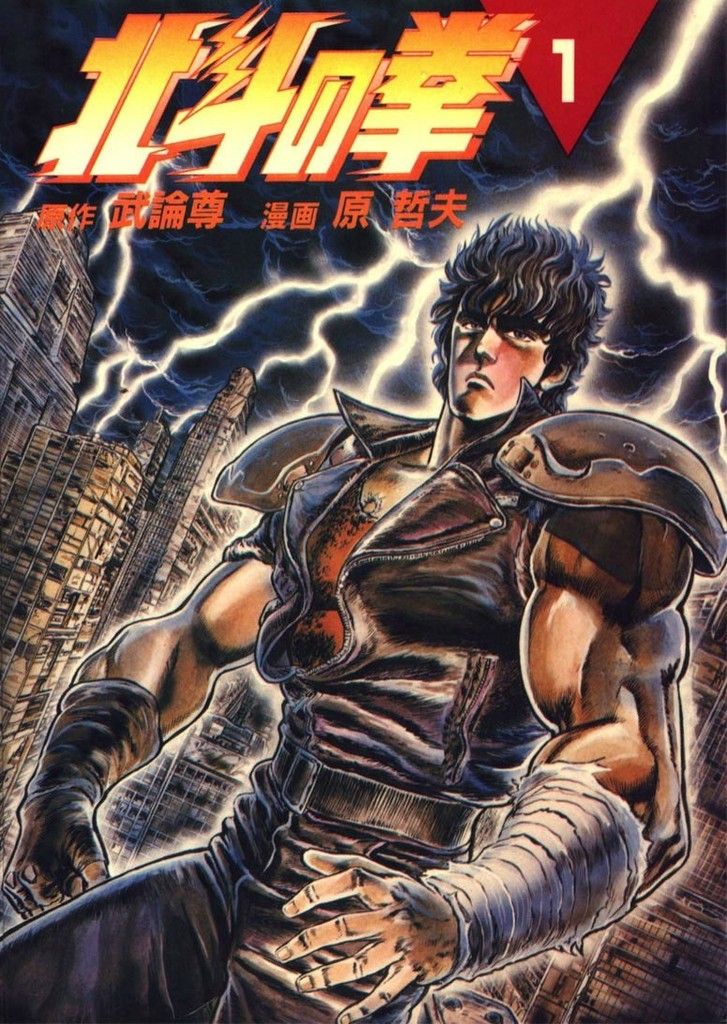

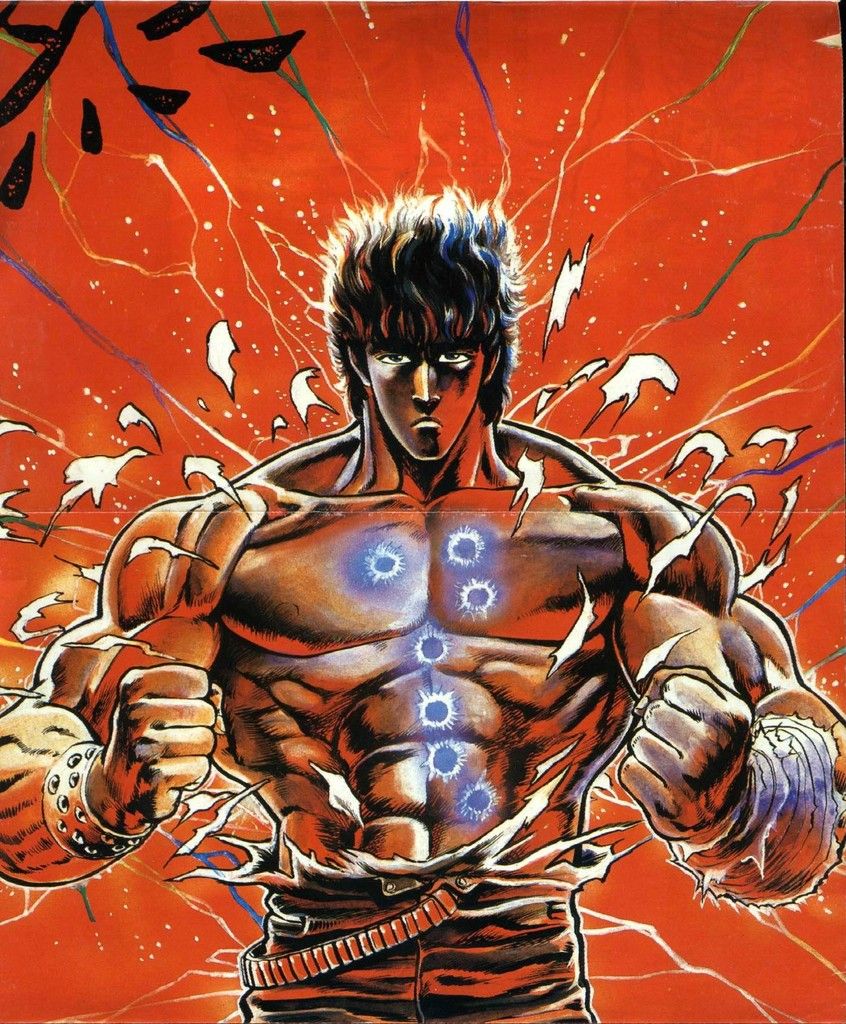

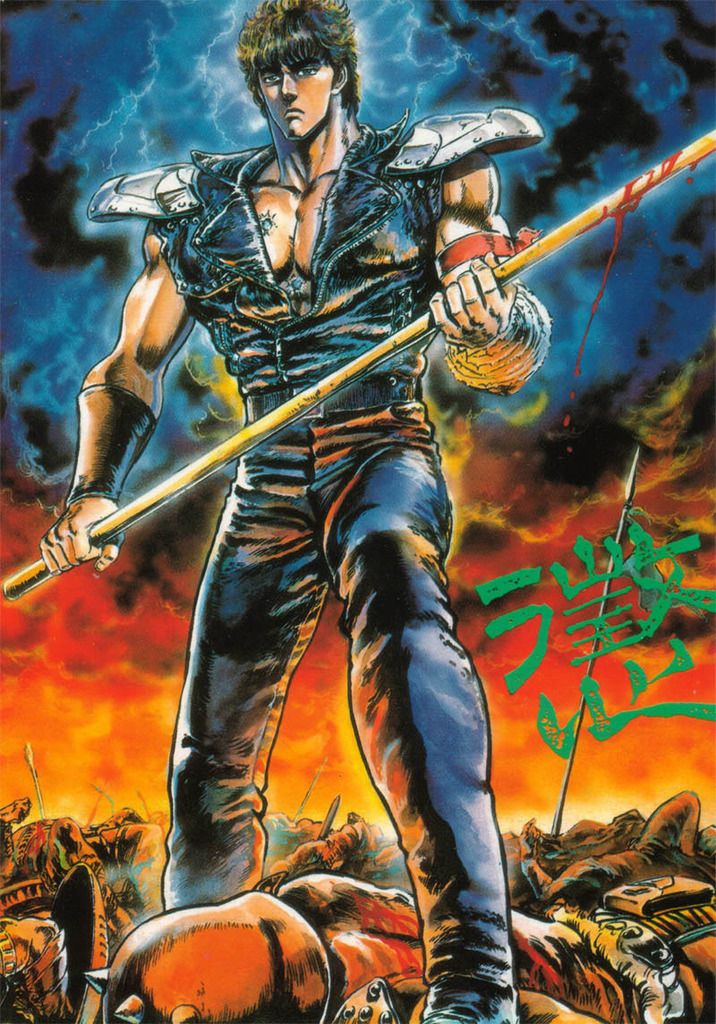

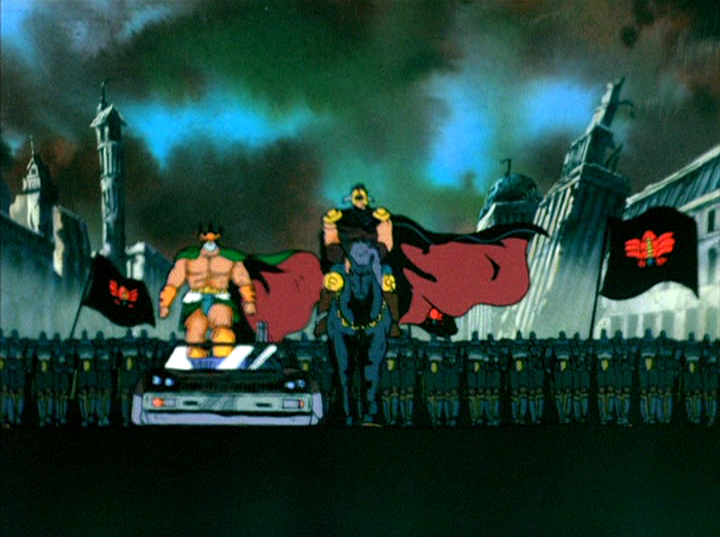

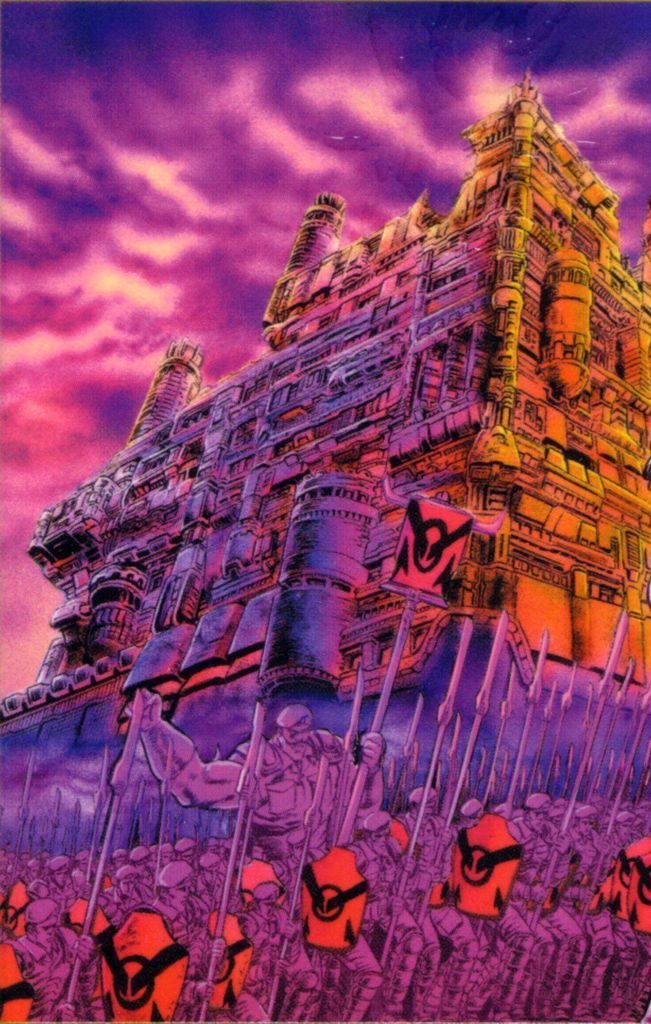

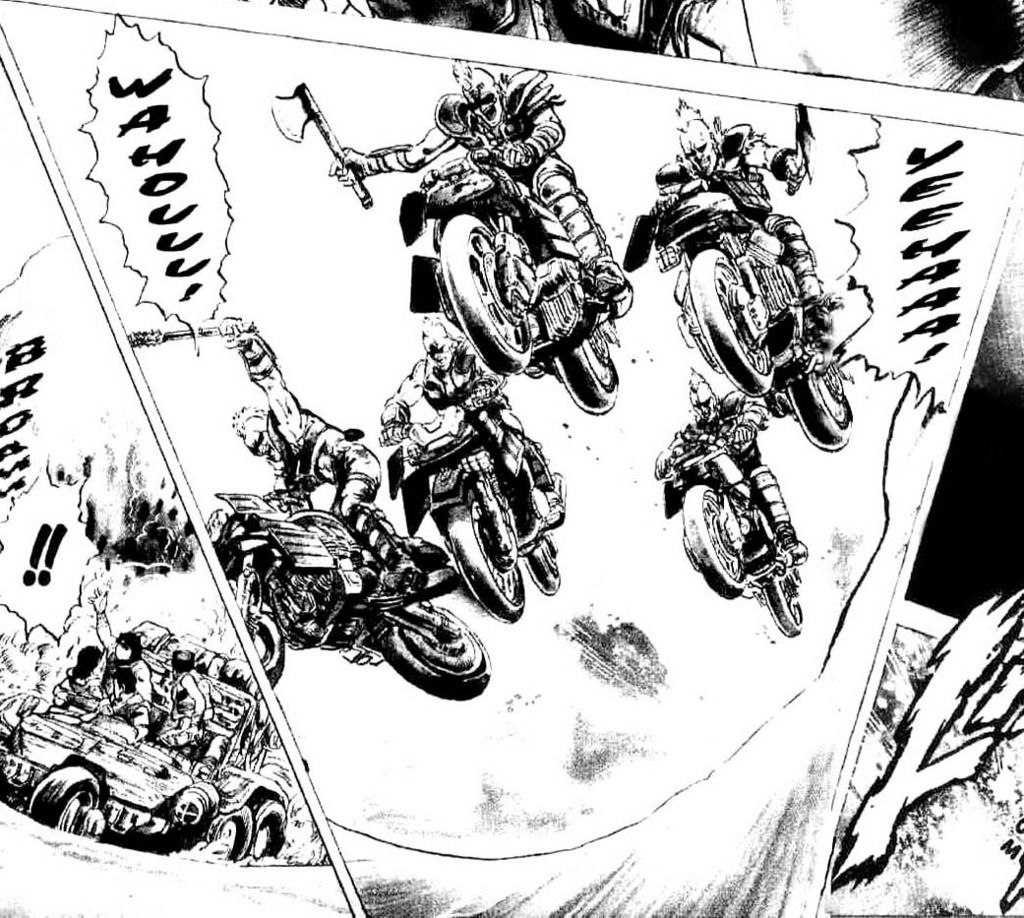

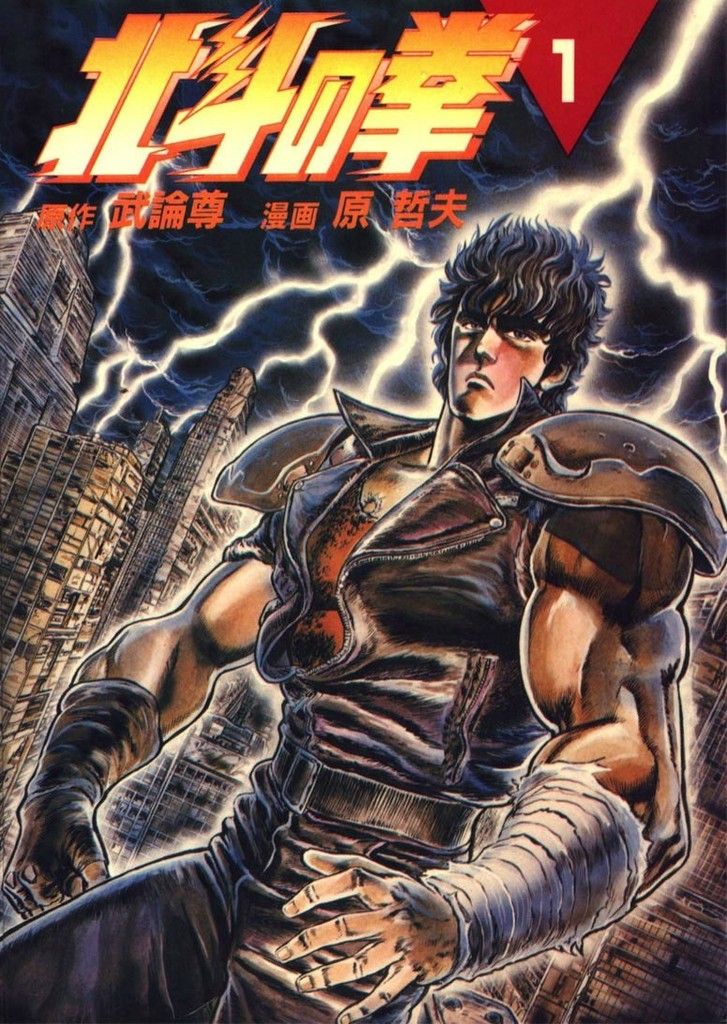

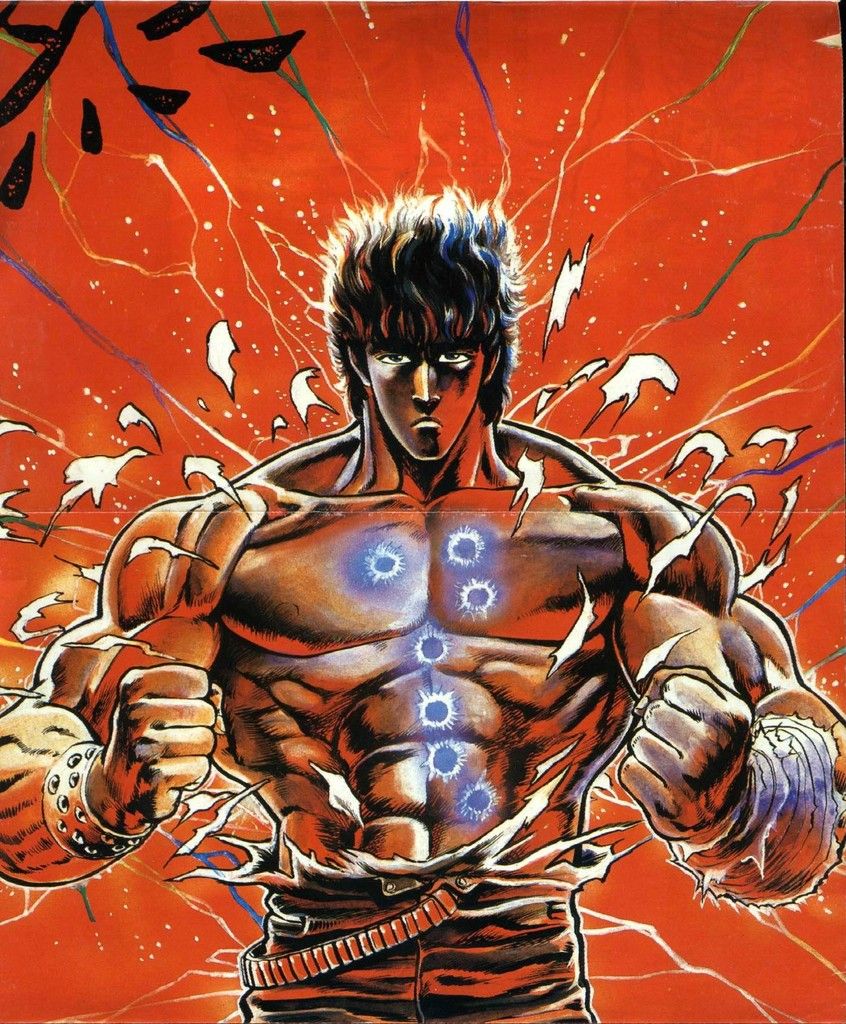

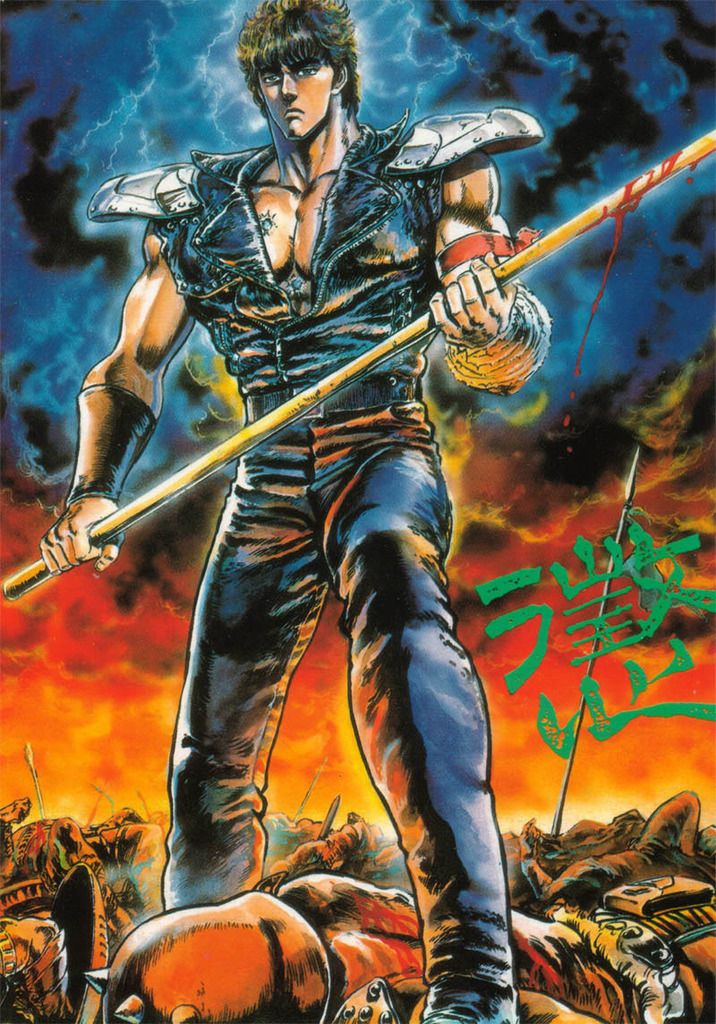

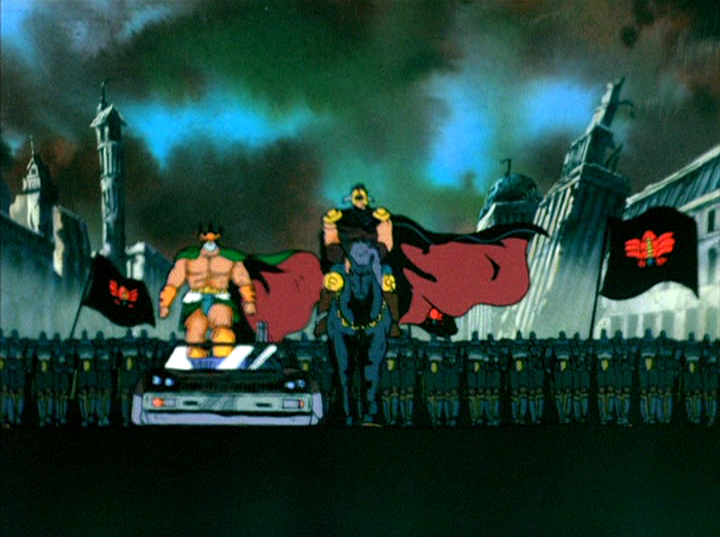

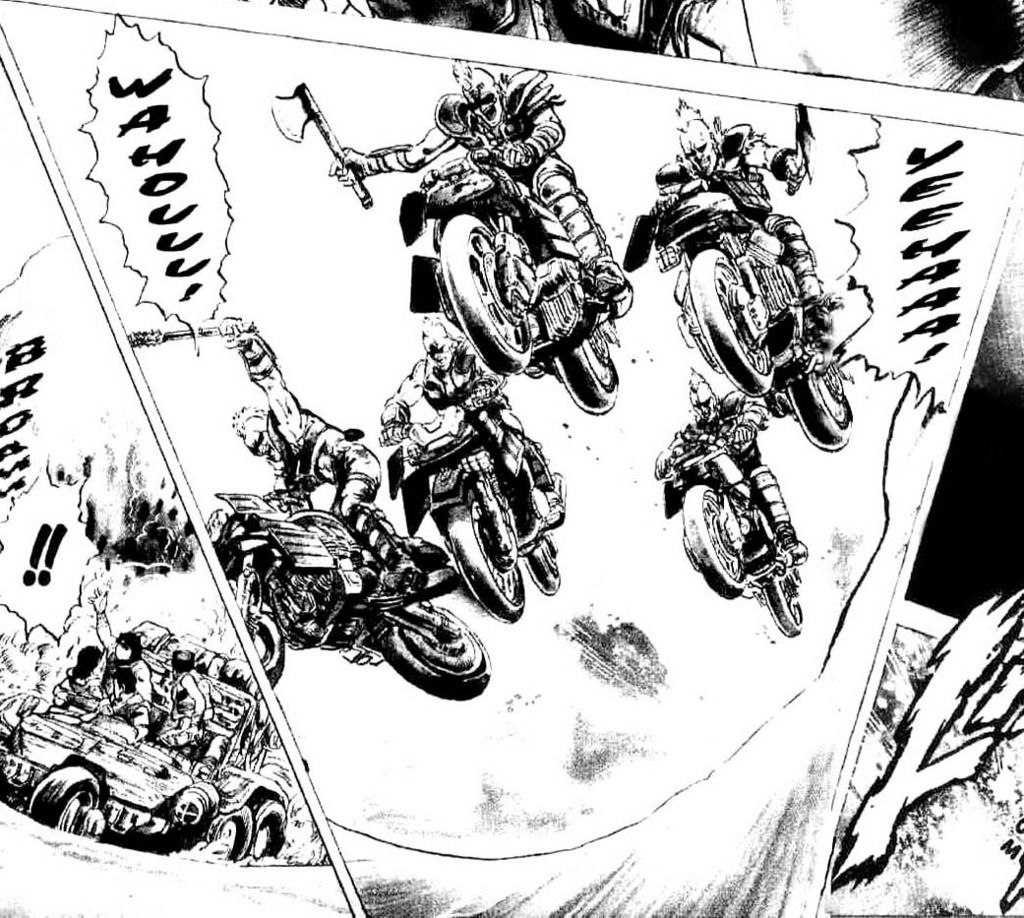

The subsequent parts of this whole diatribe go into not only Fist of the North Star, but also plenty of other examples of Wuxia across various nerd media over and throughout the years. Believe me, I don't leave too many stones unturned.

Oh hey, speaking of which... page 2!

Oh hey, speaking of which... page 2!

http://80s90sdragonballart.tumblr.com/

Kunzait's Wuxia Thread

Kunzait's Wuxia Thread

Journey to the West, chapter 26 wrote:The strong man will meet someone stronger still:

Come to naught at last he surely will!

Zephyr wrote:And that's to say nothing of how pretty much impossible it is to capture what made the original run of the series so great. I'm in the generation of fans that started with Toonami, so I totally empathize with the feeling of having "missed the party", experiencing disappointment, and wanting to experience it myself. But I can't, that's how life is. Time is a bitch. The party is over. Kageyama, Kikuchi, and Maeda are off the sauce now; Yanami almost OD'd; Yamamoto got arrested; Toriyama's not going to light trash cans on fire and hang from the chandelier anymore. We can't get the band back together, and even if we could, everyone's either old, in poor health, or calmed way the fuck down. Best we're going to get, and are getting, is a party that's almost entirely devoid of the magic that made the original one so awesome that we even want more.

Kamiccolo9 wrote:It grinds my gears that people get "outraged" over any of this stuff. It's a fucking cartoon. If you are that determined to be angry about something, get off the internet and make a stand for something that actually matters.

Rocketman wrote:"Shonen" basically means "stupid sentimental shit" anyway, so it's ok to be anti-shonen.

- Kunzait_83

- I Live Here

- Posts: 2974

- Joined: Fri Dec 31, 2004 5:19 pm

Re: Dragon Ball's True Genre: We Need to Talk about Wuxia

Part 4: Wuxia in Modern Media

Before we proceed any further into this, at this point I'd like to take a moment to apologize for how generalized I've kept large swathes of this whole info dump session thus far. But you have to understand something: at the risk of repeating myself and belaboring a point here, it can never be overstated the palpably overwhelming degree to which Wuxia is a MASSIVE fucking genre with an INCREDIBLY dense and rich history and array of individual stories and various retellings and reinterpretations of many of those stories spanning back countless centuries across SUCH an insane array of storytelling mediums.

Towards the end stretch of my tenure as a regular here, as I'd come to realize how staggeringly ignorant of this entire genre's existence much of this community (and wider modern Western Dragon Ball fandom in general) was and started talking about it a bit more in some of my later posts (almost coming within a hair's breadth at one point of appearing on the podcast to talk about aspects of it) I'd gotten the distinct, overwhelming impression from various other regulars here that I was beginning to be seen around these parts as some sort of resident “Kung Fu media expert” and academic scholar of all things relating to Martial Arts genre fiction and Wuxia in general.

And here's the thing about that: I couldn't be anything the least bit further from that, nor have I ever once remotely claimed to be in the first place. Despite how creatively I can string together a sentence or two and despite how long I can drone on and on about a constant, never-ending torrent of trivial bullshit, don't for one second think that I'm anything other than a total fucking dumbass when push comes to shove.

I've known throughout my life a fairly wide, diverse assortment of ACTUAL smart people, who in numerous fields of subject matter, up to and including this one here (Wuxia and ancient Chinese mythological Kung Fu lore) can soundly hand me my fucking ass without even pretending to put forth any effort into it. There's any NUMBER of Wuxia enthusiasts out there who can legitimately lay claim to being actual no-bullshit academic-level experts on the matter and could do what I'm doing now (overviewing just the barebones basics of the genre) whole vast, infinite WORLDS better than I've been doing thus far.

Compared to them, I'm a fucking simpleton. I'm the Beavis and/or Butthead to their Daria (probably more of a Beavis if I had to pick). The aptness of that particular analogy with regards to this topic is actually sort of integral to my own history as a Wuxia/Dragon Ball fan and will be revisited and explored in greater detail later on.

I digress. For now though, let me just apologize dearly to you all for being the “best” that you folks currently have to work with on this for the time being. That in itself is incredibly sad as, as I've said, there's FAR infinitely better knowledgeable scholars of all things Wuxia out there than myself; people who actually know Chinese and can quote you ancient Youxia poetry and literature chapter and verse and relay to you all sorts of incredibly fascinating history on some of the earliest ever incarnations of many of these stories and character-types. My knowledge of the truly ancient, nitty gritty historical Wuxia prose and lit predating the 20th century is nothing if not embarrassingly rudimentary and basic.

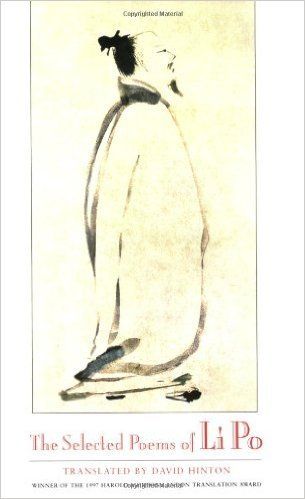

My biggest so-called “bragging rights” in this area is my having struggled my way through a couple of college translations of The Water Margin, Journey to the West, and about 70% of Romance of the Three Kingdoms in elementary school, doing a 6th grade book report on Li Bai...

(From a dog-eared collection of his poetry that I got in a dumpy-ass pawn shop for what couldn't have been more than 5 or 10 bucks)

...reading some online FAQs about a few select untranslated novels and the genre in general back in the early 90s, and watching a few raw, untranslated peking opera performances of a few ancient Wuxia myths on International Channel and a few Hong Kong cinema websites (during the really early days of when RealPlayer and Quicktime were “cutting edge”) in the mid to late 90s with what I can assure you was almost ZERO understanding whatsoever of any of the deeper nuances of the shows.

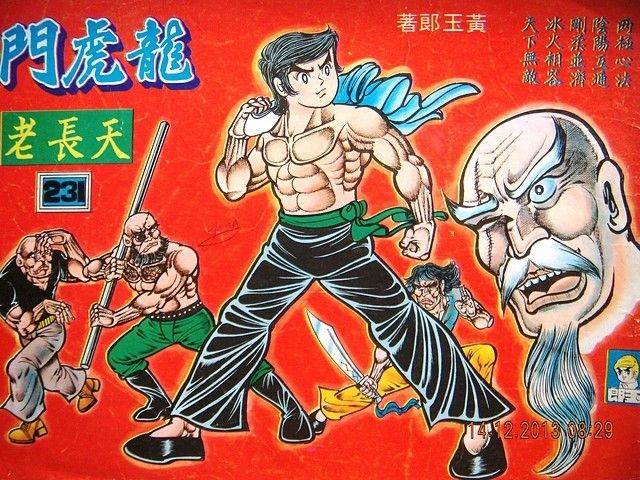

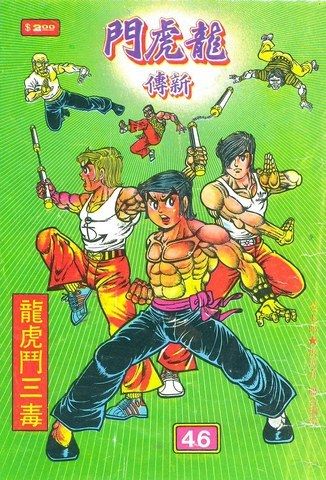

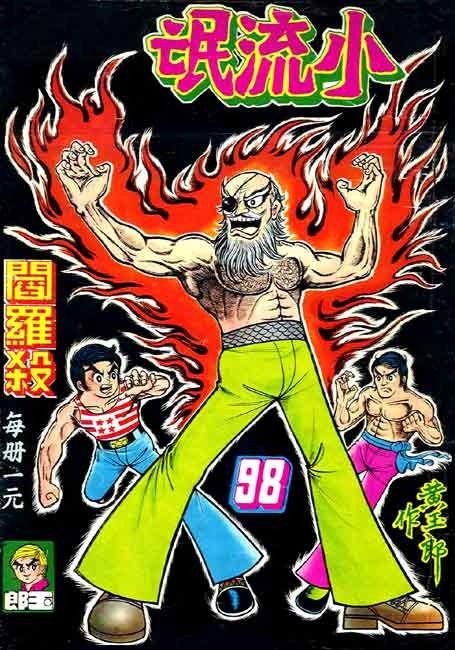

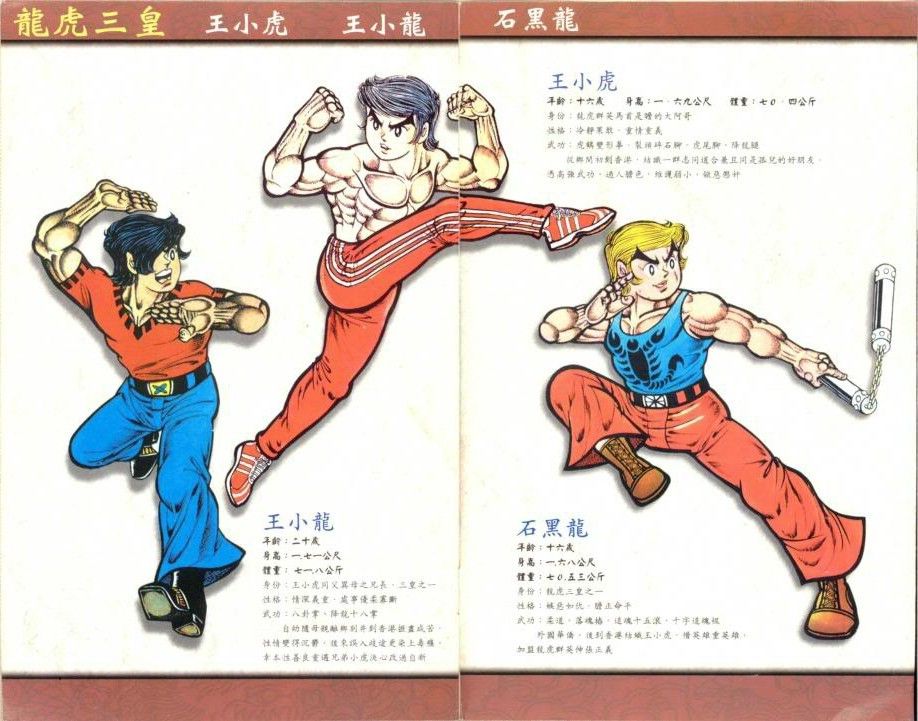

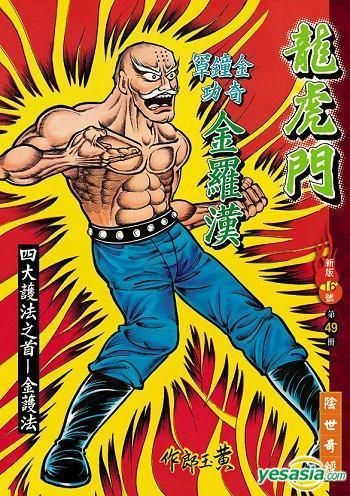

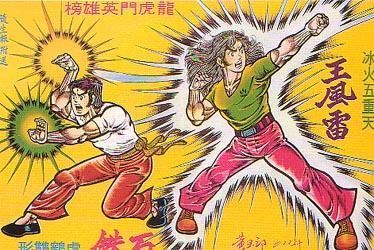

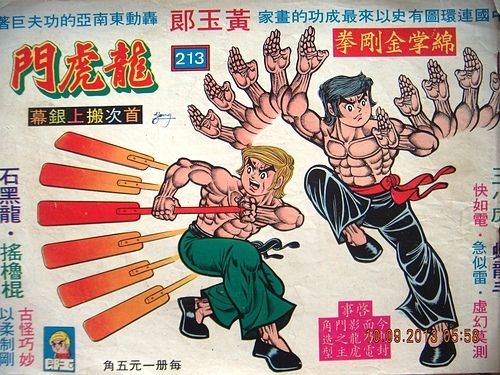

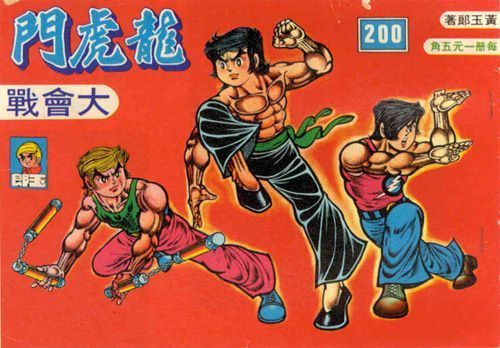

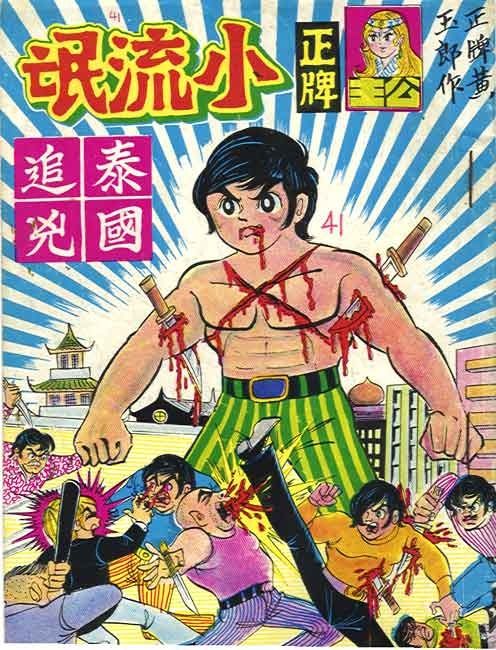

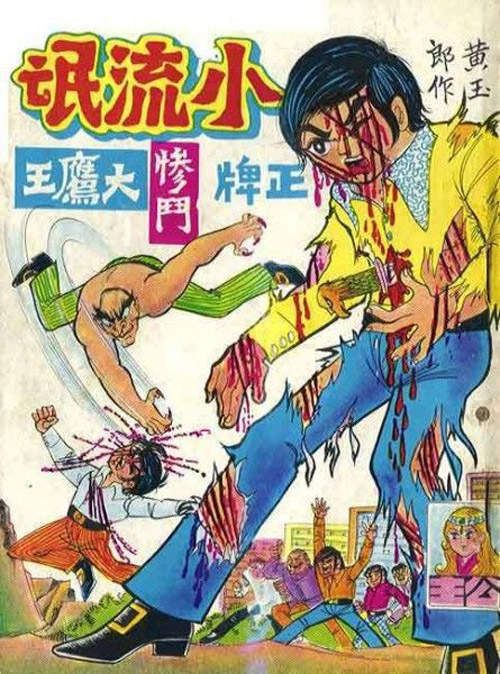

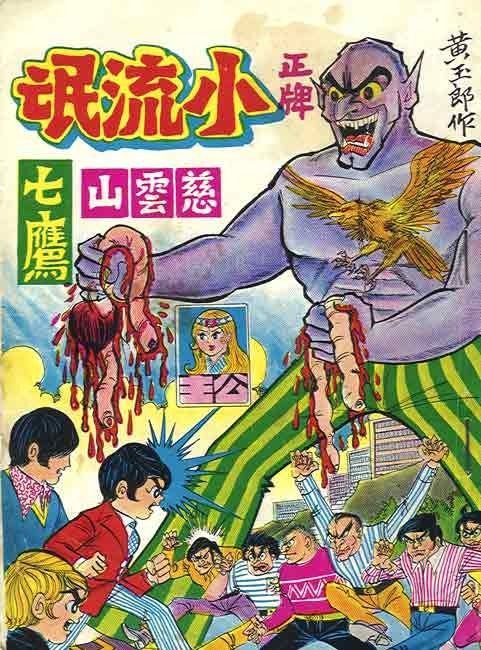

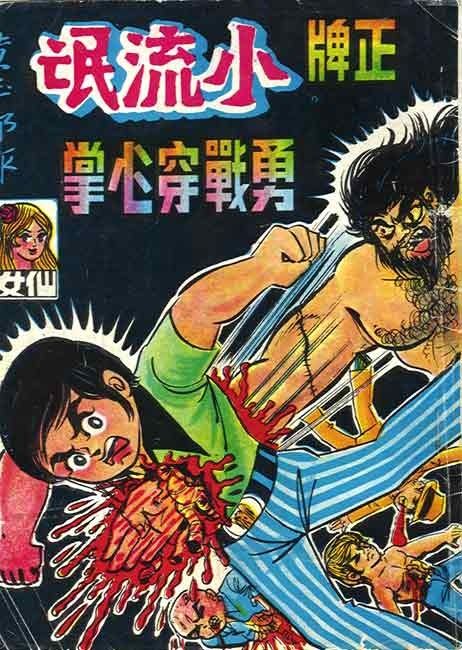

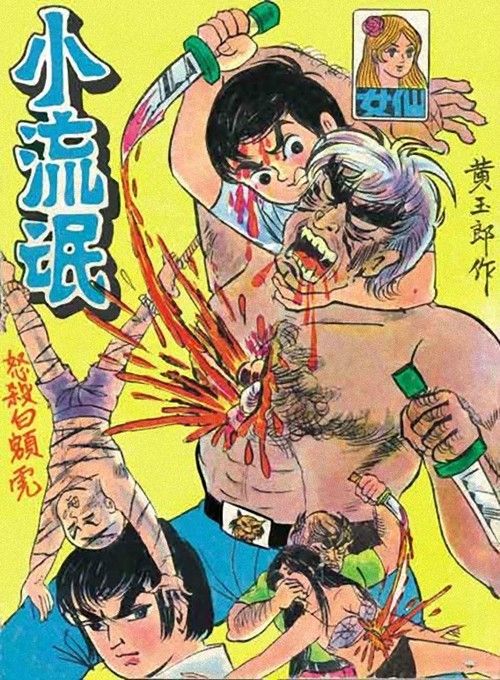

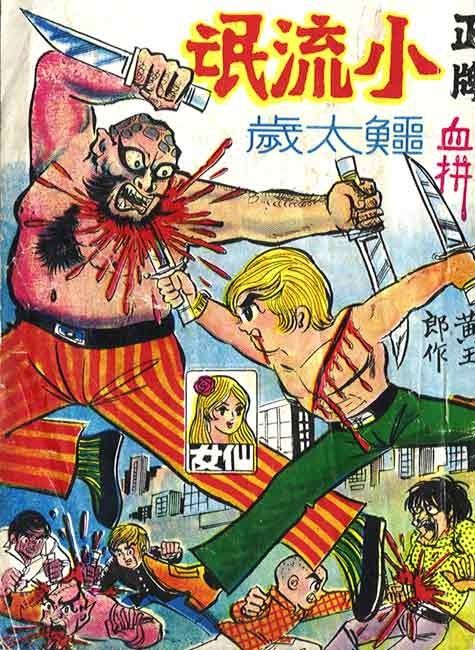

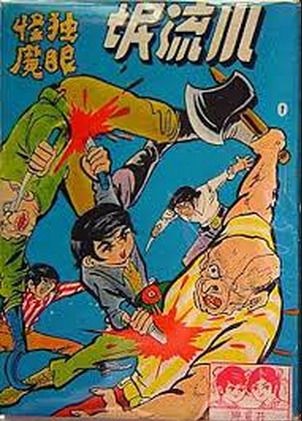

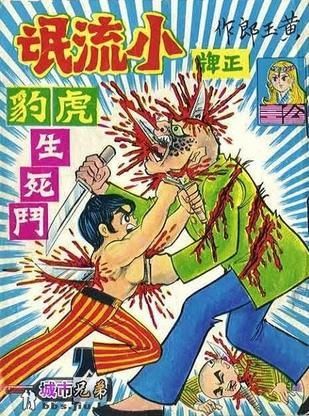

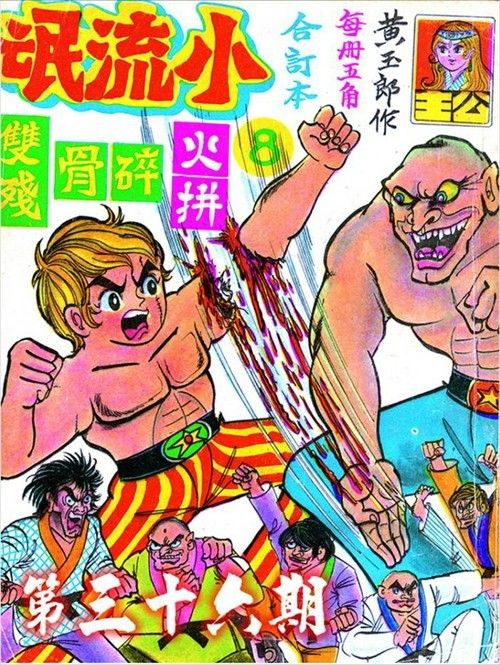

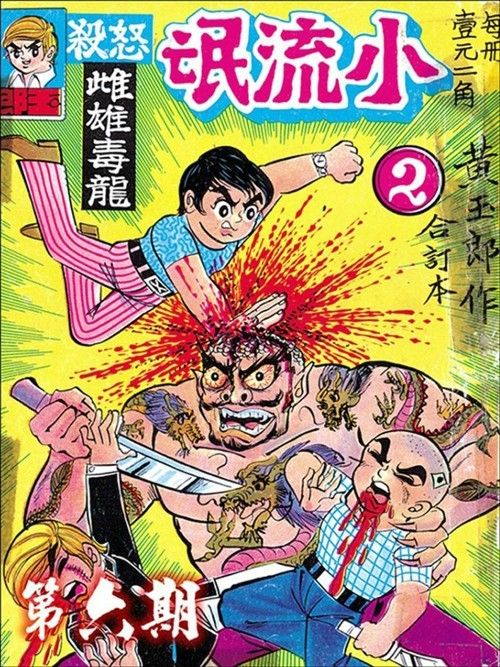

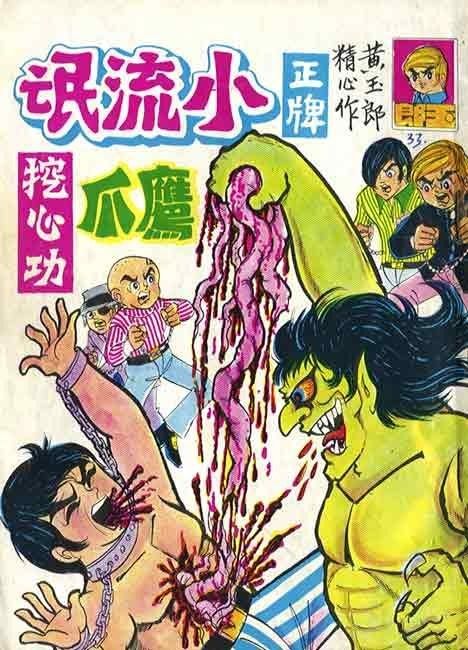

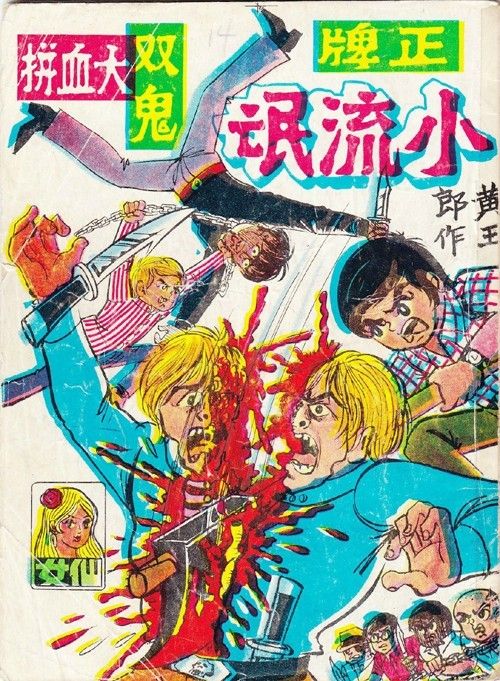

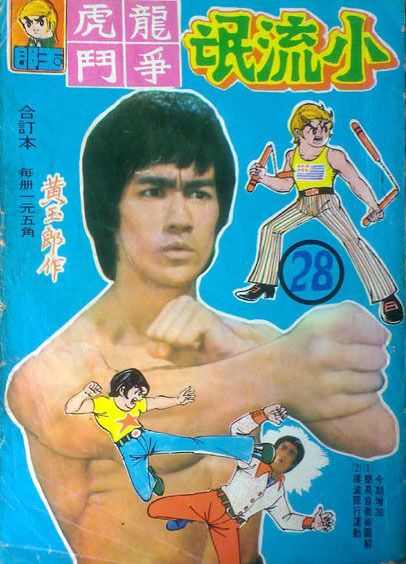

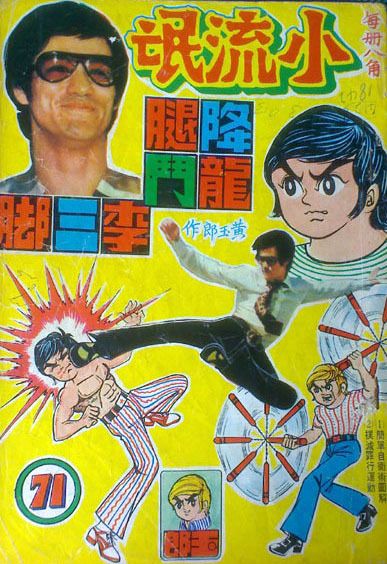

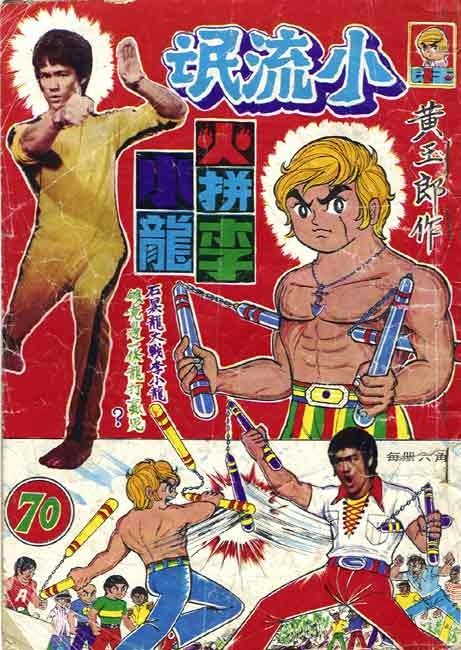

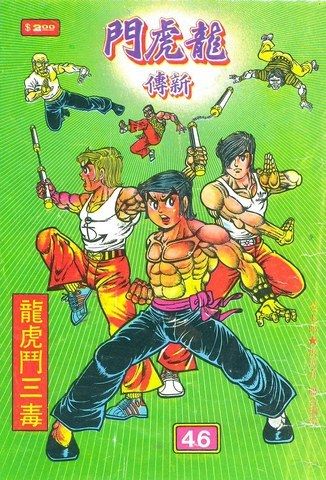

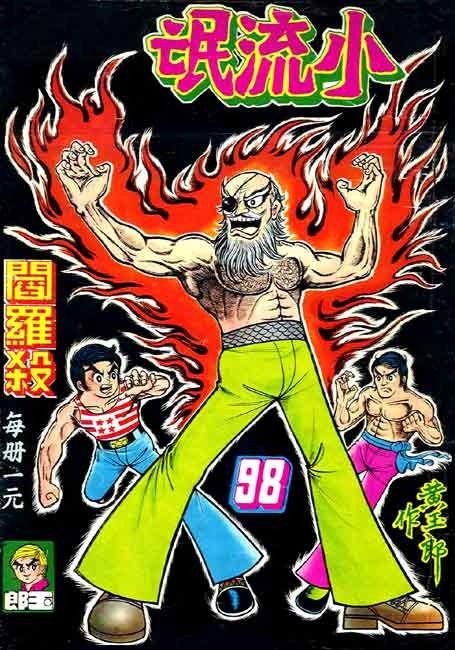

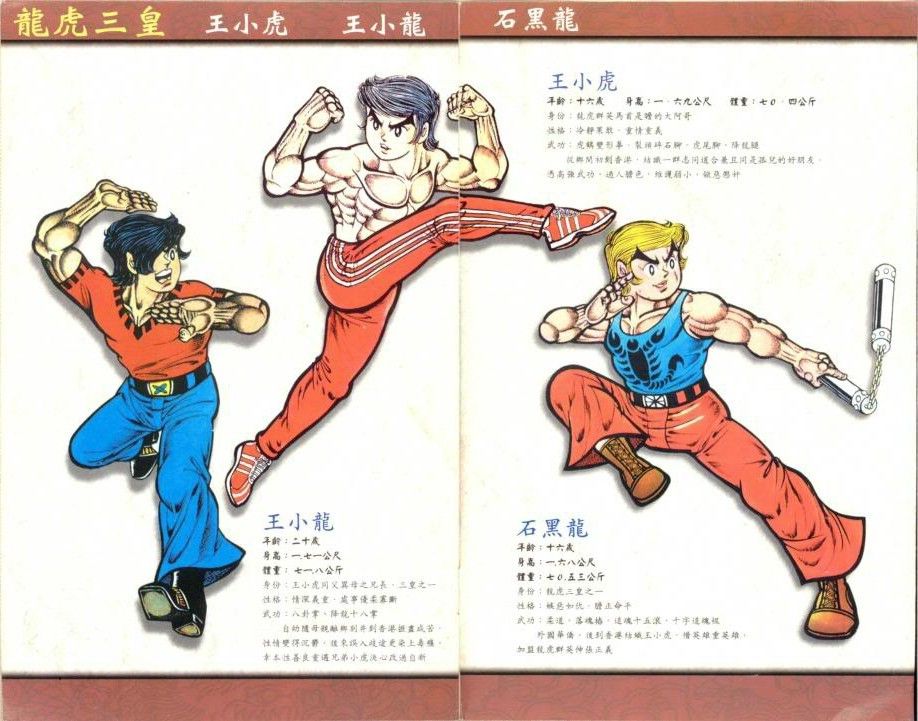

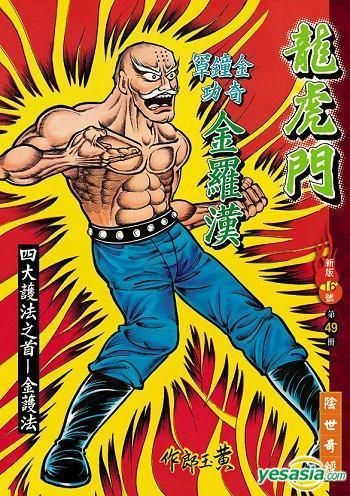

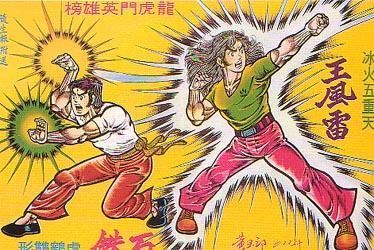

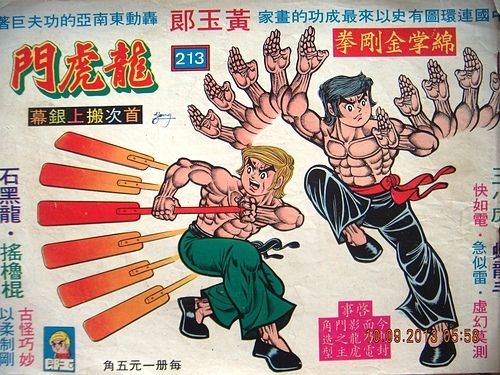

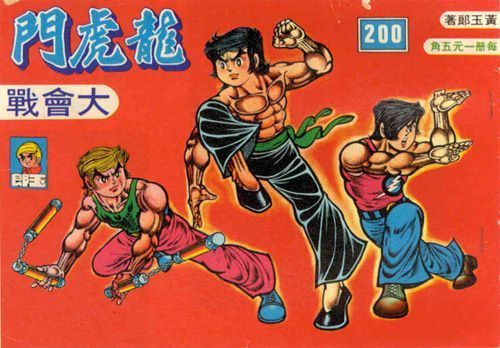

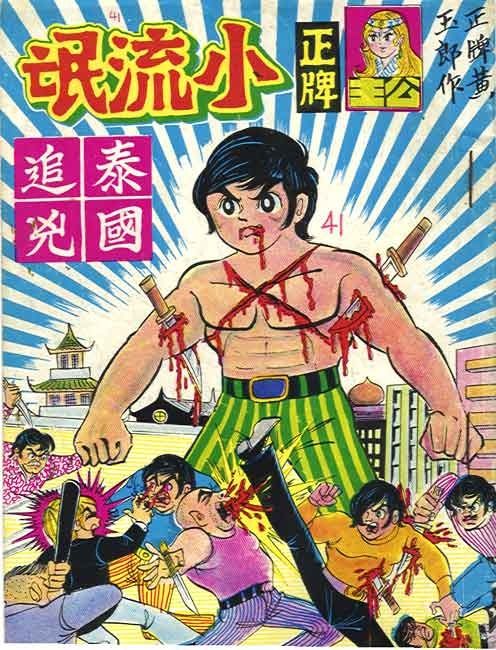

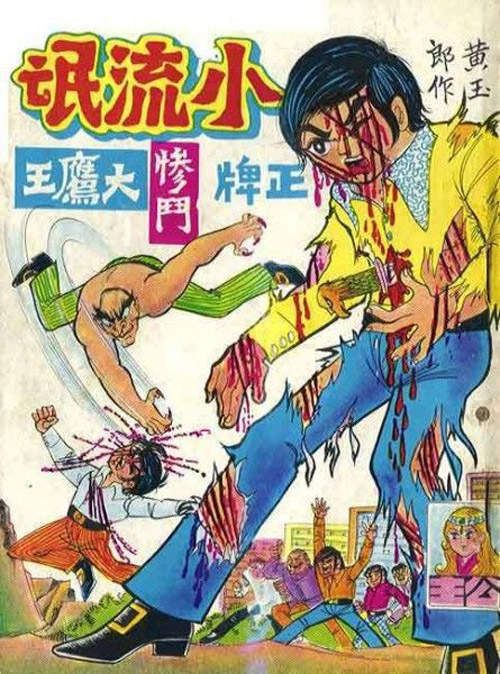

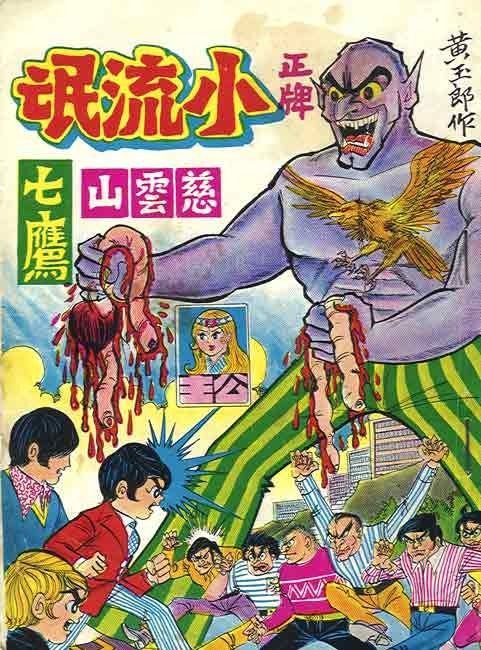

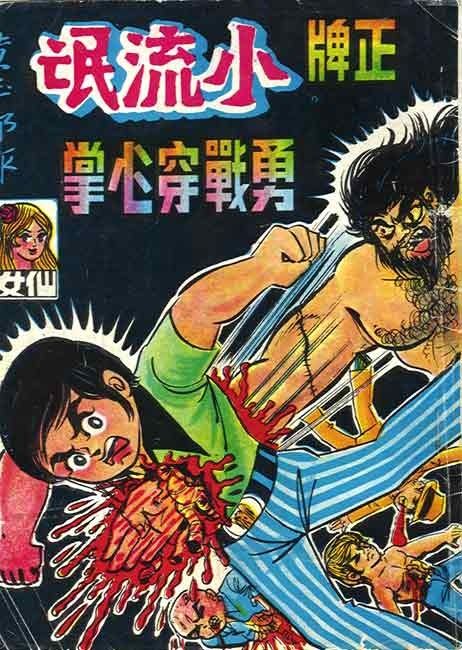

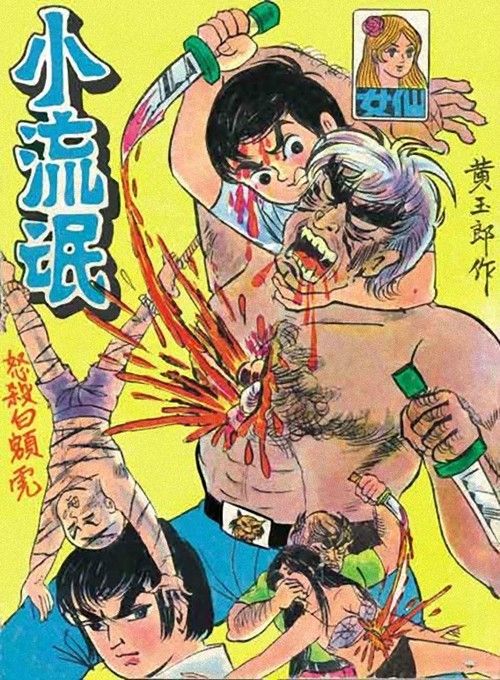

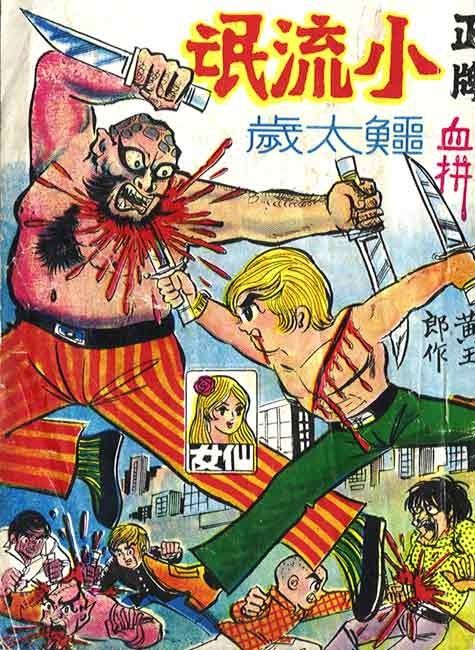

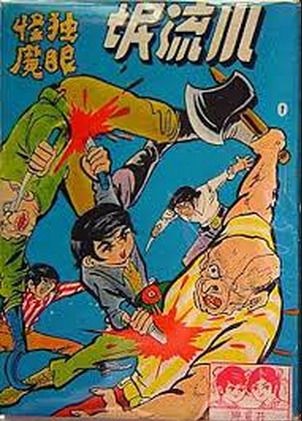

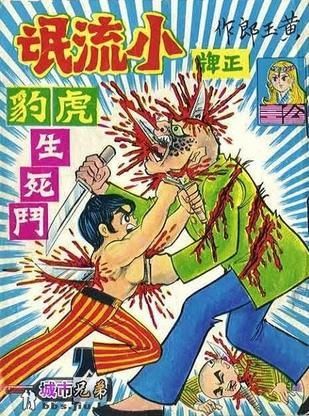

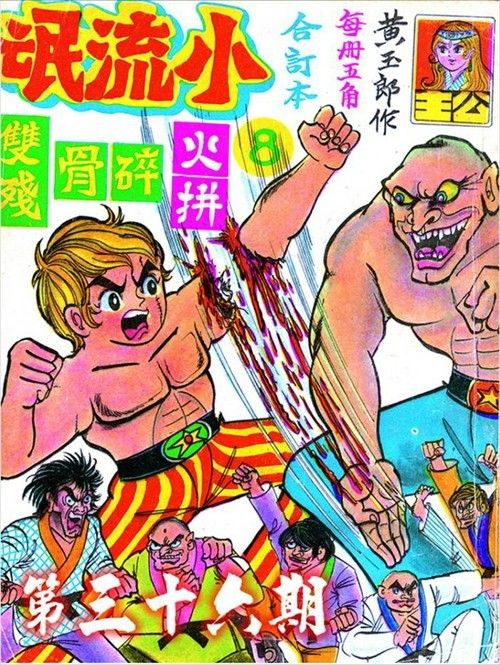

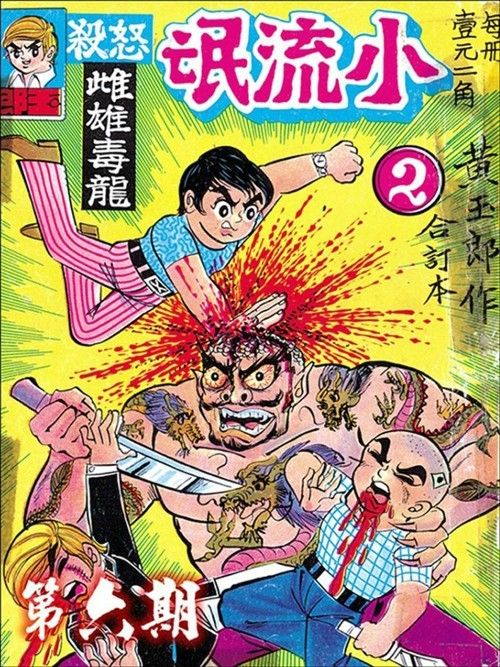

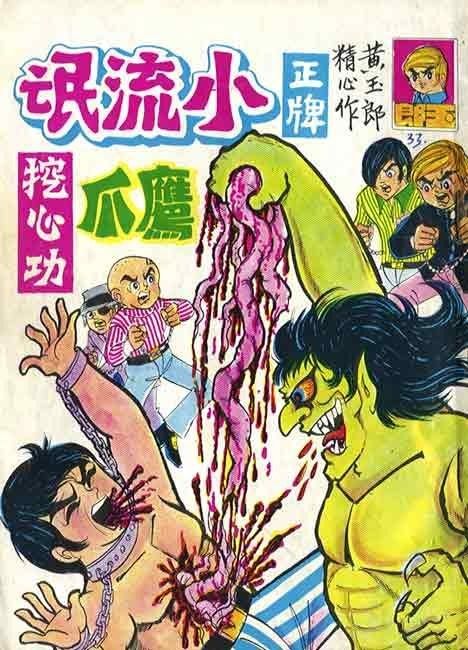

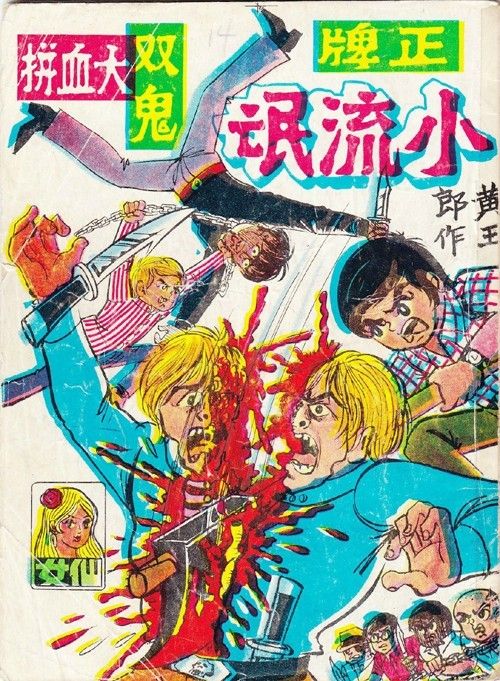

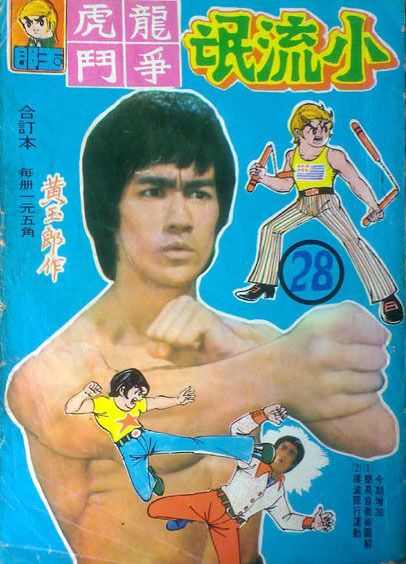

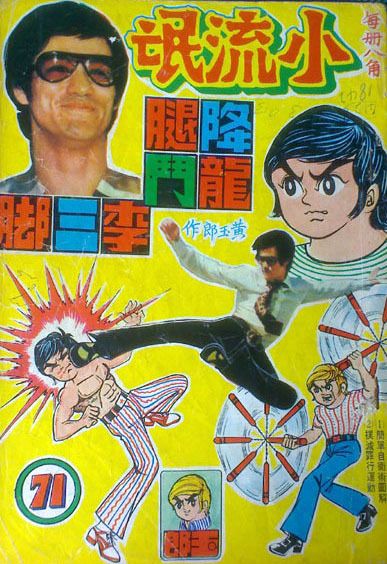

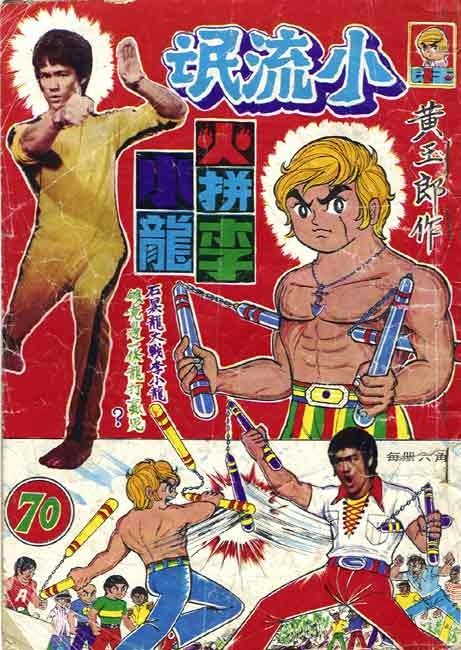

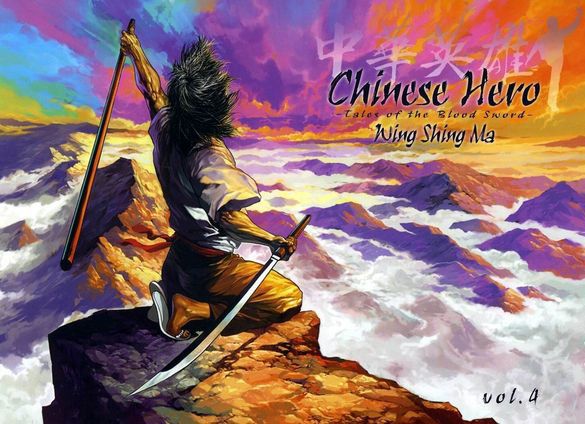

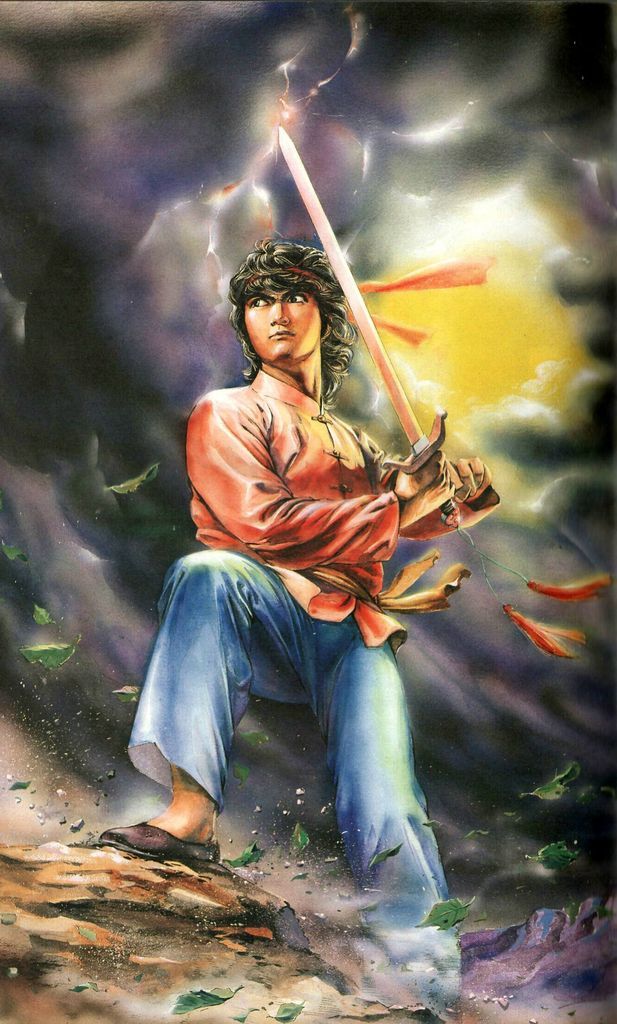

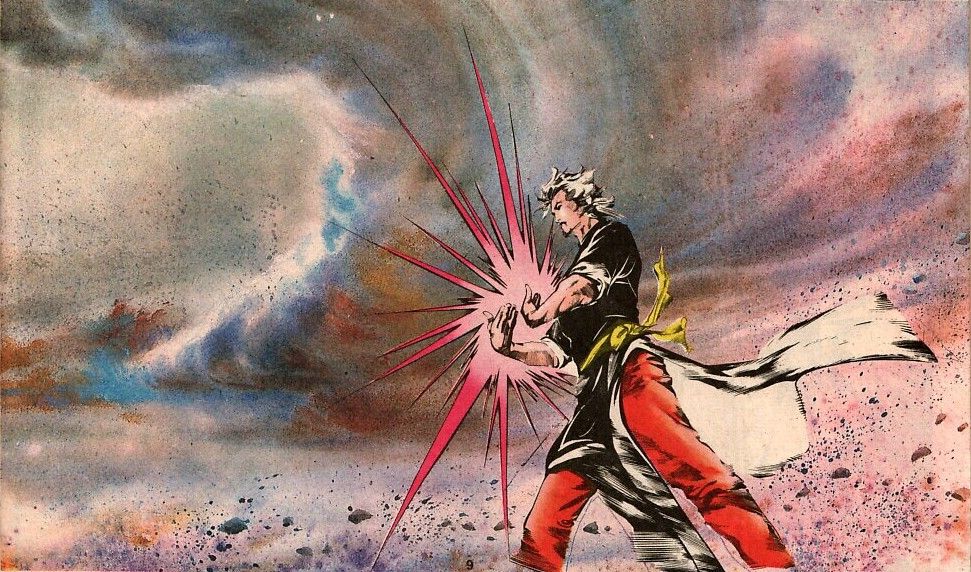

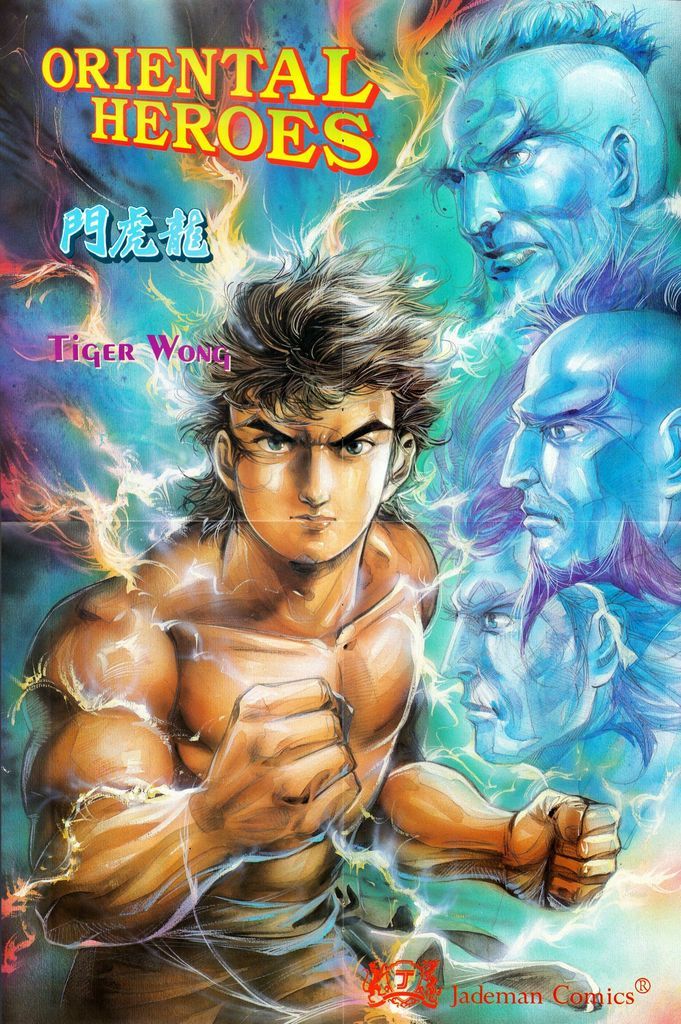

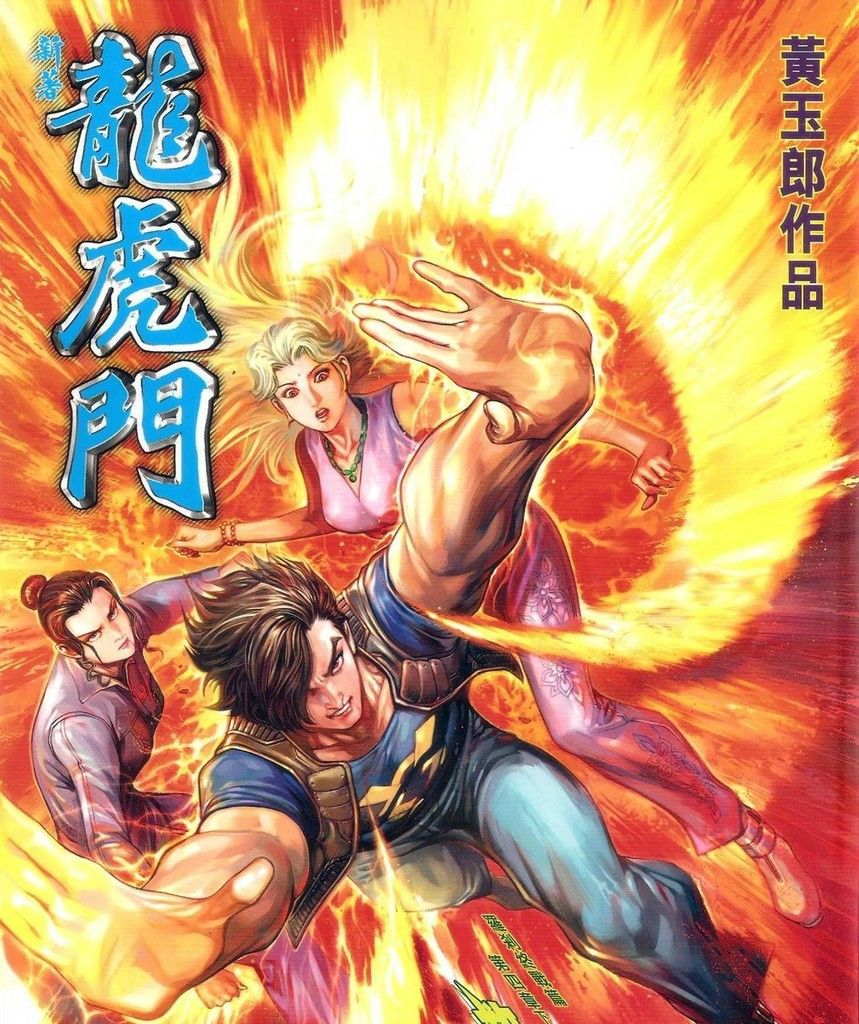

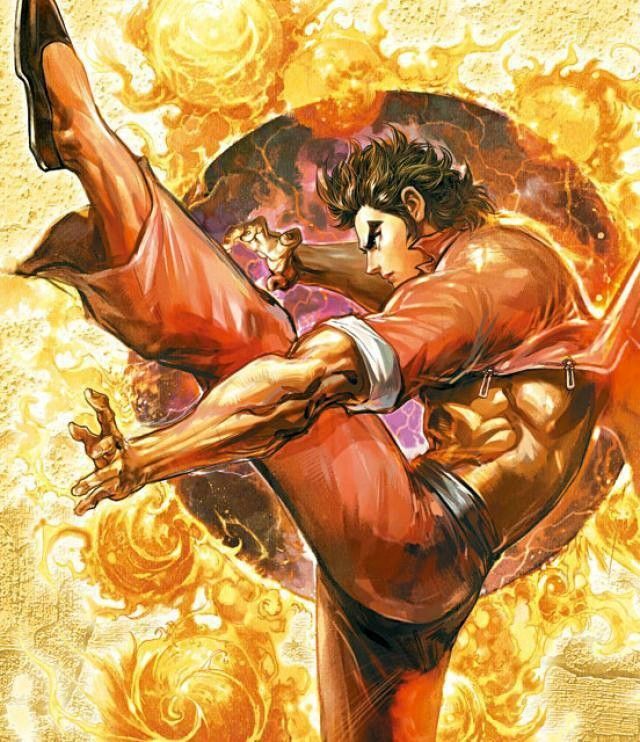

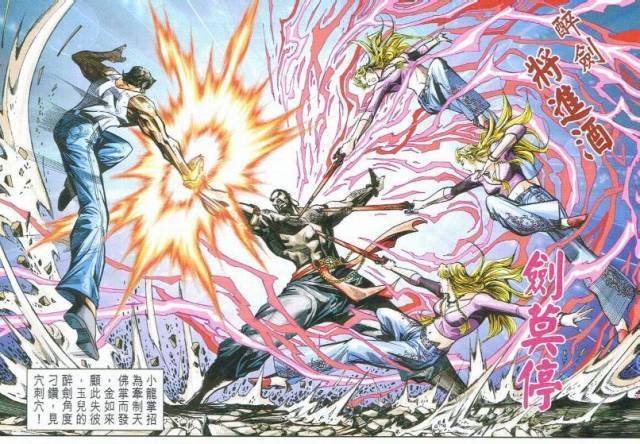

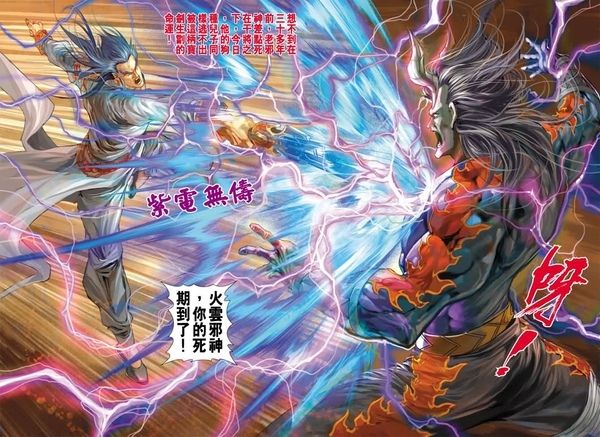

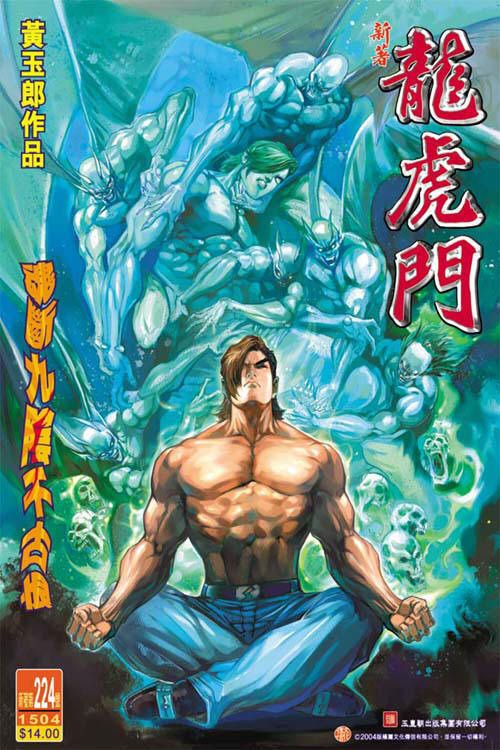

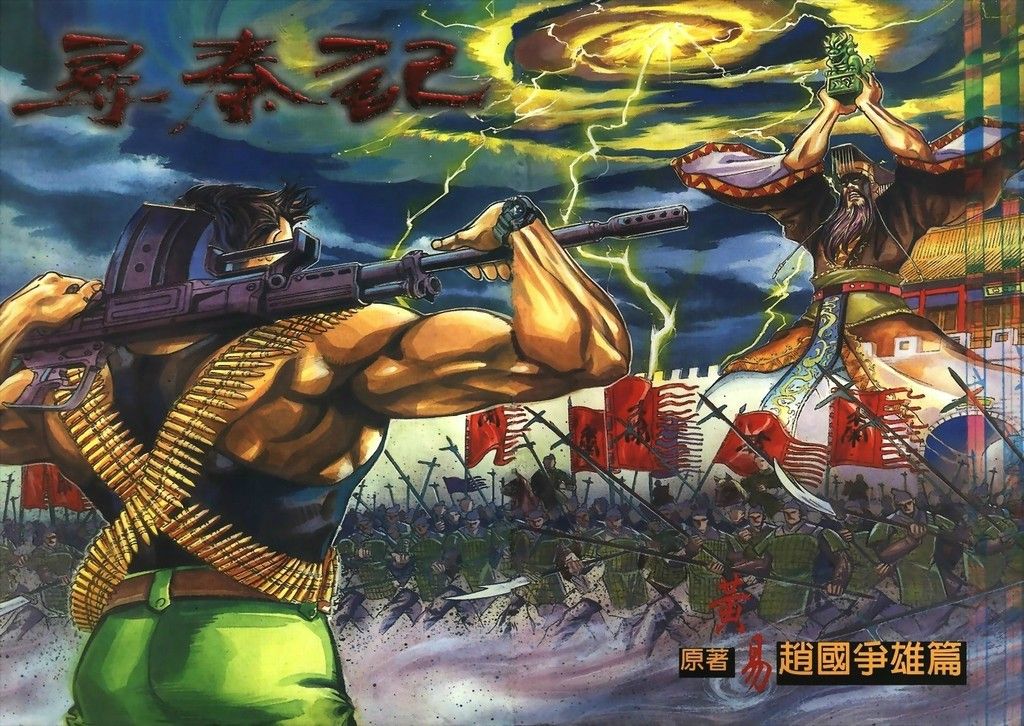

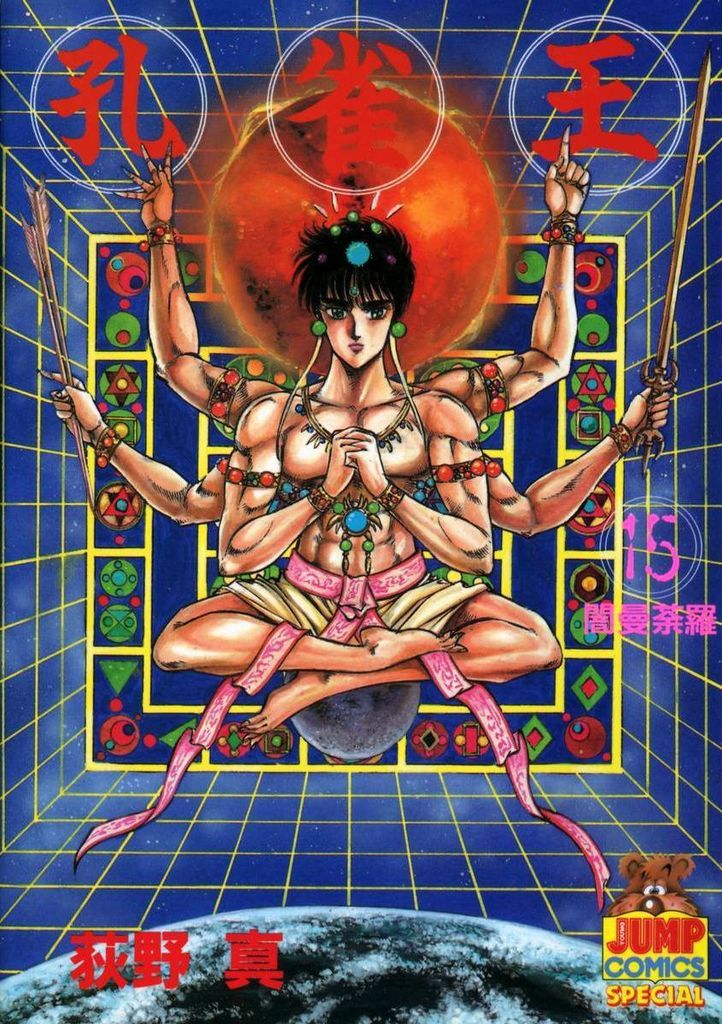

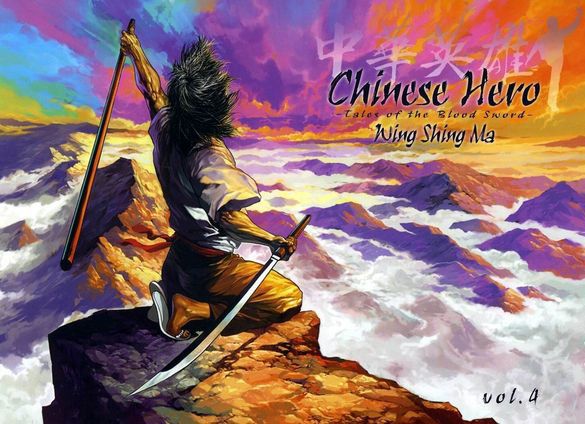

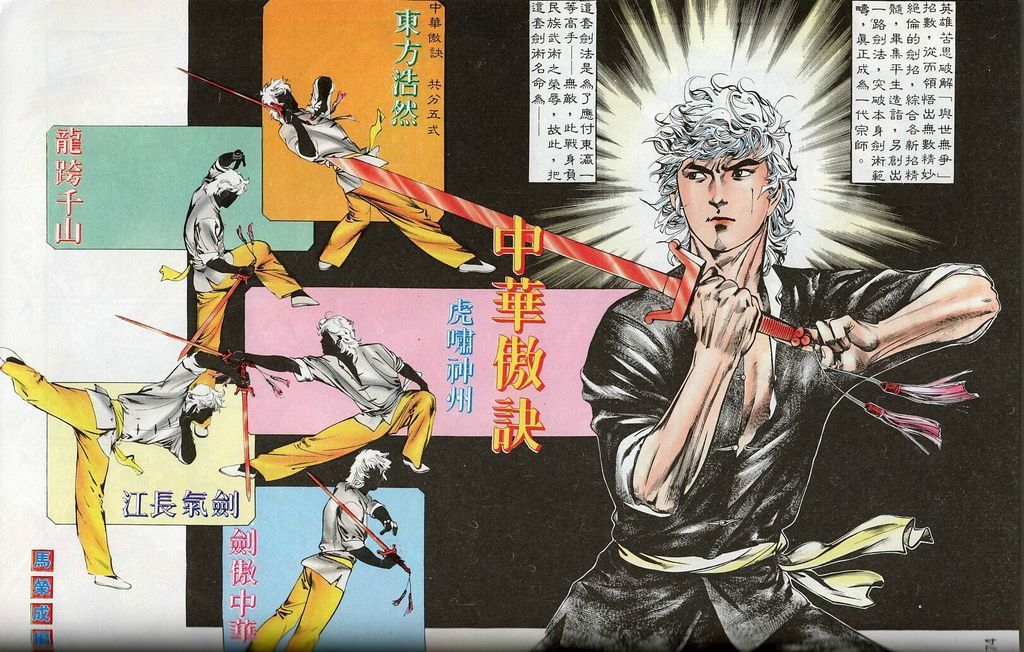

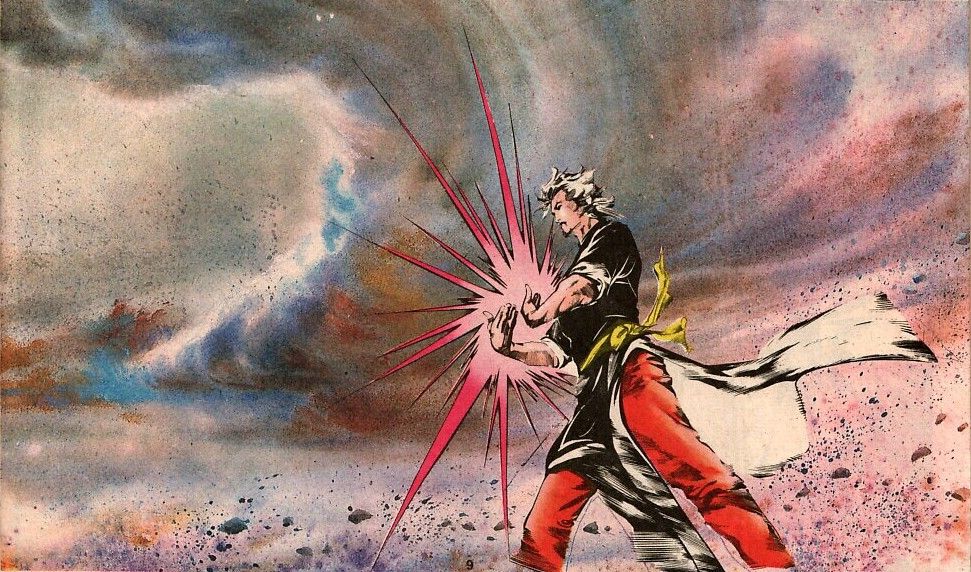

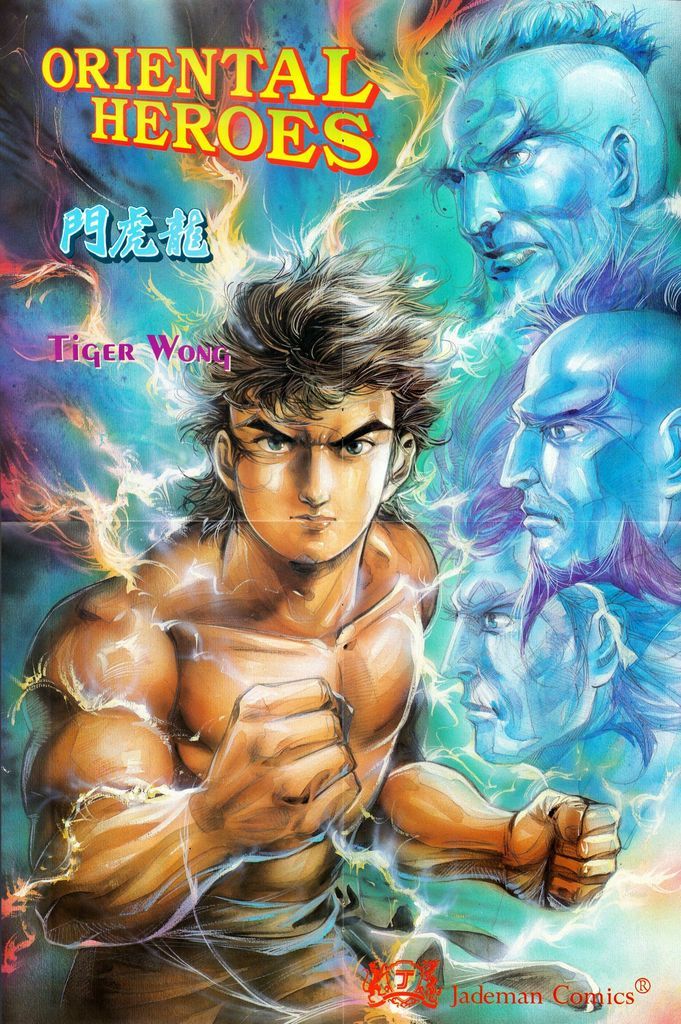

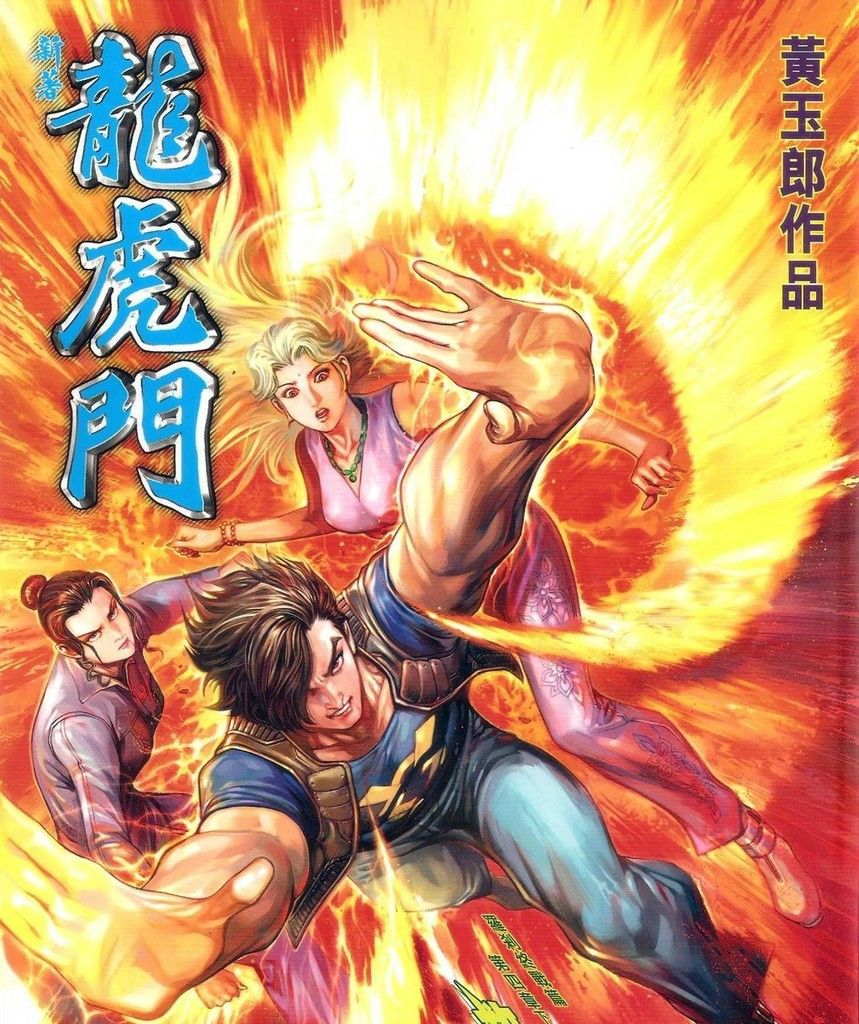

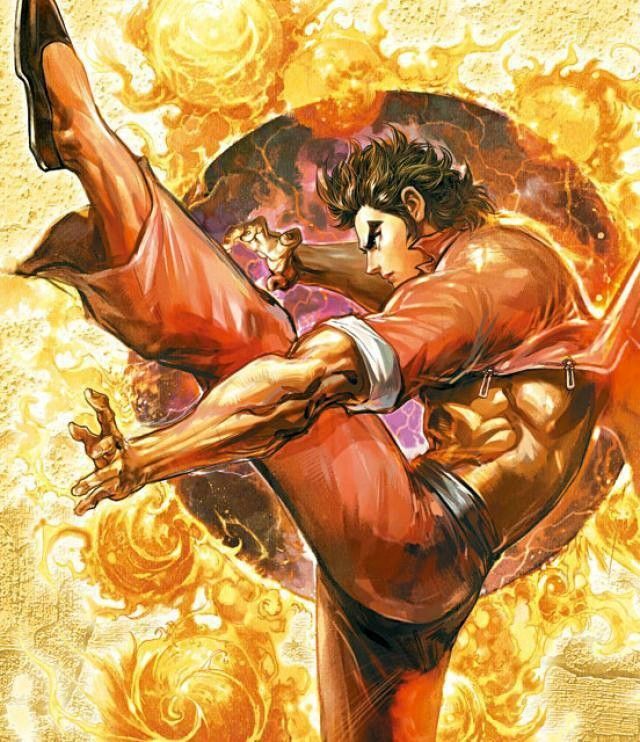

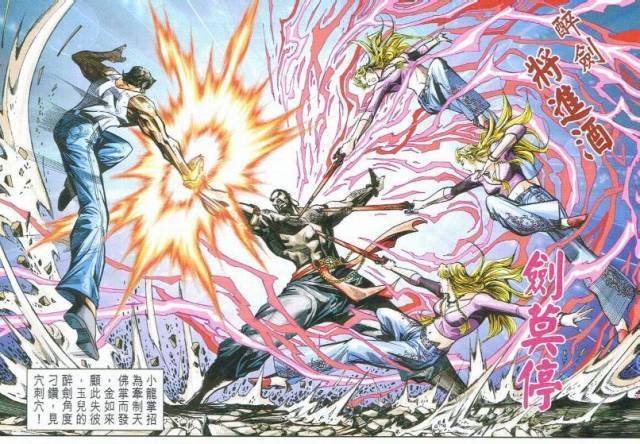

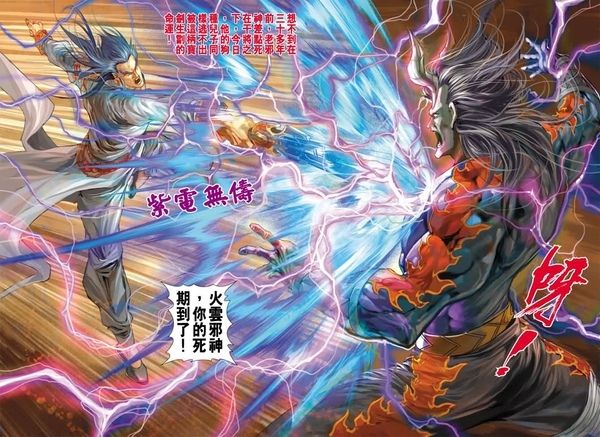

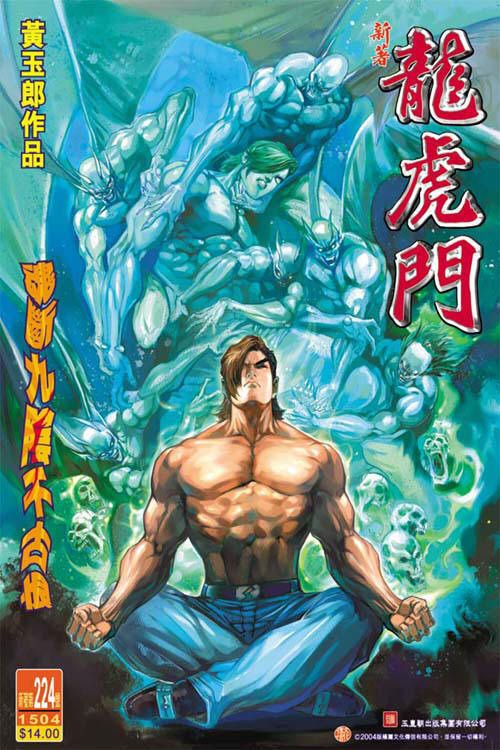

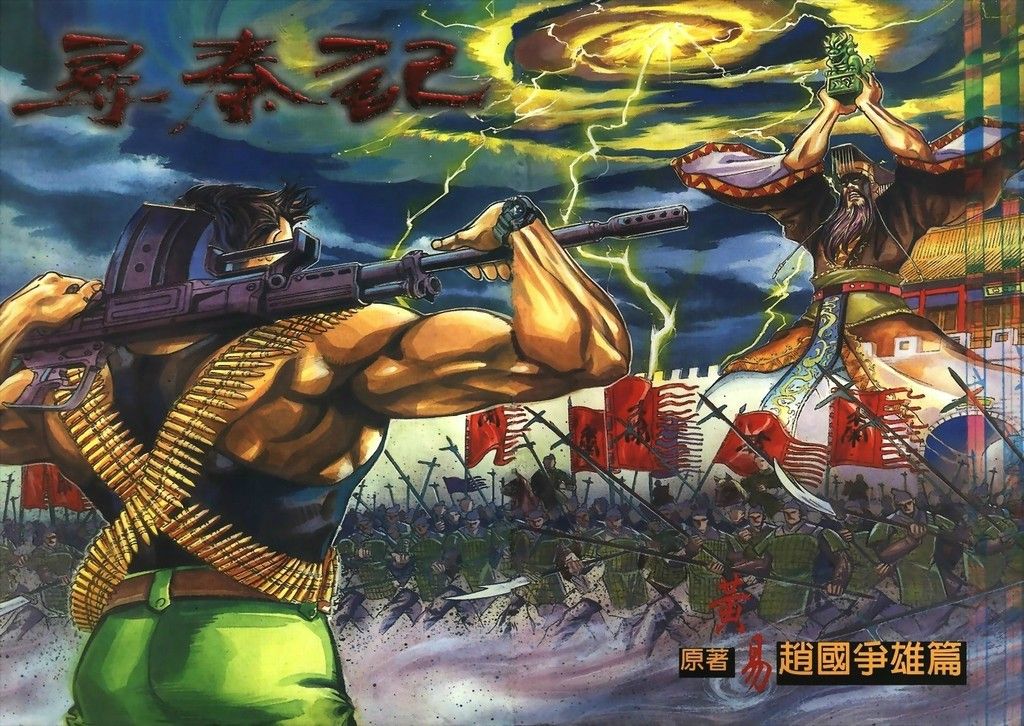

Voila, there, that's almost the entire length and breadth of my “academic/classical/historic” Wuxia expertise. Largely everything else I've known about it my whole life has been divined almost exclusively from a steady diet of Chinese comic books (aka Manhua), video games, bootleg VHS tapes of ungodly countless films, and access to International Channel back in the 90s (which played marathons of various live action Wuxia TV shows every single weekday afternoon, almost exclusively raw and unsubbed). Fucking pathetic.

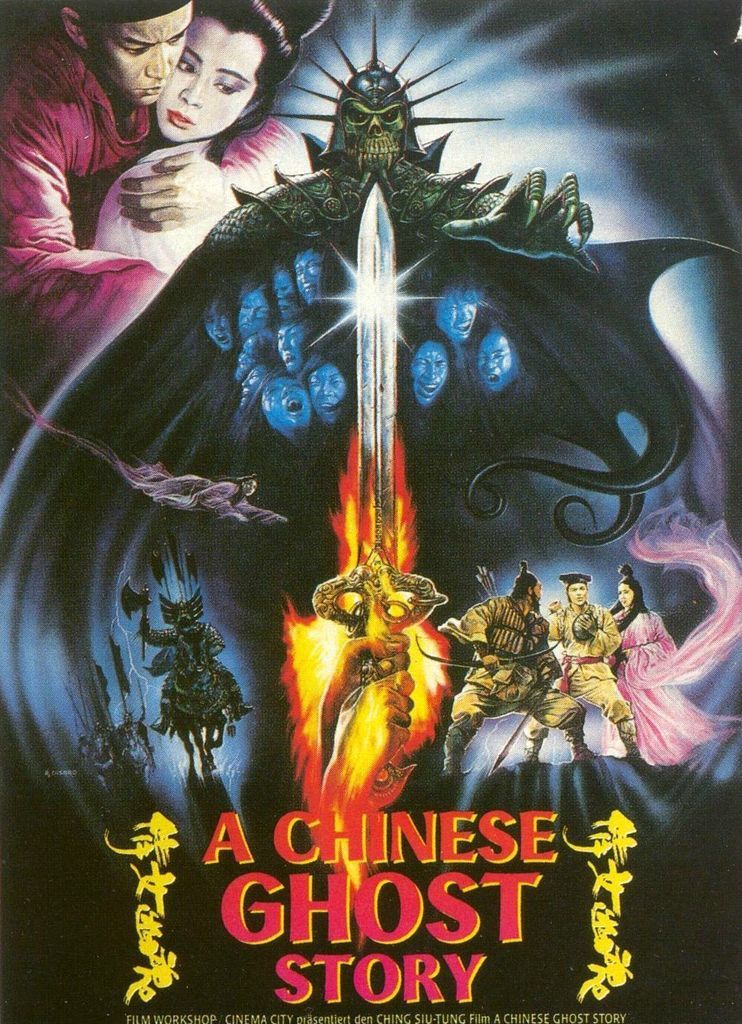

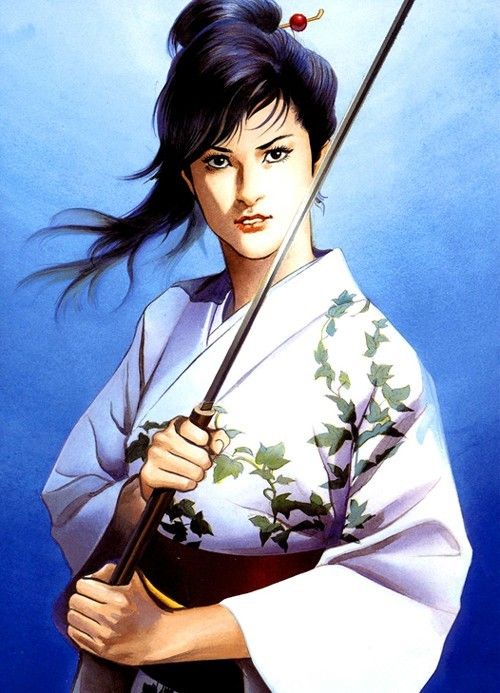

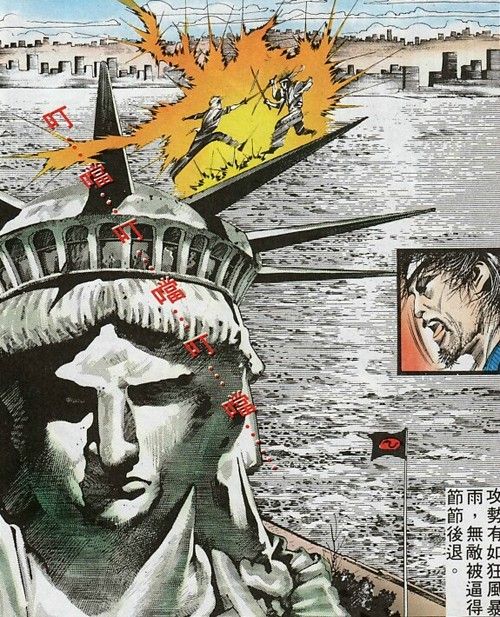

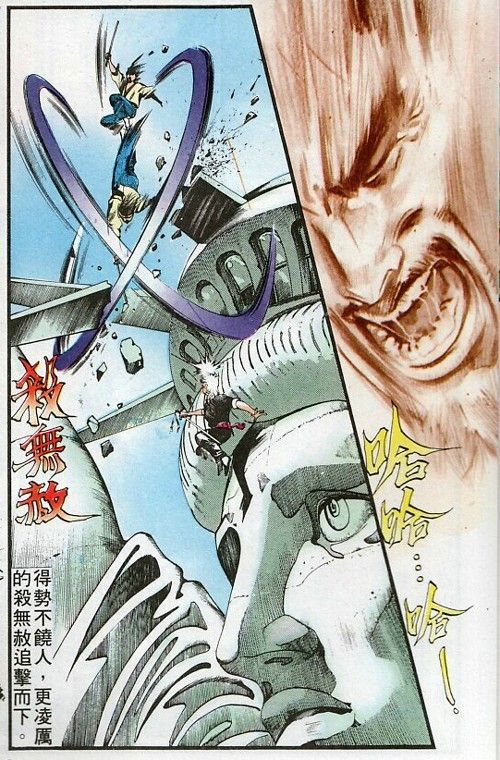

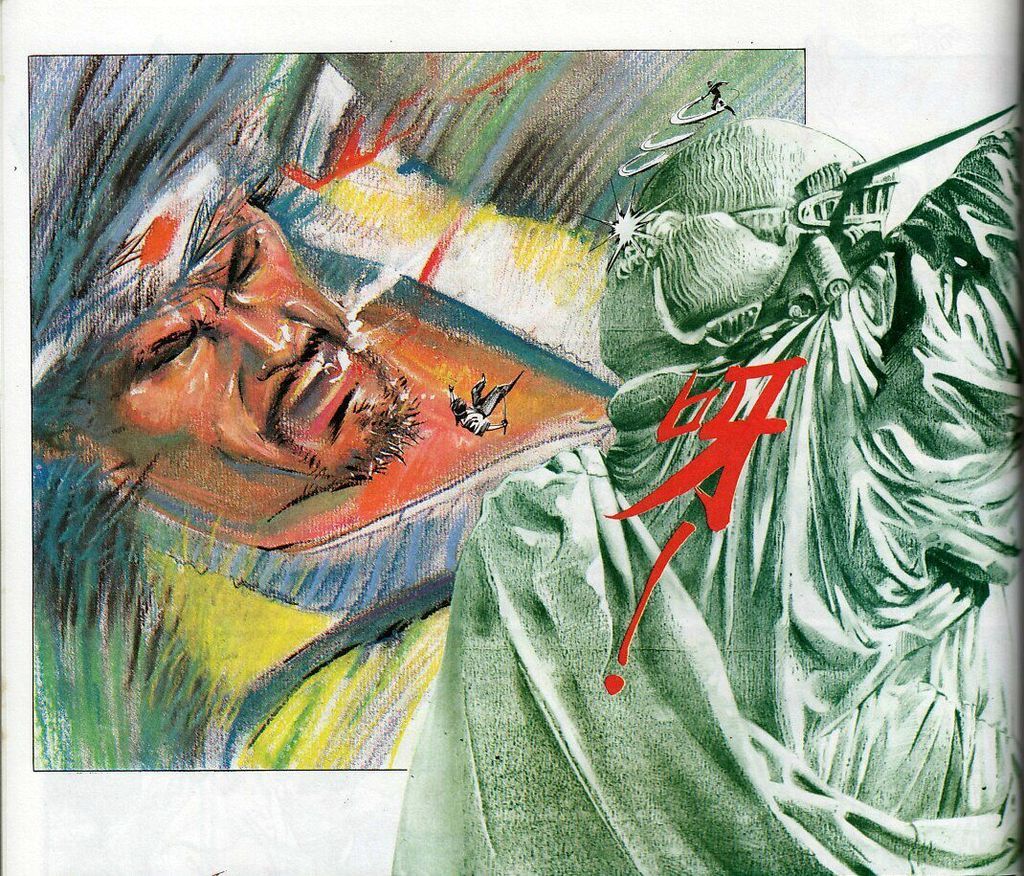

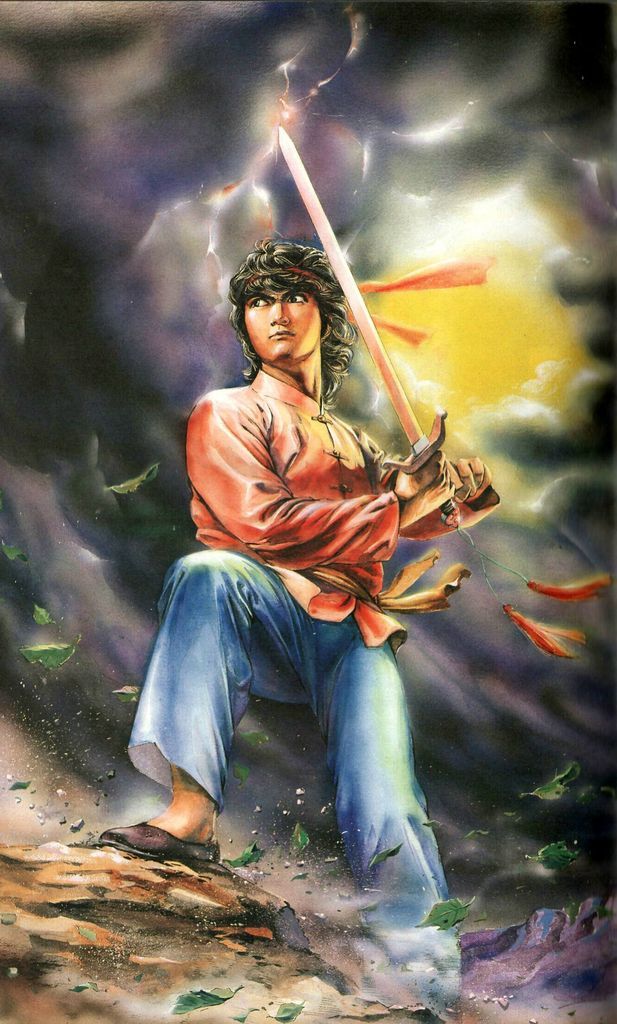

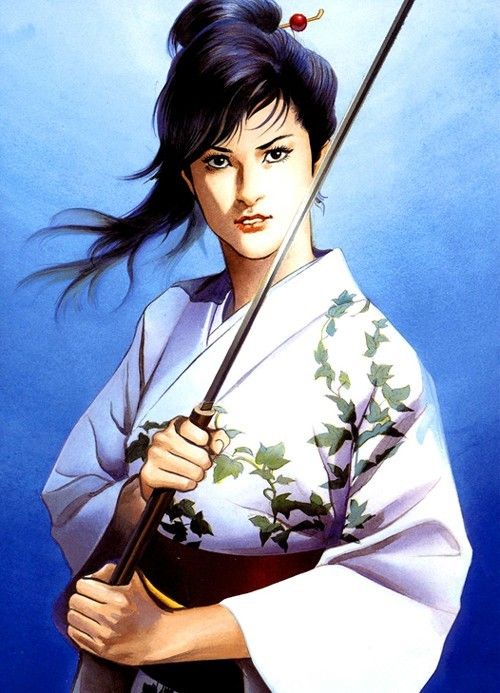

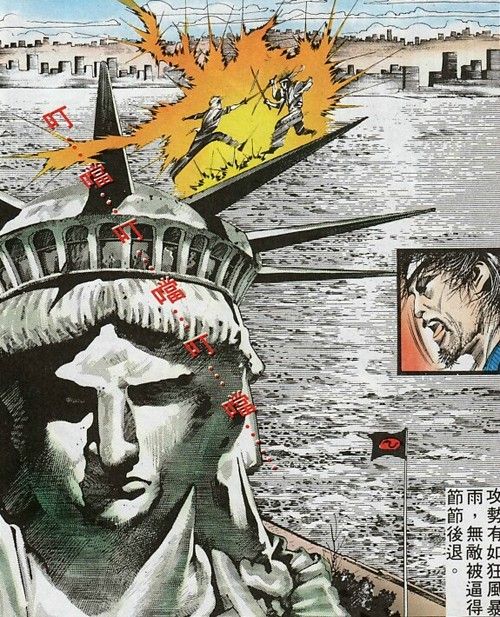

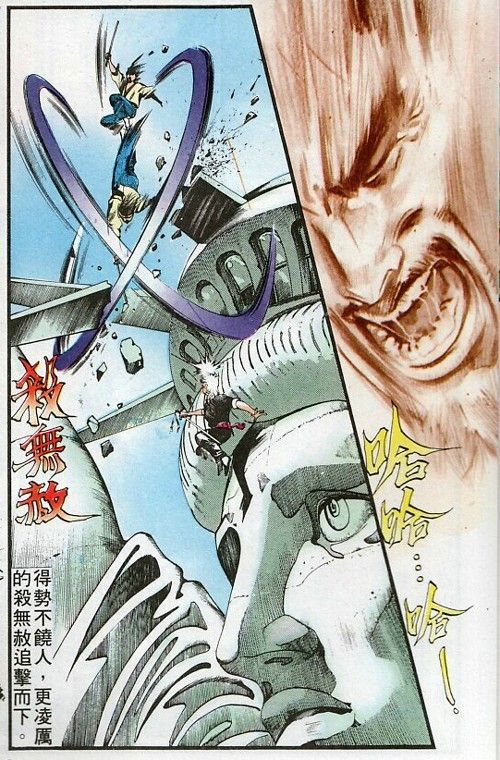

Rest assured I am but an extremely, painfully average fanboy of this stuff, bred largely on the film and comic book output of the genre in the late 80s/early 90s (me being if nothing else a massive creature/product of the late 80s/early90s), as the vast overwhelming majority of my selection of example images and gifs will certainly attest.

And its with that in mind, that we'll be moving away from any laughably piddling attempts on my part of tackling the truly ancient, historical background of the genre and focus firmly on its contemporary media history... with a particular emphasis on film.

Since this whole section is essentially going be a nerd history lesson, this is without question going to be the overwhelmingly largest, densest portion of this entire massive info dump: so its probably best that it be broken up into a few sub-sections for the benefit of clarity and everyone's sanity.

Wuxia in Modern Media Section I: The Classic Years (1929 - 1970)

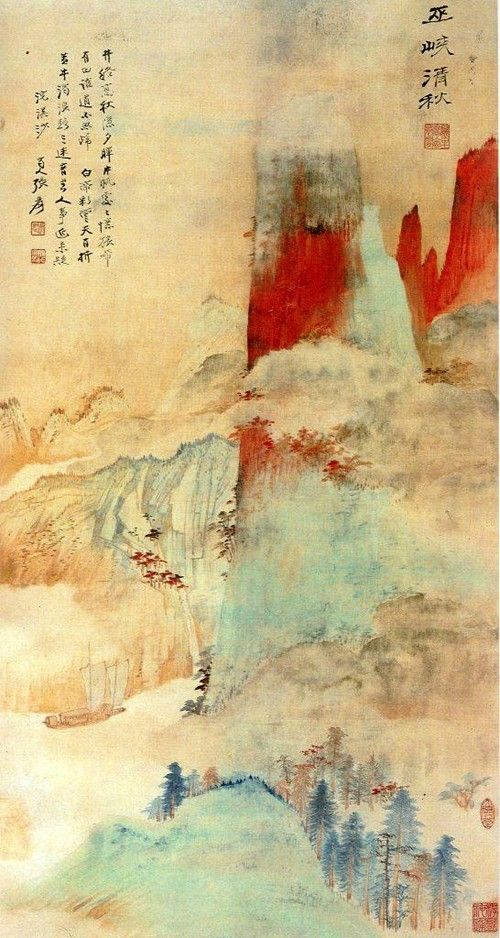

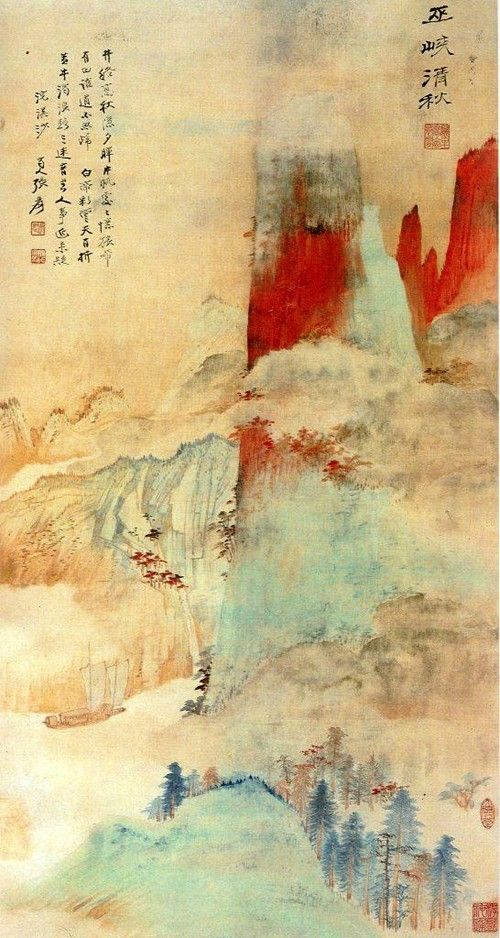

Considering Wuxia's immense cultural importance and near-universal, unceasingly bottomless popularity in its native China almost all throughout its history, little time was wasted before it made its mark in early 20th century media. Wuxia has been a part of more modern Chinese media and pop culture for almost literally as long as the existence of film itself.

That's right kids, that means that Wuxia was also very much around for the era of Silent Film and Film Serials.

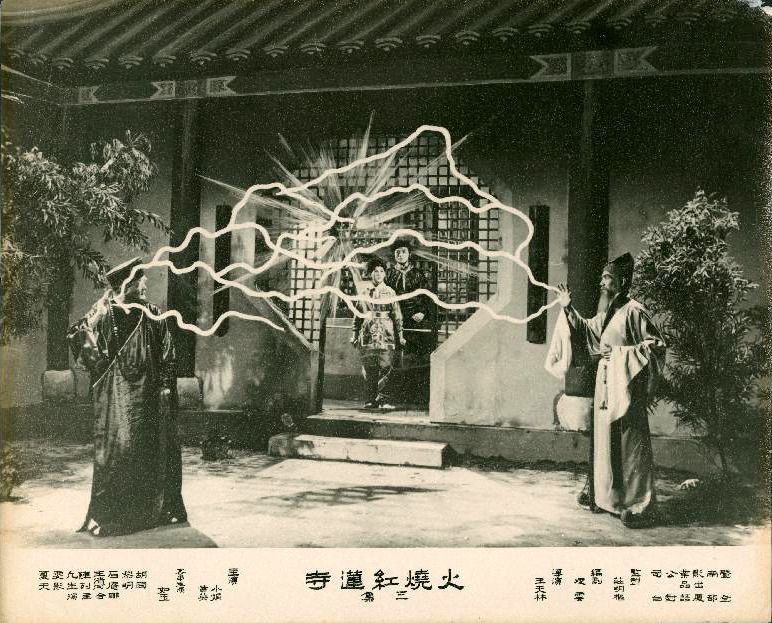

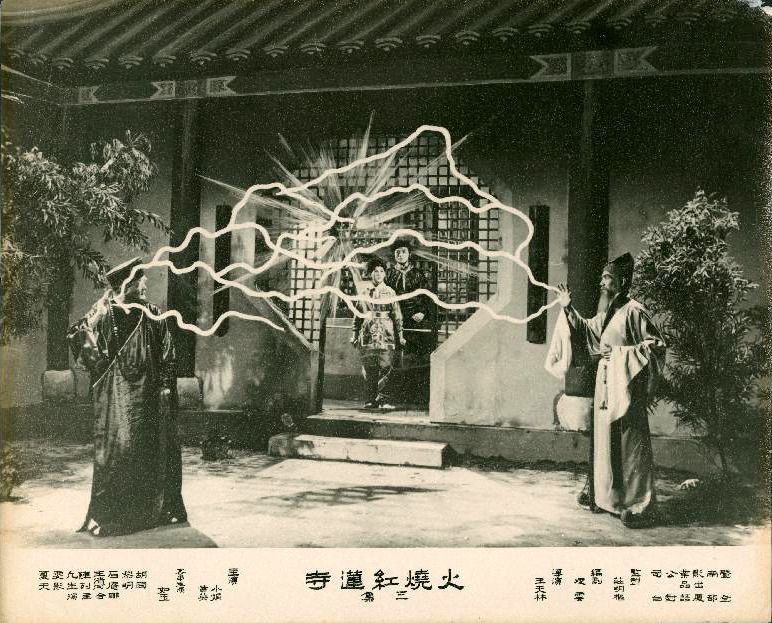

Pictured above is a still from The Burning of the Red Lotus Temple, one of the earliest Wuxia films... possibly THE first ever Wuxia film (making Wuxia a fairly late genre entry in the history of silent film). A serial released in a massive 16 installments from 1928 to 1931 and adapted from a newspaper strip (told you this genre invaded literally EVERY form of storytelling in existence), it tells the story of a long, daring rescue of a martial arts master by his devoted students from a large temple filled with hidden enemies, traps, and other dangers.

The temple in question of course is the infamous Red Lotus Temple, a hideout for cutthroat criminals who's MO is masquerading as benevolent Monks (the Red Lotus Temple would make return appearances in a great many more Wuxia films and stories over the ensuing decades, even up through the 90s).

The influence of this film upon the rest of the genre across the rest of the 20th century and beyond absolutely cannot be overstated. This film essentially laid the basic groundwork for virtually EVERY wuxia film that would ever follow in its wake, from its pacing, setpieces, visual effects language, character dynamics and countless other storytelling tics...

…so of course, like so very, very many other early films of the Silent era, it remains tragically lost to time and is presently all but impossible to see anywhere with no known prints currently located. All that remains are still images and various scattered pieces of information and apocryphal trivia from various interviews, historical accounts, and production notes.

Another notable early Silent Wuxia film that DOES still exist however is 1929's Red Heroine. Telling a very standard, rote murder-training-revenge arc (that would of course become an all too familiar stock cliché in this genre), the titular Red Heroine is a young peasant girl named Yun Ko (played by then-popular Chinese actress Fan Xuepeng, who would become in the wake of this film one of the first ever Wuxia stars) who begins the film an average innocent young lady whose village is raided and sacked by a corrupt warlord general. Her kindly old grandmother ruthlessly murdered in the attack and her hapless scholar cousin unable to protect them, Yun Ko is captured and taken to the general's fortress to be made a sex slave in his harem.

Before she can be violated by the general's men however, she's rescued and taken away by an old hermetic (read: Xian) monk by the name of White Monkey who of course is also a great Wulin martial arts master. White Monkey takes Yun Ko under his wing as his student and trains her in the supernatural martial arts. By the end of her 3 years of training, Yun Ko is a master fighter capable of flying, teleporting, and other great feats of superhuman strength, allowing her to return to the general's fortress and wreak bloody revenge upon the evil marauding army.

(Yun Ko soars into battle)

As primitive and rudimentary as most Wuxia of the silent film era may be to modern viewers, these were obviously monumentally popular and groundbreaking films of their time period, bringing to vivid life for the first time ever ancient myth and folklore of Chinese culture only previously imagined in ancient writings, literature, and on the stage.

Indeed stage plays and Chinese opera performances were the closest that Wuxia had to be visualized prior to the advent of film, hence most all of the earliest ever Wuxia films (within and even for some time after the silent era in the early “talkies”) make extensive use of stage performance tricks and choreography for their action sequences, including EXTREMELY rough wirework for flying, puffs of smoke from the ground for “teleporting/materializing”, and hand to hand choreography that is more akin to stylized dancing than visceral combat.

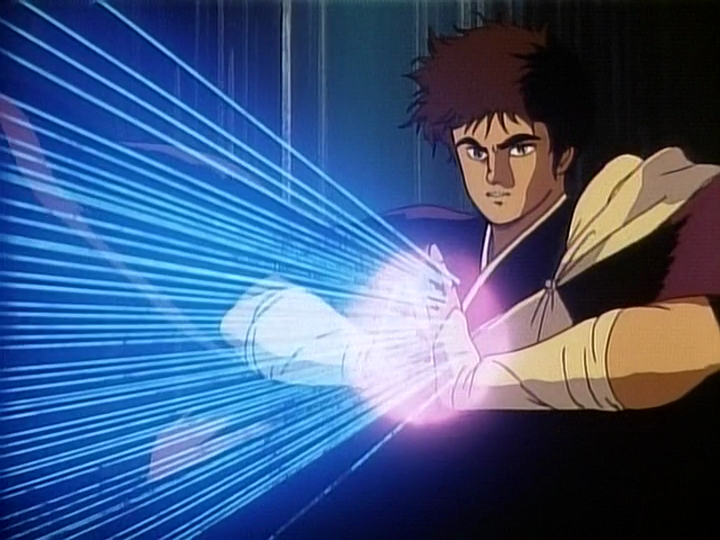

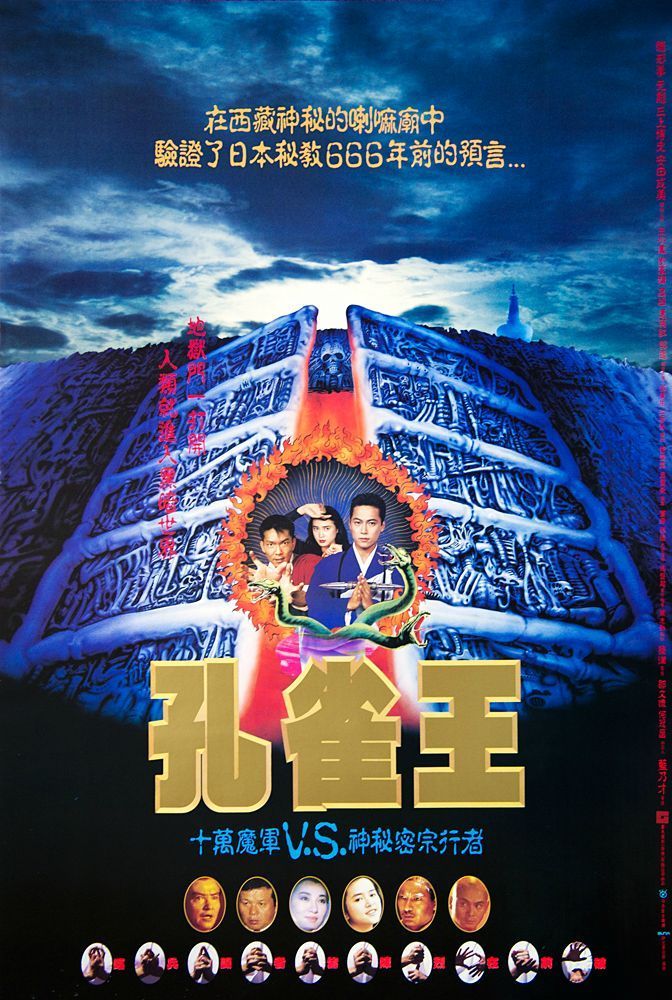

The most cutting edge technological advancement used in the earliest Wuxia films was hand drawn rotoscoped animation for visually represented Ki techniques. These were an absolute marvel to Chinese audiences in the late 1920s when Burning of the Red Lotus Temple first made extensive use of it, and rotoscoping would continue to be the principal means of achieving the effect of Ki auras, blasts, and other assorted magical martial arts trickery throughout much of the entirety of live action Wuxia filmmaking for a great many decades all the way up until the advent and use of CGI became increasingly commonplace during the latter half of the 1990s.

In a serendipitous bit of cultural foreshadowing (which we'll get to the payoff of momentarily) the early silent era Wuxia landscape tended to be an extremely populous-driven film movement, with the genre most loved and consumed by audiences of poorer, lower class backgrounds.

As can be seen just in certain elements of Red Heroine as just one example, there was a hint of lurid pulp and exploitation prevalent in many Wuxia films, along with the general running anti-authoritarian/anti-establishment themes that come with stories focusing on a staunchly individualistic, authority-shirking warrior caste such as the Xia/Youxia, as well as the common Wuxia subtext promoting the individual's accomplishment, talent, and self-improvement over that of collectivist/conformist thinking.

This did not sit too well with the then-first emerging Communist Party of China, who early on saw these sorts of films as threatening, rabble-rousing among the masses, and promoting ideas diametrically opposed to that of Communist principals, making early Wuxia films for some years frequent targets for government raids, confiscation, and banning.

Combined with a general carelessness towards film preservation during the silent era as an overall whole and the easily decaying nature of early film stocks, and it unfortunately makes a GREAT deal of the early silent era of Wuxia films tragically, heartbreakingly lost forever to time, with only a relatively RARE select few films still surviving today.

This hostile attitude towards populist Wuxia films by the government would lax a tremendous deal after the Chinese Revolution of the late 1940s, which saw the creation of what we've come to know since as the People's Republic, as well as the 2nd assimilation of Hong Kong into Great Britain (Hong Kong being where a GREAT deal of Chinese films, martial arts/Wuxia and otherwise, are generally made). All just in time for the talkie (and soon later, colorized) era of film coming into being, along with far better standards for film preservation in general.

The 1950s would be another banner decade for 20th century Wuxia within an entirely different medium. The 50s saw a MASSIVE resurgence in popularity of Wuxia novels and literature, primarily launched by the absolutely monumental success of seminal and legendary Wuxia author Dr. Louis Cha (better known by his pen name, Jin Yong).

(Dr. Louis Cha, aka Jin Yong, indisputably the single most influential and prolific Wuxia writer of the last 60 years.)

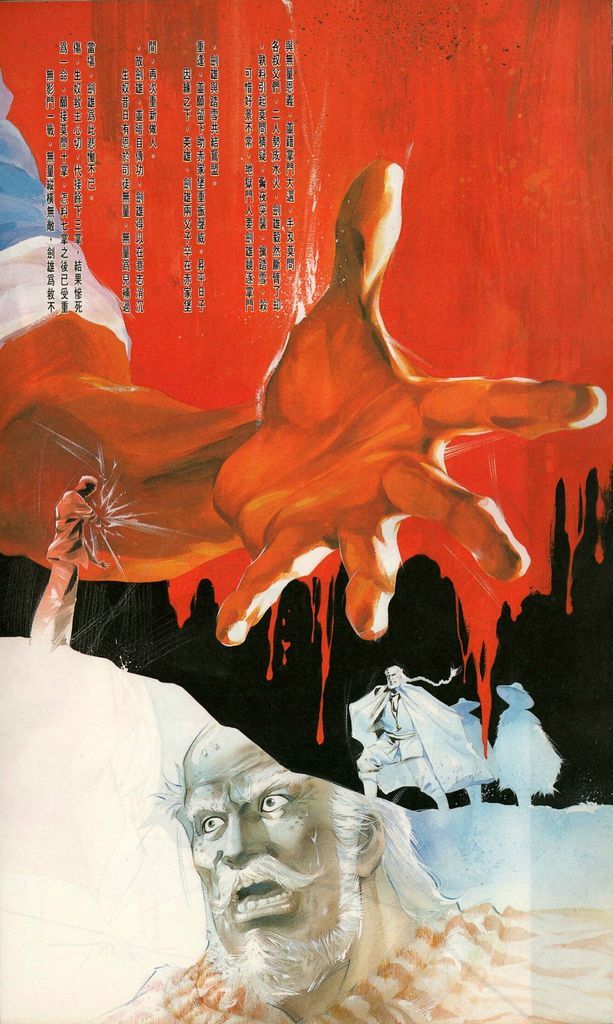

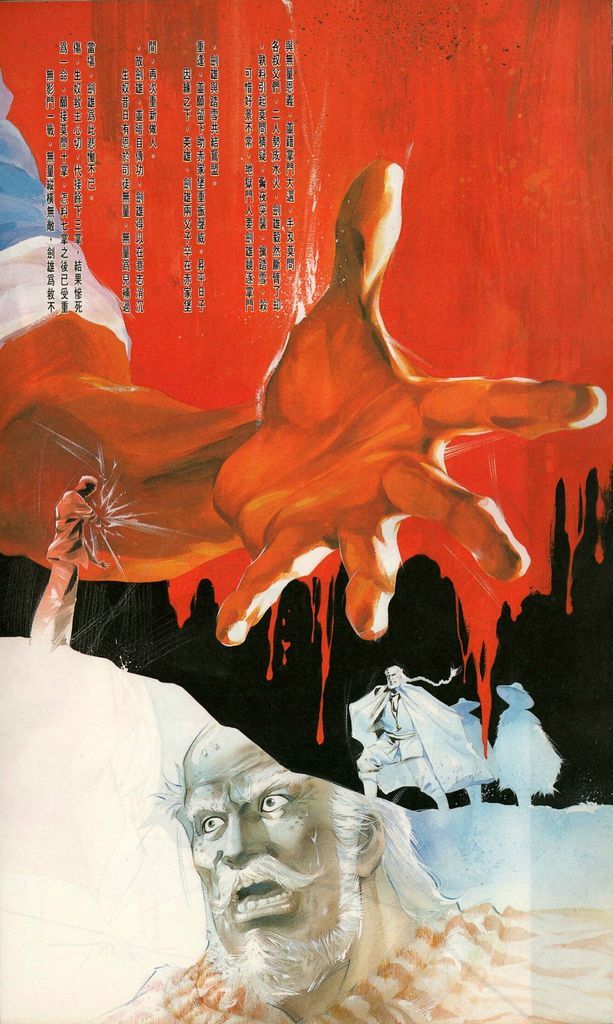

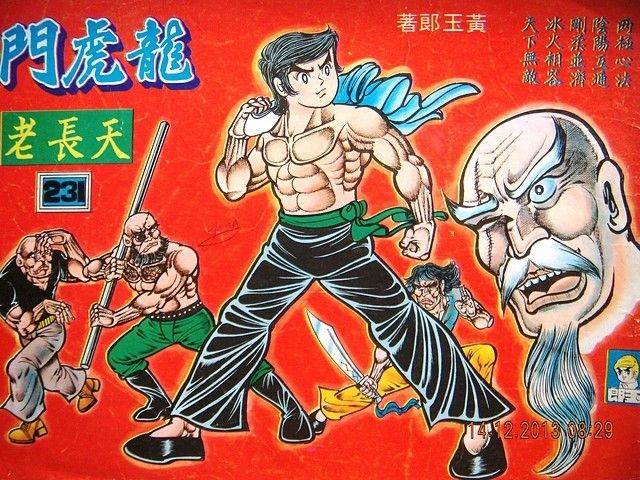

Throughout the better part of the 1950s Dr. Cha would pen an absolutely staggering number of some of the most indispensably important Wuxia tales that would come to define the genre in its modern day context, including the Condor Heroes trilogy (Legend of the Condor Heroes, Return of the Condor Heroes, and the earlier mentioned Heaven Sword and Dragon Sabre), the Smiling Proud Wanderer series, Demi-Gods and Semi-Devils, and far, far too many more to list.

Many of Dr. Cha's novels are still to this day routinely adapted in an unbelievable array of adaptations spanning film, television, radio, animation, comic books/manhua, video games, and the stage, putting his stories easily in the same league of ubiquity as some of the most ancient and time honored Wuxia myths from the genre's ancient origins. Without his contributions, its entirely fair to say that the Wuxia genre's modern day landscape would've been a VASTLY different entity entirely.

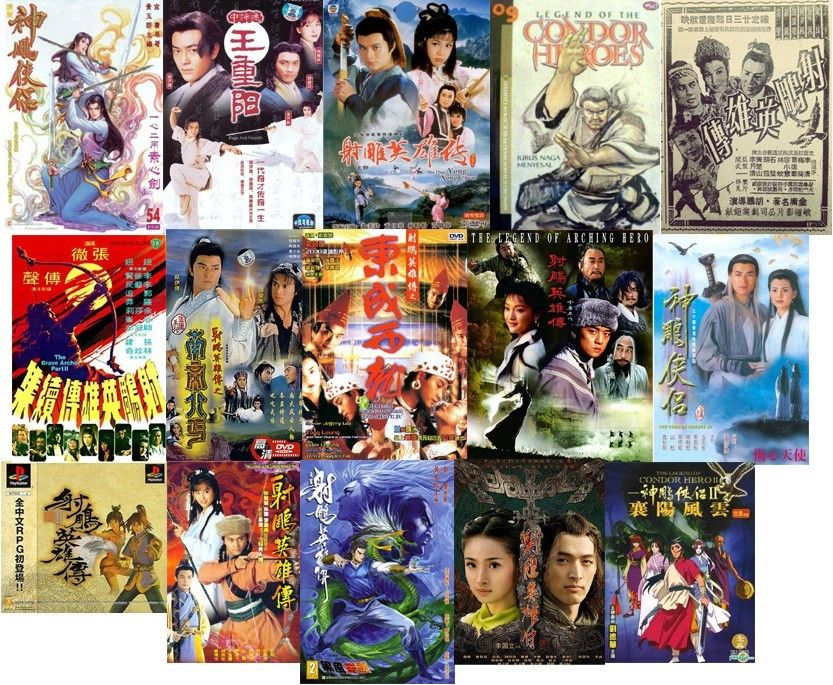

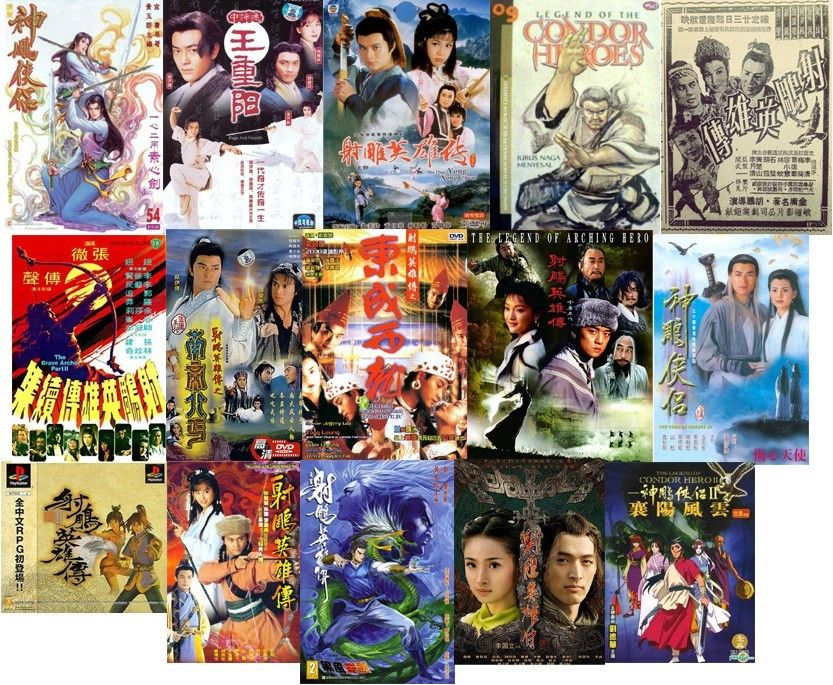

(The Wuxia stories of Louis Cha have invaded every square inch of media for the last 60 years. Pictured above are a sampling of different individual adaptations just for solely Legend of the Condor Heroes alone.)

Other notable Wuxia novelists would also come about during the 50s, including Gu Long, Liang Yusheng, and Sima Ling, making the decade generally seen as the defining golden era for modern literary Wuxia.

Back on the film end of things, more Wuxia talkie serials would be made throughout the 1950s and early 1960s (the first ever film adaptation of the Buddha's Palm mythos being a significant one), until the advent of a significantly HUGE player in the Chinese filmmaking world (particularly that of martial arts and Wuxia films): Shaw Brothers Studios.

Cue the fanfare...

Founded by brothers Runje, Runme, Runde, and Run Run Shaw, the impact of Shaw Bros. Studios on the martial arts filmmaking landscape is utterly impossible to succinctly summarize. A juggernaut that utterly and indisputably DOMINATED the martial arts filmmaking landscape throughout Asia all throughout the 1960s and 1970s, Shaw Studios was a well oiled machine that cranked out literally dozens upon dozens of films a year at their apex. The vast overwhelmingly majority were martial arts films, but they would also dip into other genres as well, including horror, romance, drama, and even at one point Tokusatsu (seriously).

Their only truly significant competition, which first came about in the early 70s, was Golden Harvest Studios, who would be for some years the only major Chinese film studio - also specializing heavily in martial arts films - to successfully hold their own against Shaw Studio's dominance. Indeed during the 1970s (a famously banner decade in general for Chinese martial arts cinema), they were effectively “The Big Two” of kung fu filmmaking, effecting an almost Marvel vs DC Comics/Nintendo vs Sega-like rivalry.

Does this remind you of anything?

A major difference between the two studios however (particularly more so in their earlier years) was their treatment of and attitudes towards Wuxia. While Shaw Brothers produced a TREMENDOUS number of incredibly outlandish and over the top wuxia films alongside their more grounded, straightforward martial arts films, Golden Harvest early on identified themselves as the more “grounded, gritty, realistic” alternative, and who - while still producing a certain amount of them - overall substantially downplayed Wuxia within their overall output in favor of much more (comparatively speaking at times) realism-rooted kung fu films.

Legend has it that this was a significant factor in Golden Harvest scoring one of their most crippling long-term victories over Shaw Studios in the 70s: their signing of a certain martial arts performer by the name of Bruce Lee, who was quite famously not a very big fan of Wuxia (indeed at times a rather outspoken detractor of it) and greatly preferred more grounded in reality martial arts filmmaking. Images have floated around for years of Lee, during the period where Shaw Studios were still attempting to court him away from Golden Harvest, being costume fitted for various potential Wuxia roles, which Shaw generally made mandatory to all their actors: something which likely did not please or excite him too much.

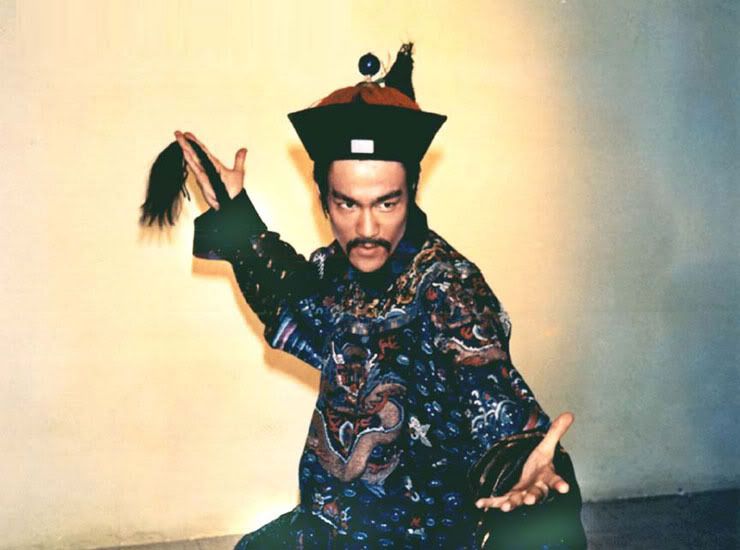

(What could have been: Lee as a stuck up, pompous Mandarin scholar who learns mystical kung fu and becomes an embittered, badass villain/anti-hero of the Wulin world? Admit it, you want a peak into the alternate reality where that movie actually happened.)

Of the many, countless reasons for why Bruce Lee was a Big Goddamned Deal in the world of martial arts cinema (which you can easily read and view untold decades worth of writings and documentaries on the subject) was an especially HUGE leap forward in the evolving of martial arts filmmaking and on-screen fighting that he, and Golden Harvest in general, where largely responsible for.

A stickler for naturalism and a staunch forward-thinking progressive (hence a big part of his dislike of Wuxia: Lee found the genre hokey and rooted too deeply in the past, traditionalism, and increasingly out of date martial arts filmmaking principals, and thus saw them as a negative, discrediting factor in the rest of the world outside of Asia taking Kung Fu cinema seriously), Lee was among many other things a trailblazer and pioneer of breaking on-camera martial arts choreography away from the stiff, dance-like choreography of Peking Opera plays, and instead bringing a previously unheard of level of naturalism and realism to how the fights felt and came across.

This would, gradually and over time, revolutionize how ALL martial arts fighting would be depicted on camera. While many Golden Harvest performers, choreographers, and stunt people would quickly adapt to and embrace this incredible new form of fight choreography, Shaw would for a great many years remain stubbornly resistant to it. Beyond giving Golden Harvest a distinct identity apart from the then-towering juggernaut of martial arts cinema that was Shaw Studios (and thus allowing them to compete directly against them in ways that other studios struggled to), this would of course inevitably over time bite Shaw Bros. in the ass in other equally BIG ways... but we'll get to that shortly.

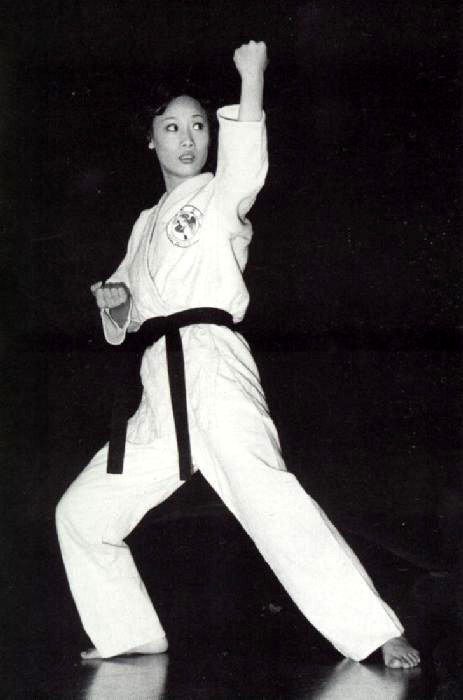

(Old school vs new school. On the left: stilted, stage-like left, right, left, right! One, two, three, four, one, two, three four! On the right: silk-smooth movement, a sense of unpredictable spontaneity, and gritty viciousness. As early as the dawn of the 70s, Lee was truly ahead of the curve.)

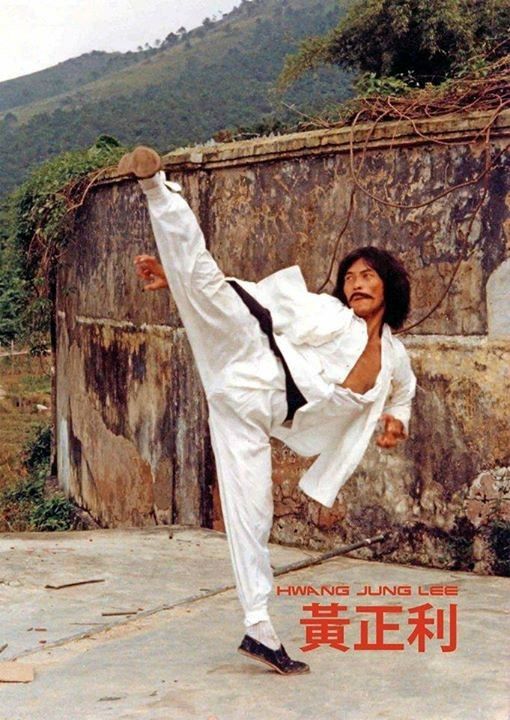

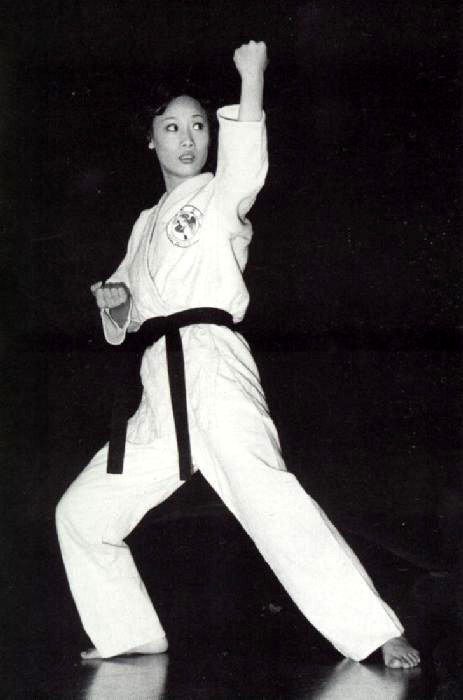

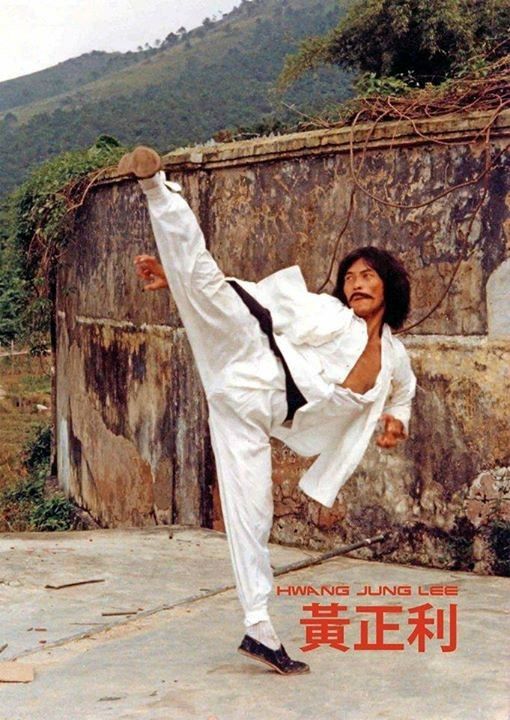

With Lee as the front and center-most superstar in Harvest's corner, other talents would emerge from the upstart studio to rival Shaw's stable of performers, including Carter Wong, Hwang In-Shik, Angela Mao (probably one of the all time most beloved and iconic female martial arts superstars who ever lived and one of my childhood heroes), and of course the incredibly charismatic and impossibly skilled Hwang Jang Lee (another martial artist who I positively worshiped for my entire adolescence).

All would star in numerous martial arts films that were often hard-edged, gritty, more grounded counterpoints to Shaw's overall larger fixation on ancient Chinese Wuxia lore and over the top stylized mystical martial arts fighting and tropes, with Golden Harvest as a studio only comparatively rarely venturing into Wuxia themselves (and certainly never with Bruce Lee's participation natch).

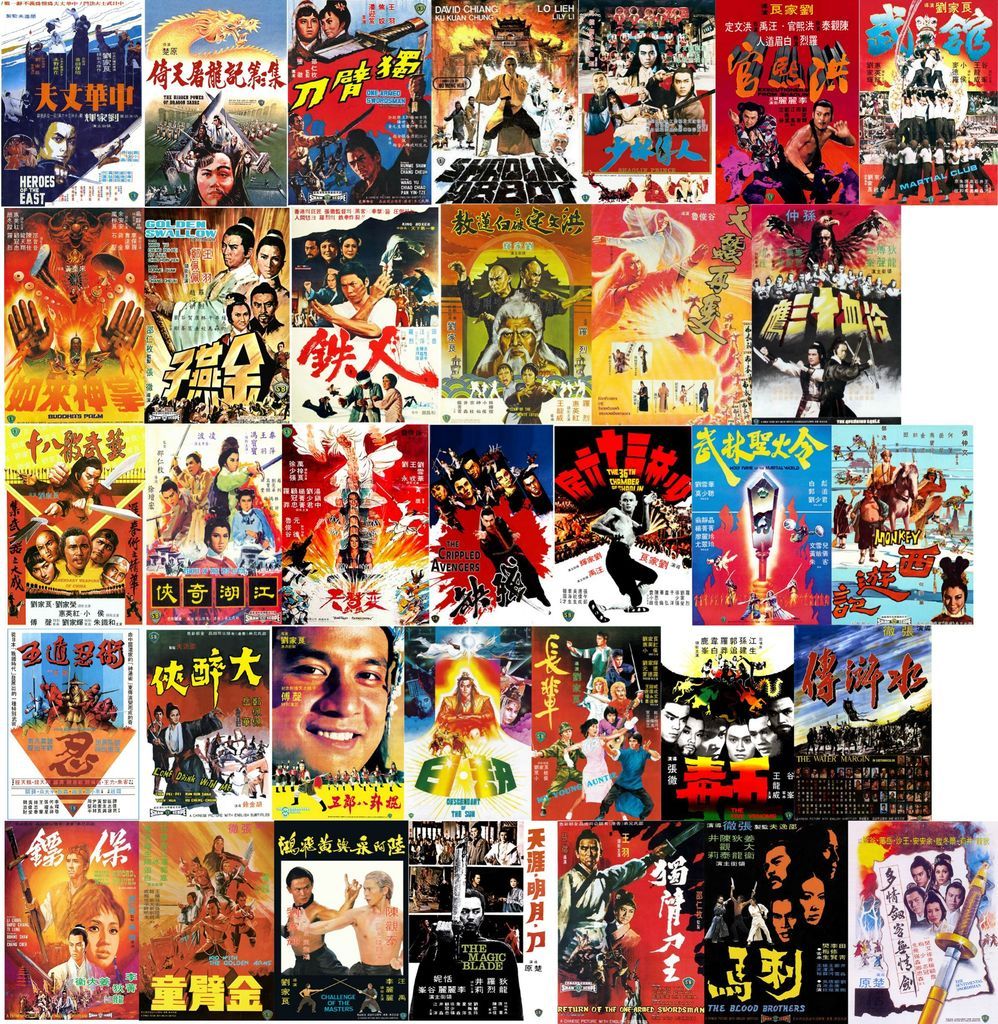

Nonetheless, even with the more relatively down-to-earth Golden Harvest as a constant ever-present thorn in their side, Shaw Brothers were for a few decades THE face and voice of Wuxia in Asian filmmaking. The sheer staggering number of films they produced in Wuxia alone (much less all their other genre endeavors) defies comprehension, many of which remain influential, stone cold classics to this very day.

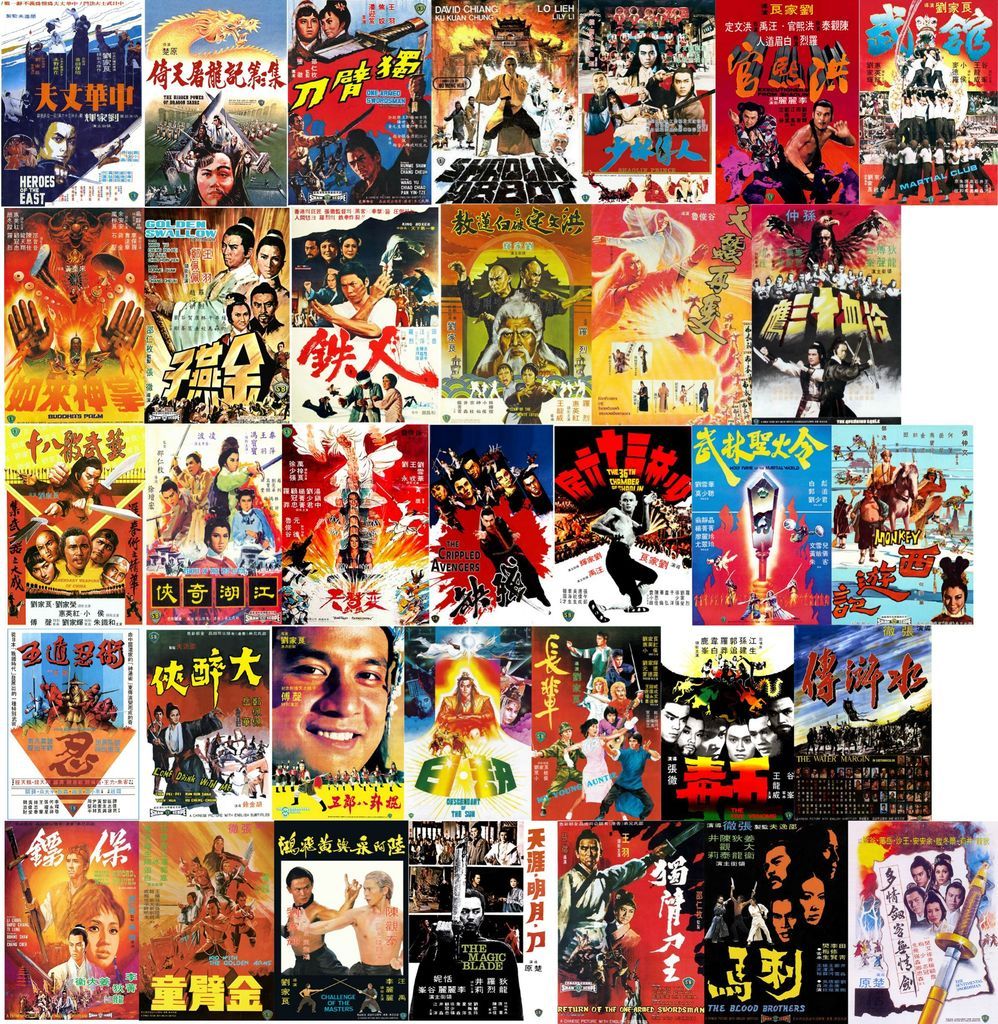

Timeless classics Golden Swallow and Come Drink With Me, adaptations of Water Margin and Journey to the West, The Magic Blade, King Boxer, One-Armed Swordsman, Fist of the White Lotus, Five Deadly Venoms (introducing to the world the Venom Mob, a troupe of incredibly charismatic, versatile, and well-liked martial arts actors), the nearly-lost gem The Black Tavern, Have Sword Will Travel, Temple of the Red Lotus (Shaw's own remake of the above-noted lost silent classic The Burning of the Red Lotus Temple), and of course their defining crown jewel 36th Chamber of Shaolin... Shaw's output is among the most rightly celebrated and beloved in wuxia (and just general martial arts, which I barely even touched on above) film fandom, more than justifiably so.

(One of the most towering legacies in all of martial arts film history.)

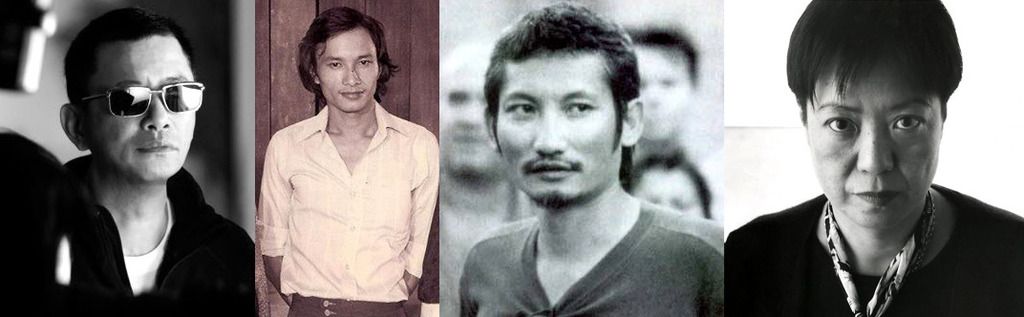

Countless superstar names in kung fu filmmaking would come out of Shaw studios, from directors Chang Cheh and Lau Kar-Leung - both responsible for a vast majority of Shaw's best films, with Cheh in particular also becoming notable for often blending the fanciful silliness of Wuxia with harsh, graphic violence and gore...

...as well as instantly iconic on-camera talents like Lo Lieh, Jimmy Wang Yu, Kara Hui, Wang Lung-Wei, Cheng Pei-Pei, Ti Lung, the tragically gone-too-soon Alexander Fu Sheng, the aforementioned Venom Mob (including one of my personal all time favorites, the disgustingly talented Philip Kwok), and of course the one and only great himself, Gordon Liu (the overwhelmingly most likely candidate for the principal basis of Kuririn).

While there were certainly some stray, but no less immensely notable martial arts and Wuxia films made outside of either Shaw Bros or Golden Harvest - particularly by the great King Hu, who made wuxia movies for BOTH studios, as well as outside of them entirely: A Touch of Zen and the original Dragon Gate Inn (two of the all time greatest Wuxia films in history) were notably made by Hu without either Shaw or Harvest, as well as some very notable Taiwanese-produced indie kung fu films – overall the 60s and vast bulk of the 70s were indeed the golden era of Shaw.

Many more modern martial arts/wuxia filmmaking staples would evolve and grow to prominence thanks largely to Shaw, from atmospheric, Spaghetti Western-like foreboding pacing and tension building (your pre-fight “drawn out staredowns” and the like), as well as their instantly iconic and distinctive style of musical scores (traditional Chinese orchestral, very brassy and with just a hint of 70s funk): and for Westerners of course, the horrendously, gloriously bad dubbing.

Wuxia in Modern Media Section II: The Grindhouse Years – First Crossover Success in the Western World (1970 - 1979)

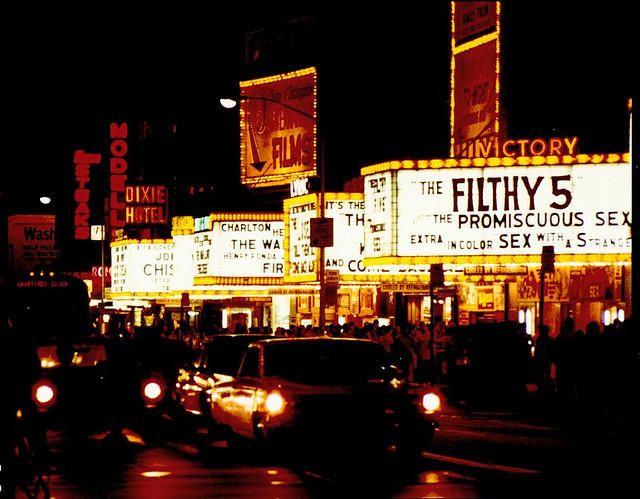

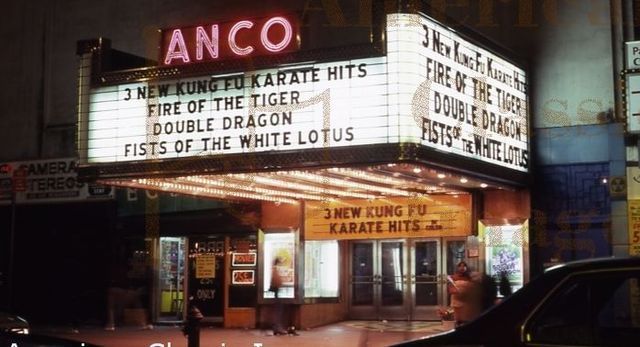

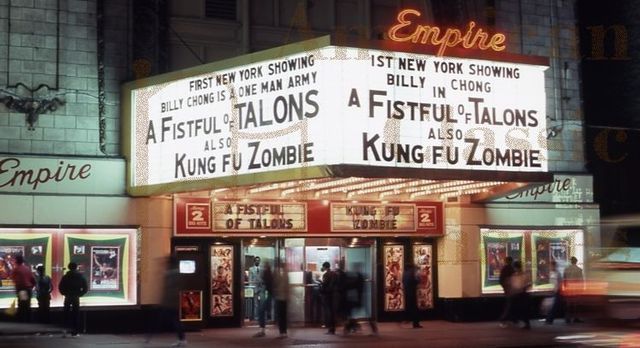

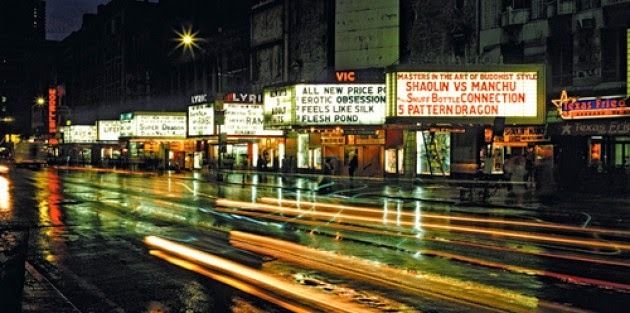

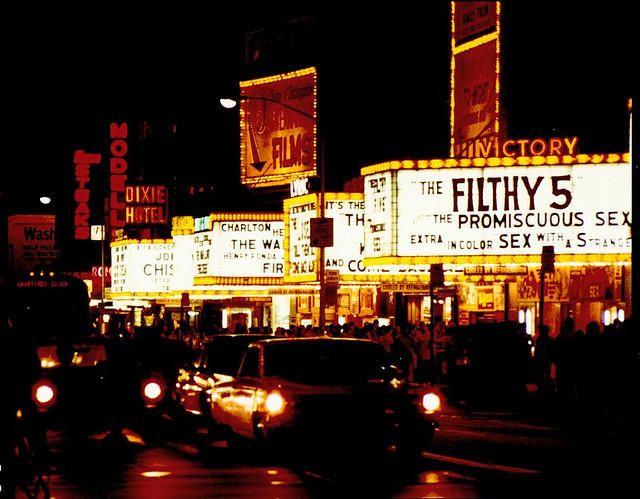

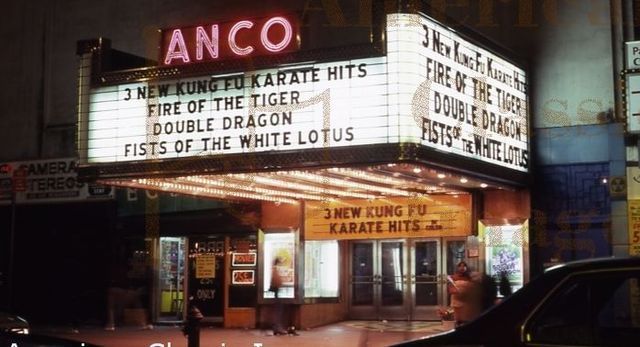

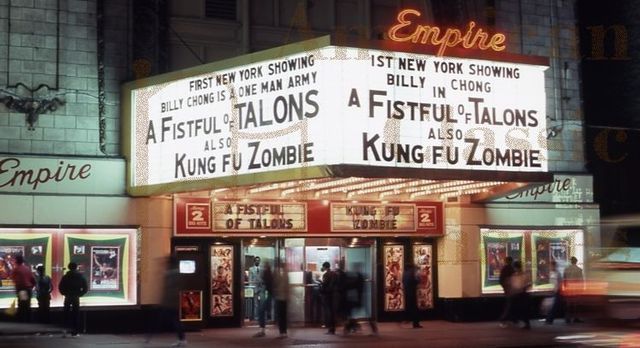

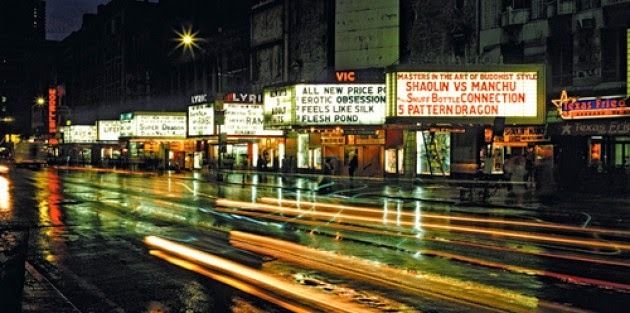

Speaking of Shaw's (and Harvest's) impact on us Westerners, I'd be remiss if I didn't point out that end of the equation. Over in America during the late 1960s and throughout 1970s (and 80s even) there was a growing new venue for film viewing known colloquially as the Grindhouse Theater.

Some of you may have heard the term in more recent-ish years thanks to constant stumping/promoting of it by the likes of Quentin Tarantino, but for those of you who are still completely oblivious to such things, I'll explain (as this is CRUCIALLY important to the topic anyway).

Grindhouse Theaters were low rent, often incredibly filthy, scummy, decrepit shithole little movie theaters that largely operated in major urban cities (particularly in New York). Generally found in the poorest, most dangerous and crime-ridden areas, Grindhouse Theaters were as FAR from mainstream viewing as you could conceivably get.

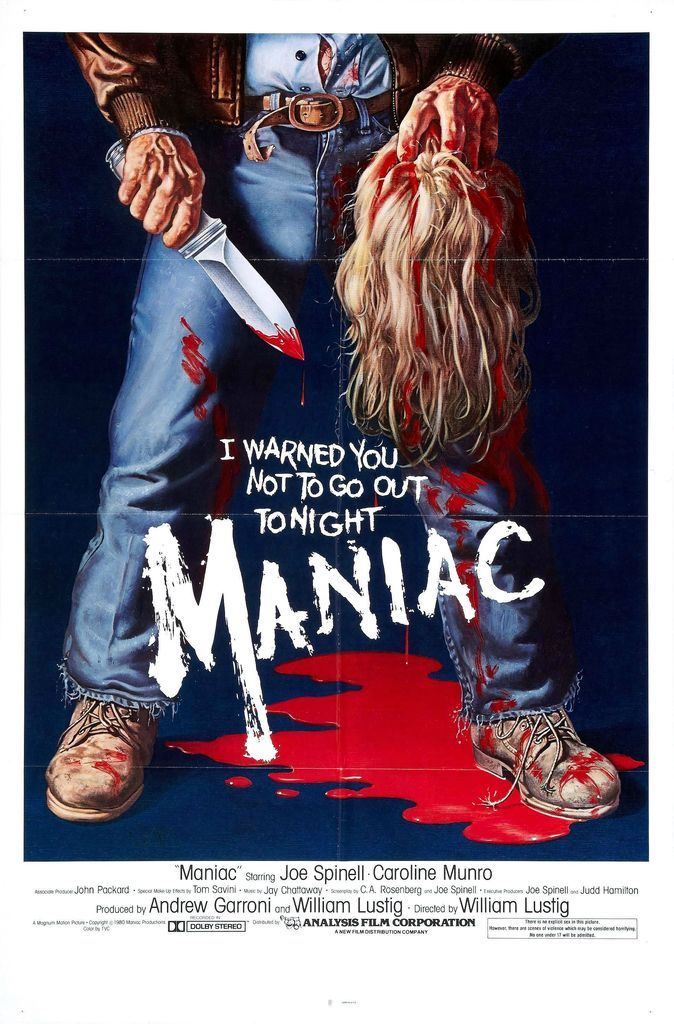

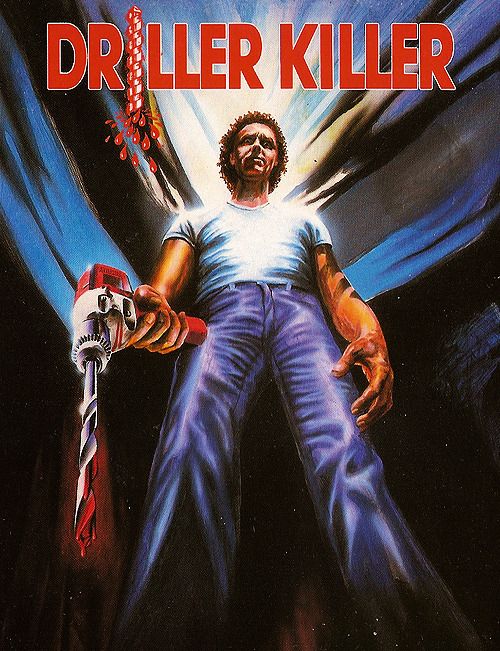

Specializing in showing amorally exploitative films (from rape films, to nun fetish movies, chainsaw slasher killer films, biker thug epics, and straight up porn of the vilest, sickest kind) to an audience of (certainly not always, but very often) junkies, trench coat-wearing perverts, and random street weirdos, Grindhouse Theaters were the kinds of places where the skeevy, mangy, leering creep you hope to never run into while walking home alone through the scary part of town late at night might head off to to kill time and relax.

So... what in the atomic powered fucking hell could something like THAT of all things have to do with Wuxia? Plenty.

You see, apart from the sick, twisted shit they were most known and infamous for, Grindhouse Theaters specialized in showing a pretty diverse array of other things as well. As their general choice of locations would denote, Grindhouse theaters were businesses of EXTREMELY limited budget and means. They wouldn't show your average, mainstream, A-list features not only because the sort of clientele they catered to would likely not hold the slightest interest, but also because they straight up often couldn't AFFORD the damn film prints even if they actually wanted to show them.

The film selection of a typical grindhouse theater was as much borne out of economic necessity as it was the incredibly fucked taste of the audiences: these were cheap, dingy theaters located in poor, dingy neighborhoods, and they got exactly the kinds of cheap shit that they could afford to get: and these films were largely so cheap to get in the first place because no self-respecting mainstream theater in the “straight-laced, proper” parts of town had the slightest interest in showing them. Some were crazed indies made by utterly bonkers eccentrics, but others were also Mafia funded: but that's an entirely other story unto itself.

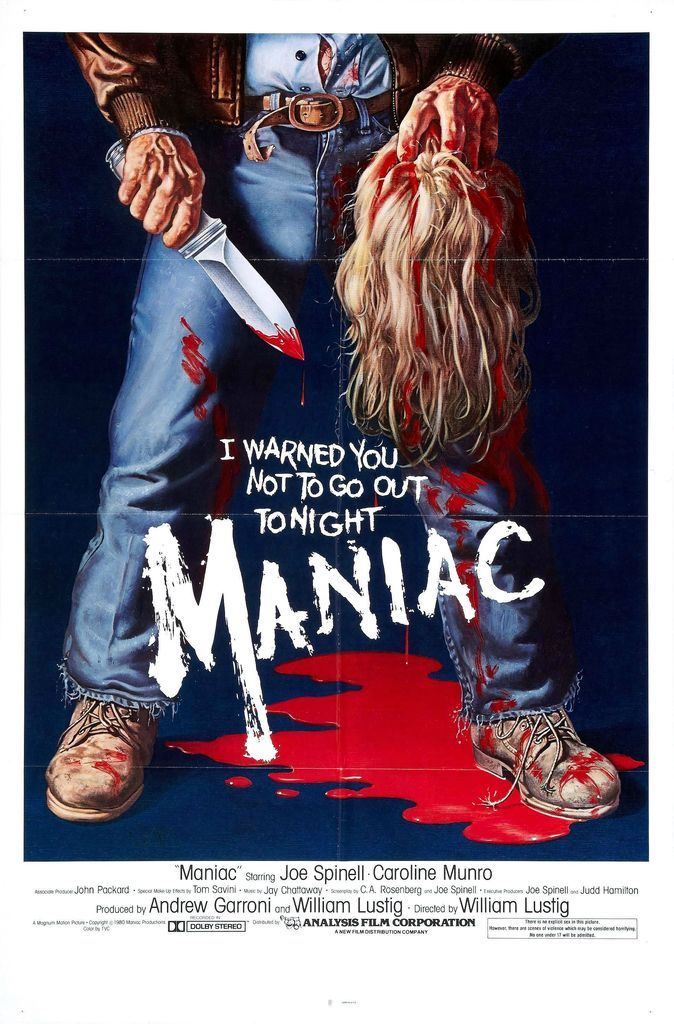

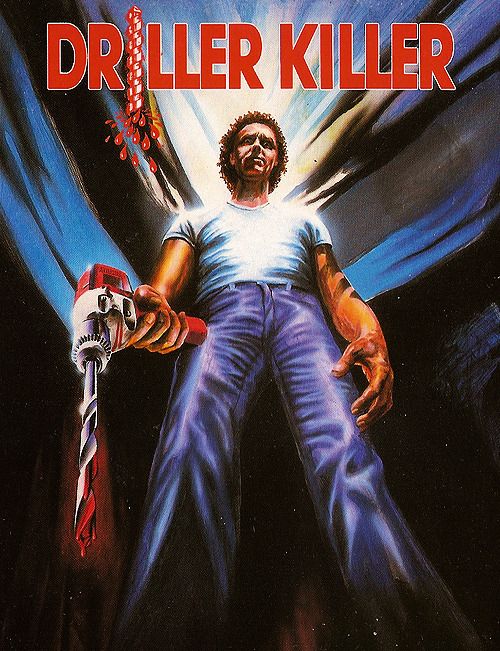

Grindhouse theaters were thus a foster home to the unwanted bastard, deformed, abandoned freaks of the cinematic world. So of course this would include things like scat porn and movies about genital mutilating cannibals and sexually maladjusted serial killers who fuck homeless people to death with power drills.

(Oh yes, that's an ACTUAL grindhouse movie too.)

BUT... grindhouse theaters were also a viable venue for OTHER extremely diverse, fascinating curios besides those.

I doubt I'll be shocking anyone when I note that mainstream America in the 1970s was still a pretty great deal culturally xenophobic. It took a foreign filmmaker of IMMENSE artistic prestige (a Jean-Luc Godard type) to get their stuff seen and appreciated by an American public that was even halfway close to mainstream back then (like say, a college campus-type crowd). Any regular old pulpy genre effort coming from overseas usually had about a snowballs chance in hell of ever getting shown in a regular American theater in mom & pop middle American suburbia, no matter how well made or legitimately interesting it might otherwise be.

Thus grindhouse theaters would often step in and purchase prints for all sorts of hugely interesting (and absolutely bonkers bizarre) foreign movies to further pad out their nightly showings of gore, tits, and sleaze. Spaghetti Westerns and arty giallo thrillers from Italy (that walked a VERY fine tightrope balance smack in between legitimately elegant and classy as well as luridly filthy and skeevy) were among the favorites, but also among them was... Chinese kung fu films. Both standard kung fu and supernatural Wuxia.

(Come for the gang-rape and gore-porn, stay for the silly-fun antics of ancient Chinese Kung Fu mystics flying about.)

So it was that, as much of a shock as this may come to some folks here, the martial arts/Wuxia genre gained its very first ever true burst of popularity and exposure in North America in the 1970s primarily from the same cesspit theaters that also heavily trafficked in the grossest, most vile and taboo cinematic sewage that crawled from the 70s exploitation circuit. Your average round eyes of the 70s probably got their first ever glimpse of Ti Lung or Lo Lieh flying around on wires and firing mystical laser beams from their fingertips at Chinese demons from the same double bill showing where they could also see an actual real life medical cadaver getting eyeball-mutilated in loving closeup in They Call Her One Eye.

Wuxia and Grindhouse cinema in fact actually have a very tight history/relationship with one another in the U.S. that spans at least a couple of decades (70s and 80s).

Shaw Brothers' King Boxer (shown in the Grindhouse Circuit under the alternate title “Five Fingers of Death”, which I've always personally preferred) was THE first ever smash hit Chinese Kung Fu film in America, largely preceding even Bruce Lee's crossover into more mainstream Western popularity. The success of King Boxer/Five Fingers of Death lead to a HUGE pouring over of CONTLESS kung fu and wuxia films in grindhouse venues across the country for a great number of years following; a great many of them Shaw Bros. and Golden harvest productions, complete with the legendarily terrible English dubbing that they'd largely become famous for for many, many decades down the line up to this day.

Aaaaaand cue that OTHER fanfare...

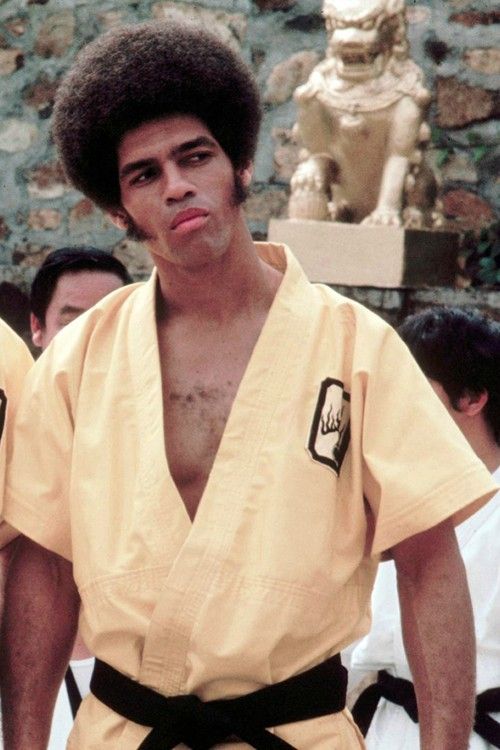

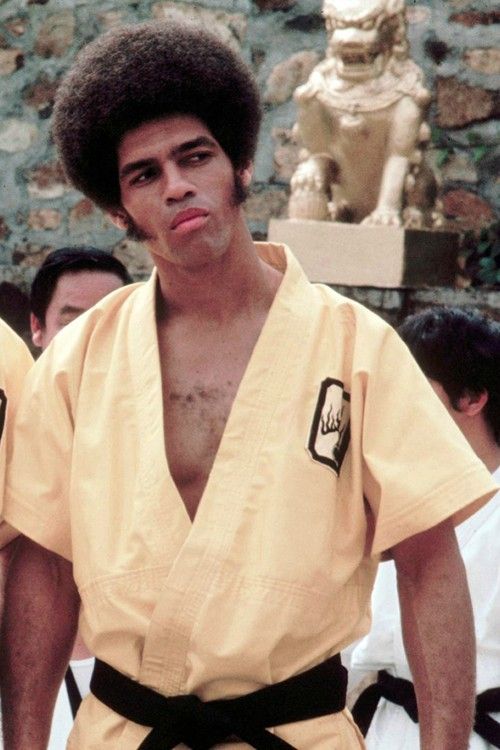

This as it turns out is also the origin of the immense popularity of martial arts films among black/African American culture. Black patrons were very commonplace in grindhouse theaters as they were located in a great many largely black ghettos in the 70s (hence Blacksploitation films, also a grindhouse staple). Of all the kinds of films shown in grindhouse theaters, Kung Fu and Wuxia films (apart from blacksploitation films at least) were BY FAR AND AWAY the biggest runaway success amongst black audiences.

Its not very hard at all to see why: remember the anti-authoritarian streak I talked about that ran in a lot of Wuxia? A tremendously great deal of Wuxia and Kung Fu films centered on strong, able bodied martial artists from often poor, rural communities that are under the boot-heel of a powerful, oppressive government/dictatorship. Often the hero would rise up against the oppressive warlords in the name of their village and, with little more than raw fiery righteous anger and talented skill, would knock said-oppressive tyrannical warlord/authority figure down a few pegs with a sound ass-whipping.

(On the left: martial artist/actor Jim Kelly personified the massive overlap between Kung Fu cinema and black grindhouses in the 1970s. On the right: rapper and founding Wu Tang Clan member RZA has taken up that mantle throughout the 1990s and 2000s, acting as one of the biggest celebrity fans/proponents for martial arts fiction and Wuxia to the point of offering vastly knowledgeable and insightful commentary tracks on DVDs/Blu Rays for a number of older classic Wuxia films and recently directing a Wxia film of his own, The Man With the Iron Fists.)

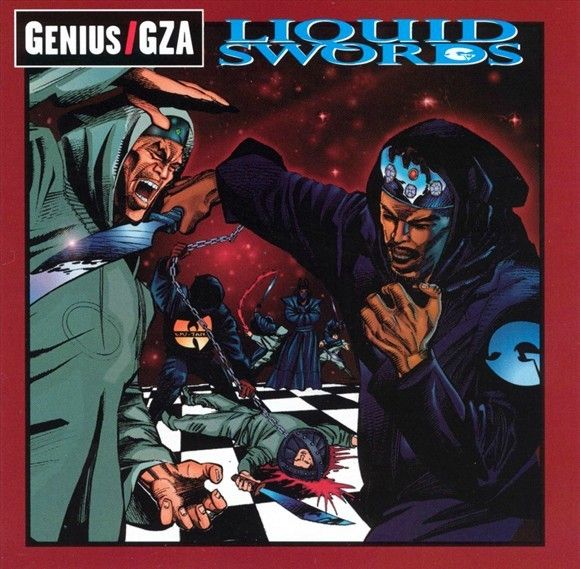

If you know a DAMN thing about black history in the United States, particularly pertaining to life in the slums/hoods, the appeal of these kinds of films to poor black audiences should be STRIKINGLY apparent. This would of course transfer over into hip hop culture as well once that came into being in the 80s. This is the very wellspring from which you get hip hop groups like the Wu Tang Clan and so forth (which now you also know from earlier where even THAT name originates from). In many respects, this closely mirrors the original appeal that the earliest silent Wuxia films had with lower class, poorer Chinese audiences in the 1920s (and which the then-still rising Communist government saw as a threat).

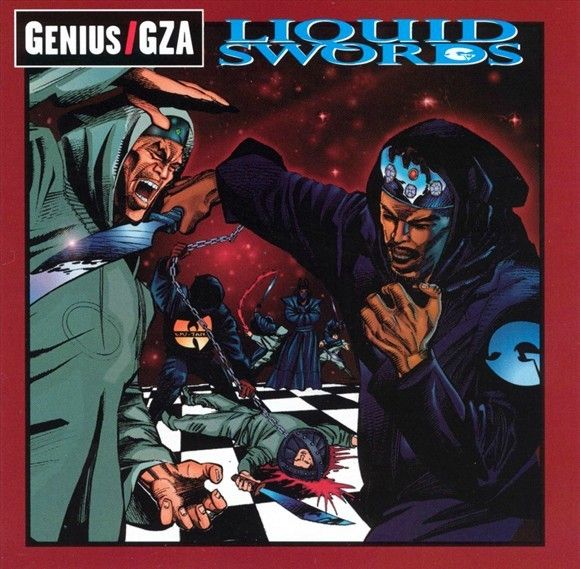

(Fun fact: “Legend of the Liquid Sword” is as it turns out the title of a Wuxia movie, which is where the iconic GZA album in turn takes its title from. Its a pretty cool flick too.)

This would thus mark the earliest beginnings of Wuxia and martial arts fiction in general creeping its way Westward out of Asia and into American pop culture. And not long after Bruce Lee would find massive crossover fame in mainstream America, thus bringing the popularity of martial arts cinema further out of the black ghettos and into the straightlaced middle class white world.

However as noted, Lee wasn't particularly fond of Wuxia, and kept his (tragically short) output completely relegated to grounded, non-mythical-bsed kung fu. As Lee was for the time THE mainstream face of Asian martial arts cinema to regular Americans (and indeed the primary driving force behind its sudden explosion in wider popularity), standard, non-mystical kung fu was what most of the non-grindhouse-patronizing Western mainstream was left familiar with.

Lee was also signed with Golden Harvest, who as I noted were FAR less reliant upon Wuxia than Shaw was at that point, and indeed were at the time much better known for their more reality-based (and often quite 70s gritty), decidedly non-fanciful kung fu films: thus the overall Golden Harvest style was far better known in the 70s to mainstream American viewers than Shaw's more outlandish magic and myth-based kung fu films.

Nonetheless the metaphysical zaniness of Wuxia had still indeed made its mark here in the U.S., but it was largely relegated to the underground, the niche, hardcore nerds, and the sleaze pit theaters in the sleaze pit parts of the big cities.

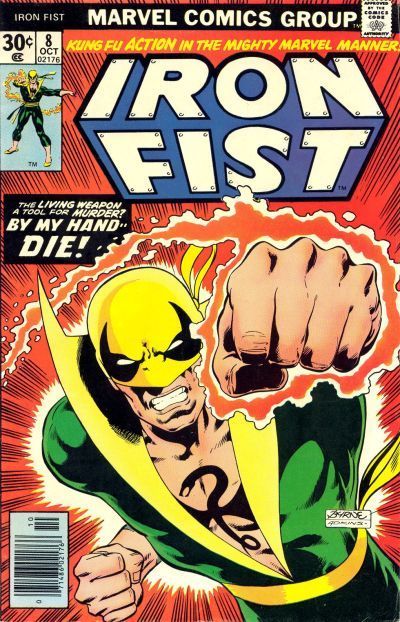

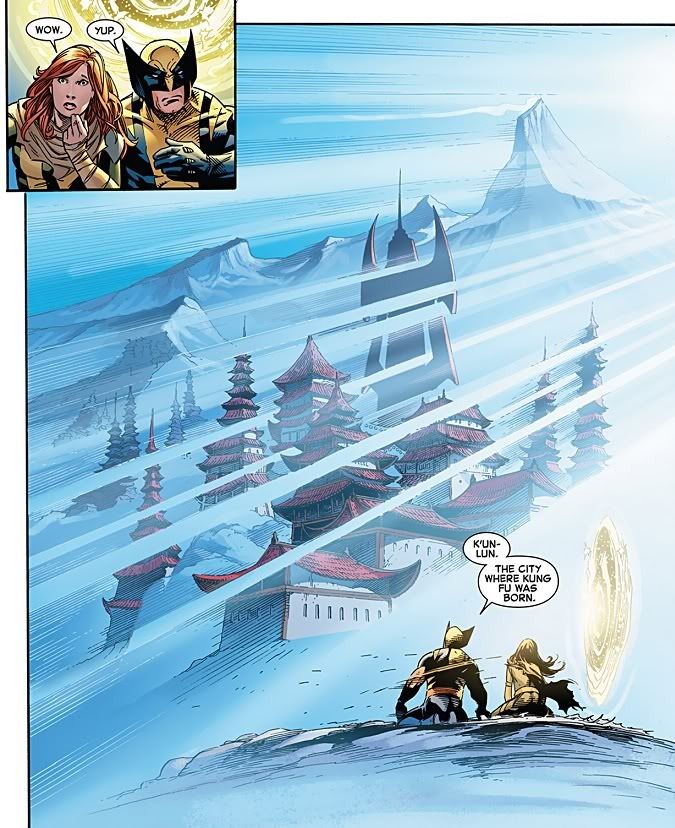

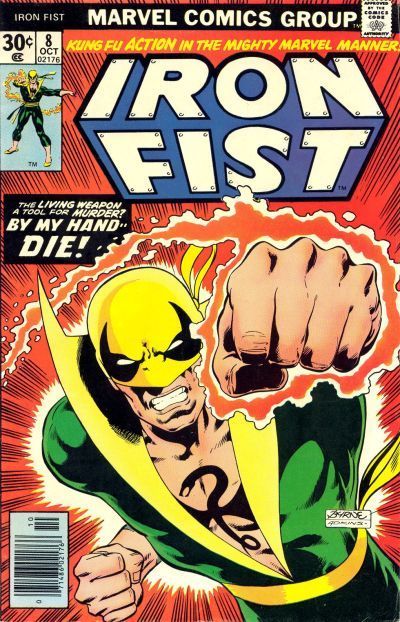

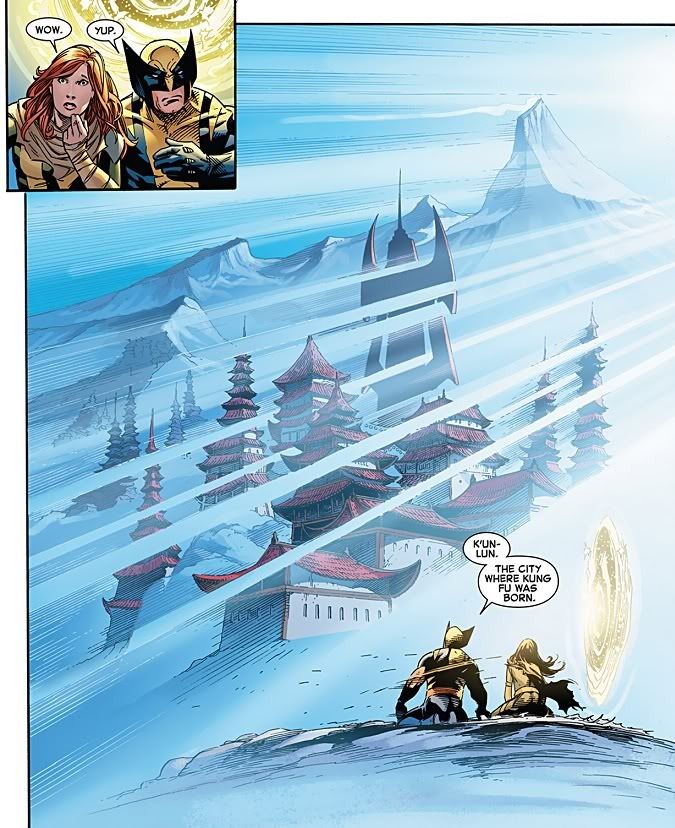

Still, it would crop up from time to time in various Western outlets such as Marvel Comics when in the mid-70s they created Shang Chi, Iron Fist (their own resident Wuxia-themed superhero), and the mystical hidden lands and city of K'un-Lun (Marvel's own rough approximation of Jianghu, a magic hidden area of China where all manner of Wuxia lore is real).

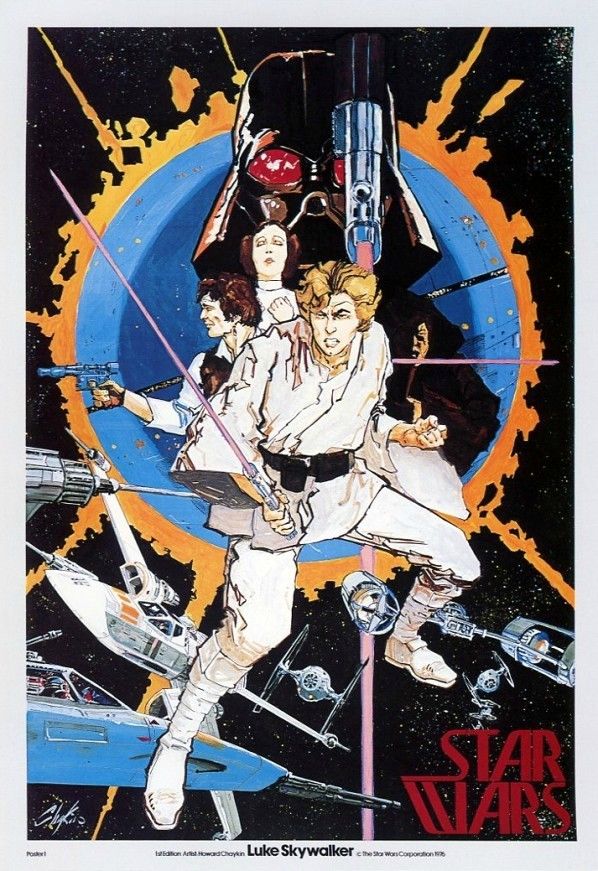

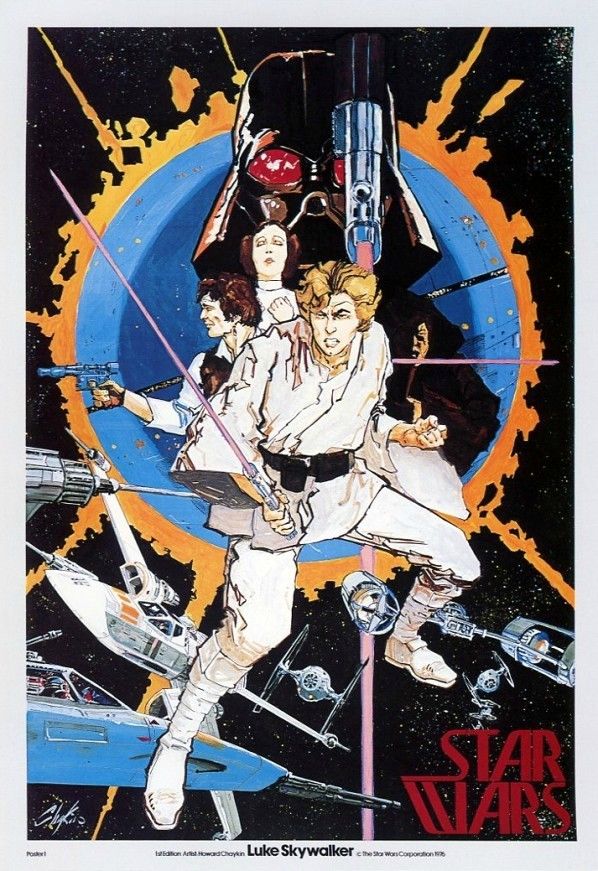

The single most famous example of elements of Wuxia lore popping up in a piece of mainstream Western media during this time period, without question, is of course the original Star Wars trilogy. That Star Wars is a total hodgepodge of disparate pulp influences, both domestic and foreign, has long been common knowledge. But amongst its morass of pulp film serial, WWII drama, space opera, heroic myth, and Chanbara/Jidaigeki (classic Samurai) influences is also Wuxia.

(A Flash Gordon Serial re-imagined with flourishes of Wuxia, Chanbara, Joseph Campbell, and WWII propaganda: Star Wars in its own way was a bit of foreshadowing of what was to come for Wuxia in its native land.)

Wuxia is in fact arguably among Star Wars' most integral influences, certainly at least when pertaining to the lore of the Jedi Knights: the Jedi themselves are just as purposefully reminiscent of Xia/the Wulin community as they are classic Samurai archetypes, and the concept of Chi/Ki as a universal life energy inherent within nature is at the heart of The Force, which is generally agreed to be one of the most fascinating and alluring elements of the original trilogy by most fans.

Not only does the Force closely mirror Ki at a basic conceptual level, but even in terms of how its portrayed on screen, via different sects and clans of characters being able to tap into it with hard training thus allowing them to use the power of The Force/Chi to “sense” one another through it as well as using it to mentally levitate objects and increase their own physical prowess to leap about with superhuman agility. Even Luke's famous training sequence on Dagobah with Yoda is directly reminiscent of the sorts of metaphysical kung fu training that most Xia undergo in a great many Wuxia stories.

Before we proceed any further into this, at this point I'd like to take a moment to apologize for how generalized I've kept large swathes of this whole info dump session thus far. But you have to understand something: at the risk of repeating myself and belaboring a point here, it can never be overstated the palpably overwhelming degree to which Wuxia is a MASSIVE fucking genre with an INCREDIBLY dense and rich history and array of individual stories and various retellings and reinterpretations of many of those stories spanning back countless centuries across SUCH an insane array of storytelling mediums.

Towards the end stretch of my tenure as a regular here, as I'd come to realize how staggeringly ignorant of this entire genre's existence much of this community (and wider modern Western Dragon Ball fandom in general) was and started talking about it a bit more in some of my later posts (almost coming within a hair's breadth at one point of appearing on the podcast to talk about aspects of it) I'd gotten the distinct, overwhelming impression from various other regulars here that I was beginning to be seen around these parts as some sort of resident “Kung Fu media expert” and academic scholar of all things relating to Martial Arts genre fiction and Wuxia in general.

And here's the thing about that: I couldn't be anything the least bit further from that, nor have I ever once remotely claimed to be in the first place. Despite how creatively I can string together a sentence or two and despite how long I can drone on and on about a constant, never-ending torrent of trivial bullshit, don't for one second think that I'm anything other than a total fucking dumbass when push comes to shove.

I've known throughout my life a fairly wide, diverse assortment of ACTUAL smart people, who in numerous fields of subject matter, up to and including this one here (Wuxia and ancient Chinese mythological Kung Fu lore) can soundly hand me my fucking ass without even pretending to put forth any effort into it. There's any NUMBER of Wuxia enthusiasts out there who can legitimately lay claim to being actual no-bullshit academic-level experts on the matter and could do what I'm doing now (overviewing just the barebones basics of the genre) whole vast, infinite WORLDS better than I've been doing thus far.

Compared to them, I'm a fucking simpleton. I'm the Beavis and/or Butthead to their Daria (probably more of a Beavis if I had to pick). The aptness of that particular analogy with regards to this topic is actually sort of integral to my own history as a Wuxia/Dragon Ball fan and will be revisited and explored in greater detail later on.

I digress. For now though, let me just apologize dearly to you all for being the “best” that you folks currently have to work with on this for the time being. That in itself is incredibly sad as, as I've said, there's FAR infinitely better knowledgeable scholars of all things Wuxia out there than myself; people who actually know Chinese and can quote you ancient Youxia poetry and literature chapter and verse and relay to you all sorts of incredibly fascinating history on some of the earliest ever incarnations of many of these stories and character-types. My knowledge of the truly ancient, nitty gritty historical Wuxia prose and lit predating the 20th century is nothing if not embarrassingly rudimentary and basic.

My biggest so-called “bragging rights” in this area is my having struggled my way through a couple of college translations of The Water Margin, Journey to the West, and about 70% of Romance of the Three Kingdoms in elementary school, doing a 6th grade book report on Li Bai...

(From a dog-eared collection of his poetry that I got in a dumpy-ass pawn shop for what couldn't have been more than 5 or 10 bucks)

...reading some online FAQs about a few select untranslated novels and the genre in general back in the early 90s, and watching a few raw, untranslated peking opera performances of a few ancient Wuxia myths on International Channel and a few Hong Kong cinema websites (during the really early days of when RealPlayer and Quicktime were “cutting edge”) in the mid to late 90s with what I can assure you was almost ZERO understanding whatsoever of any of the deeper nuances of the shows.

Voila, there, that's almost the entire length and breadth of my “academic/classical/historic” Wuxia expertise. Largely everything else I've known about it my whole life has been divined almost exclusively from a steady diet of Chinese comic books (aka Manhua), video games, bootleg VHS tapes of ungodly countless films, and access to International Channel back in the 90s (which played marathons of various live action Wuxia TV shows every single weekday afternoon, almost exclusively raw and unsubbed). Fucking pathetic.

Rest assured I am but an extremely, painfully average fanboy of this stuff, bred largely on the film and comic book output of the genre in the late 80s/early 90s (me being if nothing else a massive creature/product of the late 80s/early90s), as the vast overwhelming majority of my selection of example images and gifs will certainly attest.

And its with that in mind, that we'll be moving away from any laughably piddling attempts on my part of tackling the truly ancient, historical background of the genre and focus firmly on its contemporary media history... with a particular emphasis on film.

Since this whole section is essentially going be a nerd history lesson, this is without question going to be the overwhelmingly largest, densest portion of this entire massive info dump: so its probably best that it be broken up into a few sub-sections for the benefit of clarity and everyone's sanity.

Wuxia in Modern Media Section I: The Classic Years (1929 - 1970)

Considering Wuxia's immense cultural importance and near-universal, unceasingly bottomless popularity in its native China almost all throughout its history, little time was wasted before it made its mark in early 20th century media. Wuxia has been a part of more modern Chinese media and pop culture for almost literally as long as the existence of film itself.

That's right kids, that means that Wuxia was also very much around for the era of Silent Film and Film Serials.

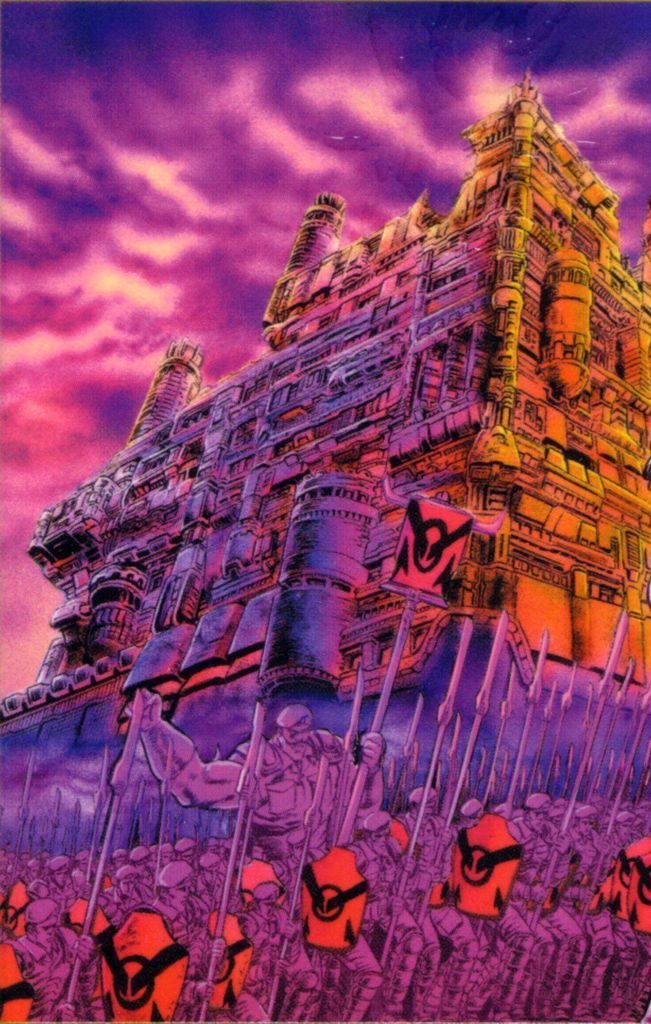

Pictured above is a still from The Burning of the Red Lotus Temple, one of the earliest Wuxia films... possibly THE first ever Wuxia film (making Wuxia a fairly late genre entry in the history of silent film). A serial released in a massive 16 installments from 1928 to 1931 and adapted from a newspaper strip (told you this genre invaded literally EVERY form of storytelling in existence), it tells the story of a long, daring rescue of a martial arts master by his devoted students from a large temple filled with hidden enemies, traps, and other dangers.

The temple in question of course is the infamous Red Lotus Temple, a hideout for cutthroat criminals who's MO is masquerading as benevolent Monks (the Red Lotus Temple would make return appearances in a great many more Wuxia films and stories over the ensuing decades, even up through the 90s).

The influence of this film upon the rest of the genre across the rest of the 20th century and beyond absolutely cannot be overstated. This film essentially laid the basic groundwork for virtually EVERY wuxia film that would ever follow in its wake, from its pacing, setpieces, visual effects language, character dynamics and countless other storytelling tics...

…so of course, like so very, very many other early films of the Silent era, it remains tragically lost to time and is presently all but impossible to see anywhere with no known prints currently located. All that remains are still images and various scattered pieces of information and apocryphal trivia from various interviews, historical accounts, and production notes.

Another notable early Silent Wuxia film that DOES still exist however is 1929's Red Heroine. Telling a very standard, rote murder-training-revenge arc (that would of course become an all too familiar stock cliché in this genre), the titular Red Heroine is a young peasant girl named Yun Ko (played by then-popular Chinese actress Fan Xuepeng, who would become in the wake of this film one of the first ever Wuxia stars) who begins the film an average innocent young lady whose village is raided and sacked by a corrupt warlord general. Her kindly old grandmother ruthlessly murdered in the attack and her hapless scholar cousin unable to protect them, Yun Ko is captured and taken to the general's fortress to be made a sex slave in his harem.

Before she can be violated by the general's men however, she's rescued and taken away by an old hermetic (read: Xian) monk by the name of White Monkey who of course is also a great Wulin martial arts master. White Monkey takes Yun Ko under his wing as his student and trains her in the supernatural martial arts. By the end of her 3 years of training, Yun Ko is a master fighter capable of flying, teleporting, and other great feats of superhuman strength, allowing her to return to the general's fortress and wreak bloody revenge upon the evil marauding army.

(Yun Ko soars into battle)

As primitive and rudimentary as most Wuxia of the silent film era may be to modern viewers, these were obviously monumentally popular and groundbreaking films of their time period, bringing to vivid life for the first time ever ancient myth and folklore of Chinese culture only previously imagined in ancient writings, literature, and on the stage.

Indeed stage plays and Chinese opera performances were the closest that Wuxia had to be visualized prior to the advent of film, hence most all of the earliest ever Wuxia films (within and even for some time after the silent era in the early “talkies”) make extensive use of stage performance tricks and choreography for their action sequences, including EXTREMELY rough wirework for flying, puffs of smoke from the ground for “teleporting/materializing”, and hand to hand choreography that is more akin to stylized dancing than visceral combat.

The most cutting edge technological advancement used in the earliest Wuxia films was hand drawn rotoscoped animation for visually represented Ki techniques. These were an absolute marvel to Chinese audiences in the late 1920s when Burning of the Red Lotus Temple first made extensive use of it, and rotoscoping would continue to be the principal means of achieving the effect of Ki auras, blasts, and other assorted magical martial arts trickery throughout much of the entirety of live action Wuxia filmmaking for a great many decades all the way up until the advent and use of CGI became increasingly commonplace during the latter half of the 1990s.

In a serendipitous bit of cultural foreshadowing (which we'll get to the payoff of momentarily) the early silent era Wuxia landscape tended to be an extremely populous-driven film movement, with the genre most loved and consumed by audiences of poorer, lower class backgrounds.

As can be seen just in certain elements of Red Heroine as just one example, there was a hint of lurid pulp and exploitation prevalent in many Wuxia films, along with the general running anti-authoritarian/anti-establishment themes that come with stories focusing on a staunchly individualistic, authority-shirking warrior caste such as the Xia/Youxia, as well as the common Wuxia subtext promoting the individual's accomplishment, talent, and self-improvement over that of collectivist/conformist thinking.

This did not sit too well with the then-first emerging Communist Party of China, who early on saw these sorts of films as threatening, rabble-rousing among the masses, and promoting ideas diametrically opposed to that of Communist principals, making early Wuxia films for some years frequent targets for government raids, confiscation, and banning.

Combined with a general carelessness towards film preservation during the silent era as an overall whole and the easily decaying nature of early film stocks, and it unfortunately makes a GREAT deal of the early silent era of Wuxia films tragically, heartbreakingly lost forever to time, with only a relatively RARE select few films still surviving today.

This hostile attitude towards populist Wuxia films by the government would lax a tremendous deal after the Chinese Revolution of the late 1940s, which saw the creation of what we've come to know since as the People's Republic, as well as the 2nd assimilation of Hong Kong into Great Britain (Hong Kong being where a GREAT deal of Chinese films, martial arts/Wuxia and otherwise, are generally made). All just in time for the talkie (and soon later, colorized) era of film coming into being, along with far better standards for film preservation in general.

The 1950s would be another banner decade for 20th century Wuxia within an entirely different medium. The 50s saw a MASSIVE resurgence in popularity of Wuxia novels and literature, primarily launched by the absolutely monumental success of seminal and legendary Wuxia author Dr. Louis Cha (better known by his pen name, Jin Yong).

(Dr. Louis Cha, aka Jin Yong, indisputably the single most influential and prolific Wuxia writer of the last 60 years.)

Throughout the better part of the 1950s Dr. Cha would pen an absolutely staggering number of some of the most indispensably important Wuxia tales that would come to define the genre in its modern day context, including the Condor Heroes trilogy (Legend of the Condor Heroes, Return of the Condor Heroes, and the earlier mentioned Heaven Sword and Dragon Sabre), the Smiling Proud Wanderer series, Demi-Gods and Semi-Devils, and far, far too many more to list.

Many of Dr. Cha's novels are still to this day routinely adapted in an unbelievable array of adaptations spanning film, television, radio, animation, comic books/manhua, video games, and the stage, putting his stories easily in the same league of ubiquity as some of the most ancient and time honored Wuxia myths from the genre's ancient origins. Without his contributions, its entirely fair to say that the Wuxia genre's modern day landscape would've been a VASTLY different entity entirely.

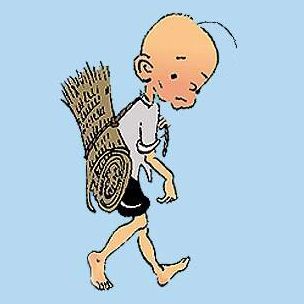

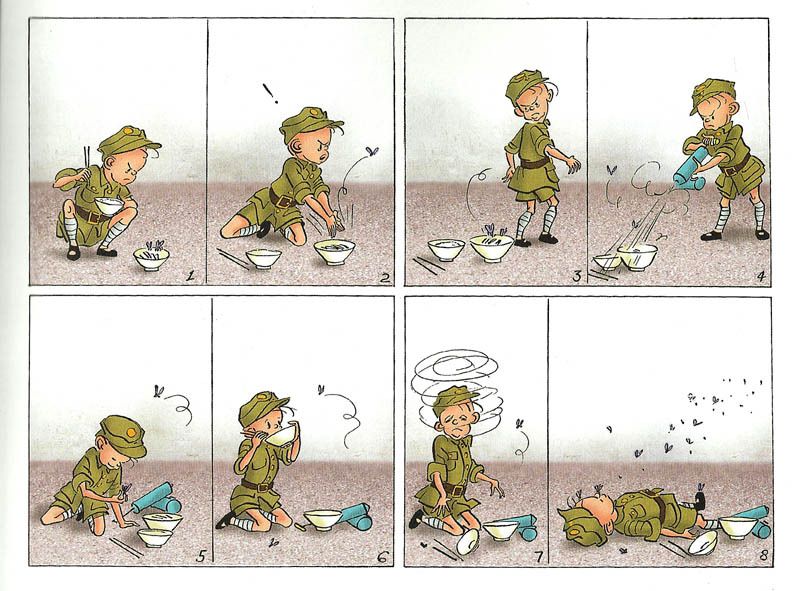

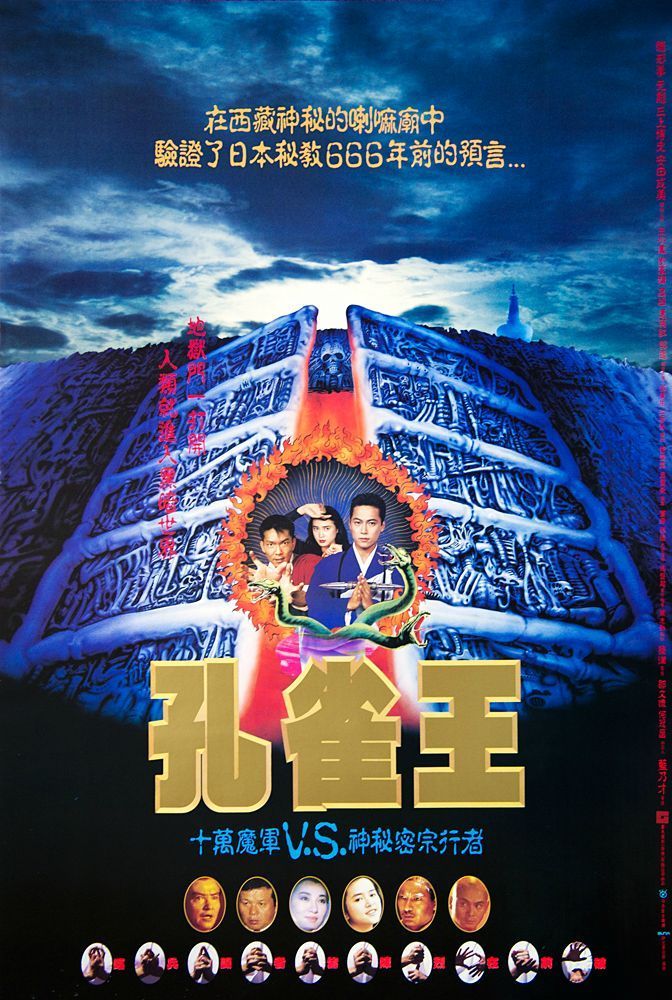

(The Wuxia stories of Louis Cha have invaded every square inch of media for the last 60 years. Pictured above are a sampling of different individual adaptations just for solely Legend of the Condor Heroes alone.)

Other notable Wuxia novelists would also come about during the 50s, including Gu Long, Liang Yusheng, and Sima Ling, making the decade generally seen as the defining golden era for modern literary Wuxia.

Back on the film end of things, more Wuxia talkie serials would be made throughout the 1950s and early 1960s (the first ever film adaptation of the Buddha's Palm mythos being a significant one), until the advent of a significantly HUGE player in the Chinese filmmaking world (particularly that of martial arts and Wuxia films): Shaw Brothers Studios.

Cue the fanfare...

Founded by brothers Runje, Runme, Runde, and Run Run Shaw, the impact of Shaw Bros. Studios on the martial arts filmmaking landscape is utterly impossible to succinctly summarize. A juggernaut that utterly and indisputably DOMINATED the martial arts filmmaking landscape throughout Asia all throughout the 1960s and 1970s, Shaw Studios was a well oiled machine that cranked out literally dozens upon dozens of films a year at their apex. The vast overwhelmingly majority were martial arts films, but they would also dip into other genres as well, including horror, romance, drama, and even at one point Tokusatsu (seriously).

Their only truly significant competition, which first came about in the early 70s, was Golden Harvest Studios, who would be for some years the only major Chinese film studio - also specializing heavily in martial arts films - to successfully hold their own against Shaw Studio's dominance. Indeed during the 1970s (a famously banner decade in general for Chinese martial arts cinema), they were effectively “The Big Two” of kung fu filmmaking, effecting an almost Marvel vs DC Comics/Nintendo vs Sega-like rivalry.

Does this remind you of anything?

A major difference between the two studios however (particularly more so in their earlier years) was their treatment of and attitudes towards Wuxia. While Shaw Brothers produced a TREMENDOUS number of incredibly outlandish and over the top wuxia films alongside their more grounded, straightforward martial arts films, Golden Harvest early on identified themselves as the more “grounded, gritty, realistic” alternative, and who - while still producing a certain amount of them - overall substantially downplayed Wuxia within their overall output in favor of much more (comparatively speaking at times) realism-rooted kung fu films.

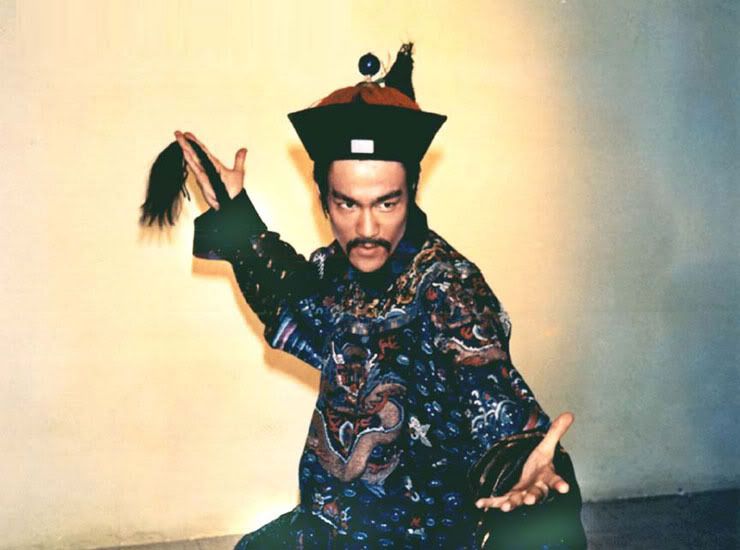

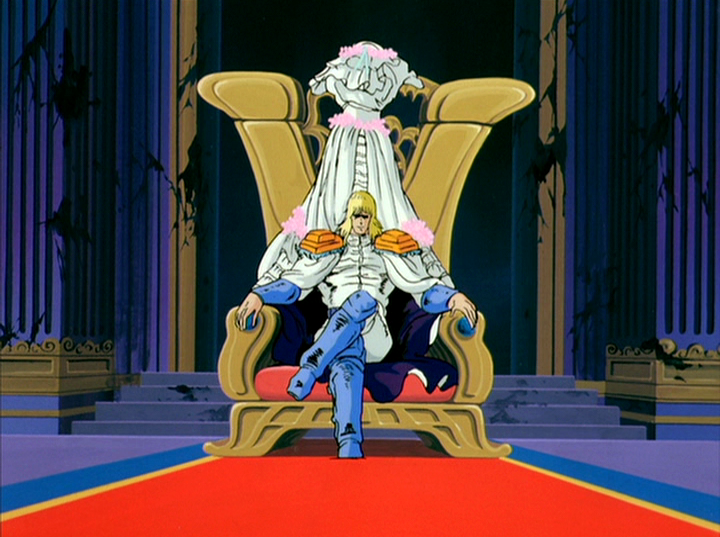

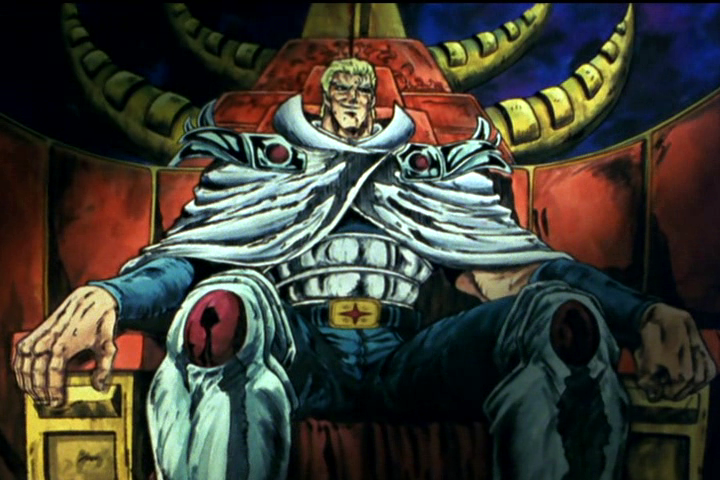

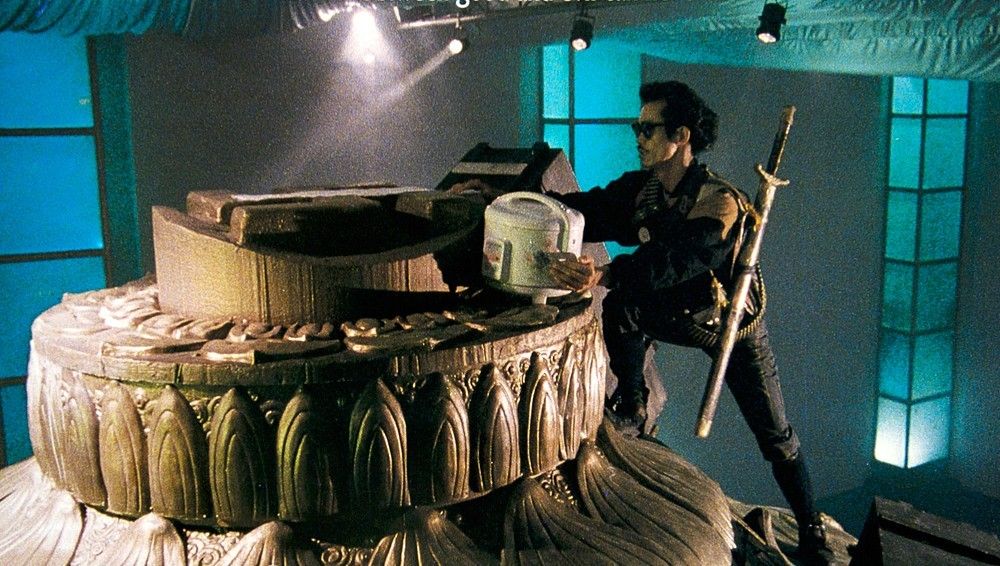

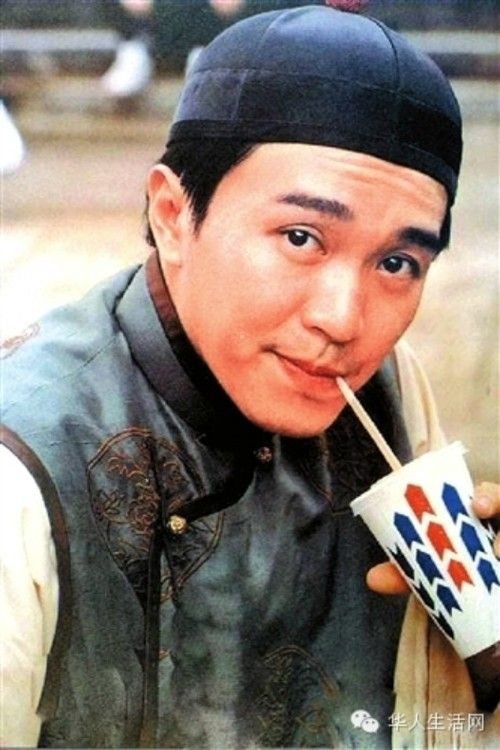

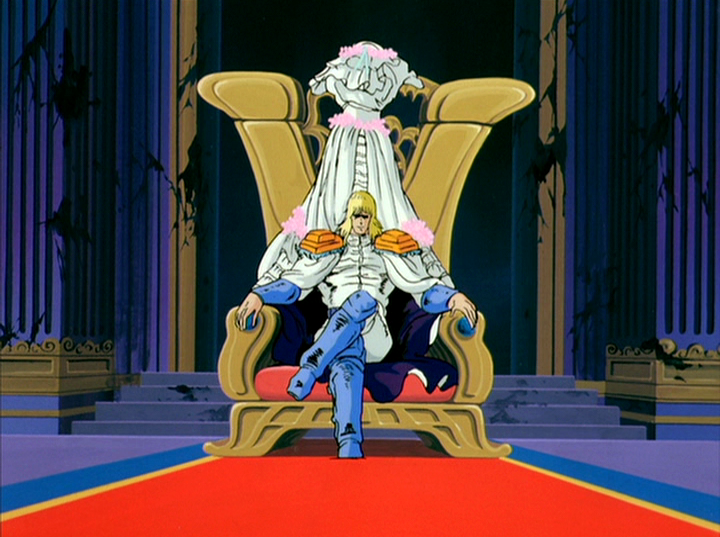

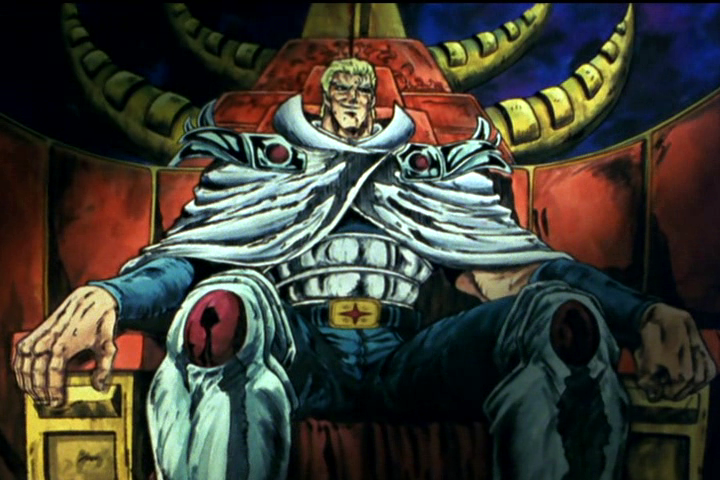

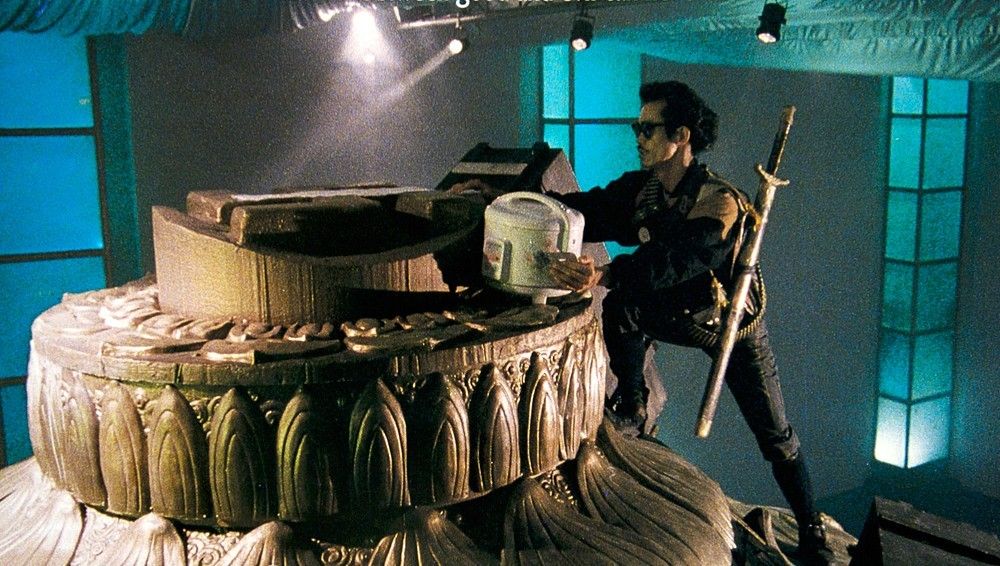

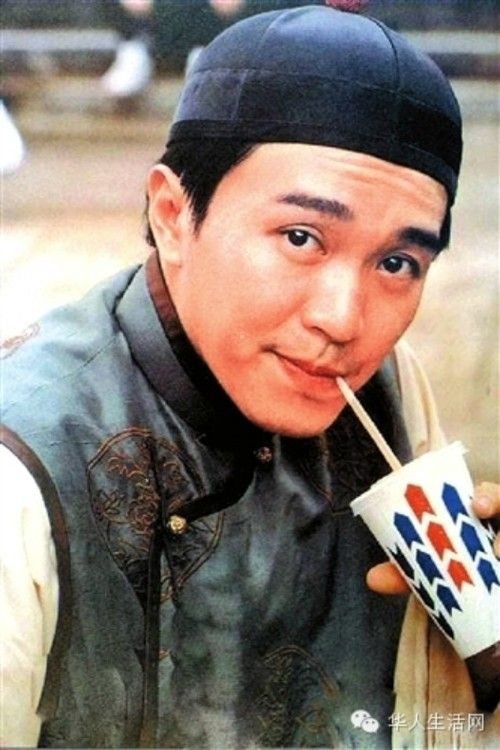

Legend has it that this was a significant factor in Golden Harvest scoring one of their most crippling long-term victories over Shaw Studios in the 70s: their signing of a certain martial arts performer by the name of Bruce Lee, who was quite famously not a very big fan of Wuxia (indeed at times a rather outspoken detractor of it) and greatly preferred more grounded in reality martial arts filmmaking. Images have floated around for years of Lee, during the period where Shaw Studios were still attempting to court him away from Golden Harvest, being costume fitted for various potential Wuxia roles, which Shaw generally made mandatory to all their actors: something which likely did not please or excite him too much.

(What could have been: Lee as a stuck up, pompous Mandarin scholar who learns mystical kung fu and becomes an embittered, badass villain/anti-hero of the Wulin world? Admit it, you want a peak into the alternate reality where that movie actually happened.)

Of the many, countless reasons for why Bruce Lee was a Big Goddamned Deal in the world of martial arts cinema (which you can easily read and view untold decades worth of writings and documentaries on the subject) was an especially HUGE leap forward in the evolving of martial arts filmmaking and on-screen fighting that he, and Golden Harvest in general, where largely responsible for.

A stickler for naturalism and a staunch forward-thinking progressive (hence a big part of his dislike of Wuxia: Lee found the genre hokey and rooted too deeply in the past, traditionalism, and increasingly out of date martial arts filmmaking principals, and thus saw them as a negative, discrediting factor in the rest of the world outside of Asia taking Kung Fu cinema seriously), Lee was among many other things a trailblazer and pioneer of breaking on-camera martial arts choreography away from the stiff, dance-like choreography of Peking Opera plays, and instead bringing a previously unheard of level of naturalism and realism to how the fights felt and came across.

This would, gradually and over time, revolutionize how ALL martial arts fighting would be depicted on camera. While many Golden Harvest performers, choreographers, and stunt people would quickly adapt to and embrace this incredible new form of fight choreography, Shaw would for a great many years remain stubbornly resistant to it. Beyond giving Golden Harvest a distinct identity apart from the then-towering juggernaut of martial arts cinema that was Shaw Studios (and thus allowing them to compete directly against them in ways that other studios struggled to), this would of course inevitably over time bite Shaw Bros. in the ass in other equally BIG ways... but we'll get to that shortly.

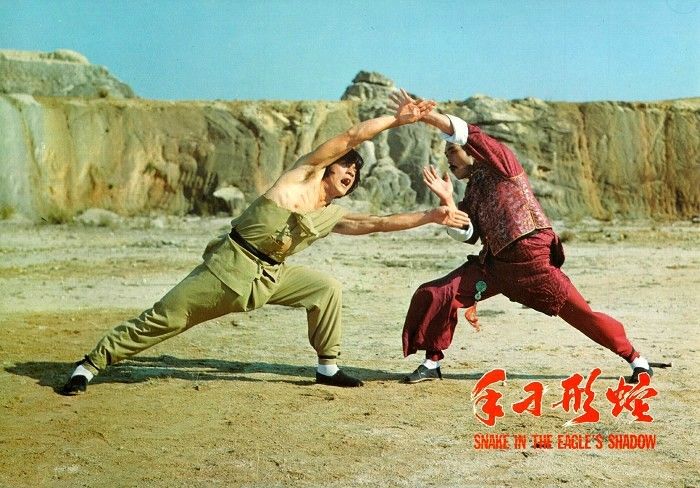

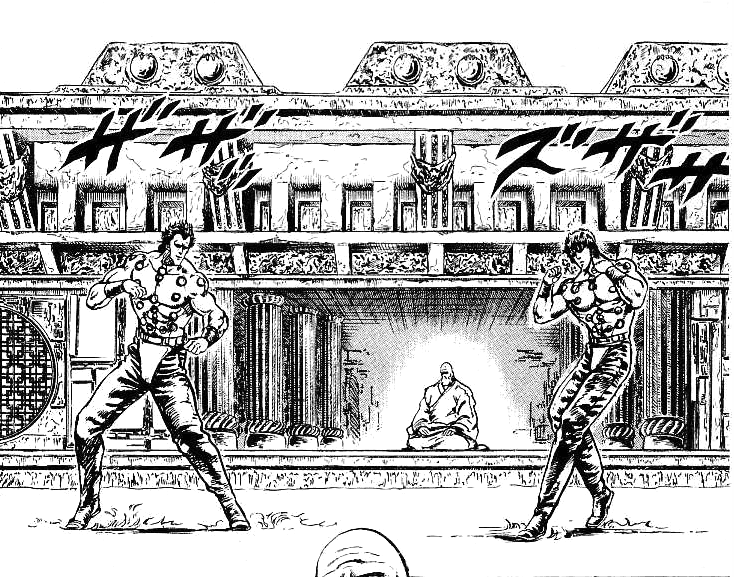

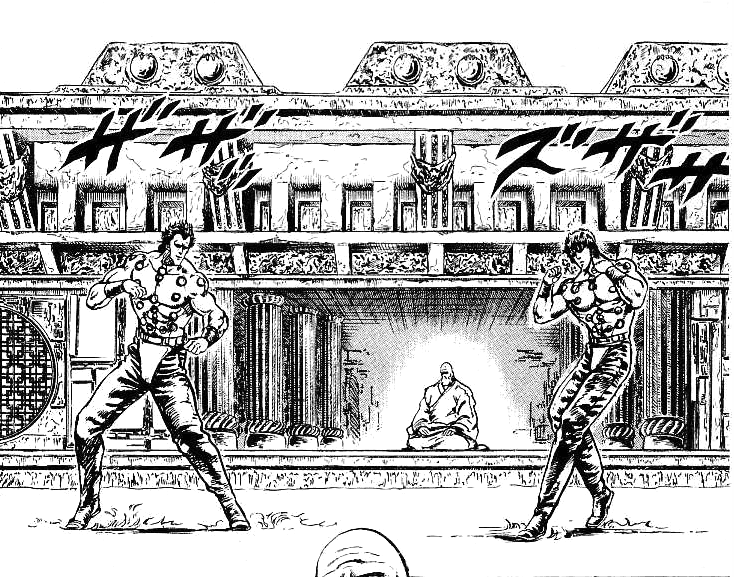

(Old school vs new school. On the left: stilted, stage-like left, right, left, right! One, two, three, four, one, two, three four! On the right: silk-smooth movement, a sense of unpredictable spontaneity, and gritty viciousness. As early as the dawn of the 70s, Lee was truly ahead of the curve.)

With Lee as the front and center-most superstar in Harvest's corner, other talents would emerge from the upstart studio to rival Shaw's stable of performers, including Carter Wong, Hwang In-Shik, Angela Mao (probably one of the all time most beloved and iconic female martial arts superstars who ever lived and one of my childhood heroes), and of course the incredibly charismatic and impossibly skilled Hwang Jang Lee (another martial artist who I positively worshiped for my entire adolescence).

All would star in numerous martial arts films that were often hard-edged, gritty, more grounded counterpoints to Shaw's overall larger fixation on ancient Chinese Wuxia lore and over the top stylized mystical martial arts fighting and tropes, with Golden Harvest as a studio only comparatively rarely venturing into Wuxia themselves (and certainly never with Bruce Lee's participation natch).

Nonetheless, even with the more relatively down-to-earth Golden Harvest as a constant ever-present thorn in their side, Shaw Brothers were for a few decades THE face and voice of Wuxia in Asian filmmaking. The sheer staggering number of films they produced in Wuxia alone (much less all their other genre endeavors) defies comprehension, many of which remain influential, stone cold classics to this very day.

Timeless classics Golden Swallow and Come Drink With Me, adaptations of Water Margin and Journey to the West, The Magic Blade, King Boxer, One-Armed Swordsman, Fist of the White Lotus, Five Deadly Venoms (introducing to the world the Venom Mob, a troupe of incredibly charismatic, versatile, and well-liked martial arts actors), the nearly-lost gem The Black Tavern, Have Sword Will Travel, Temple of the Red Lotus (Shaw's own remake of the above-noted lost silent classic The Burning of the Red Lotus Temple), and of course their defining crown jewel 36th Chamber of Shaolin... Shaw's output is among the most rightly celebrated and beloved in wuxia (and just general martial arts, which I barely even touched on above) film fandom, more than justifiably so.

(One of the most towering legacies in all of martial arts film history.)

Countless superstar names in kung fu filmmaking would come out of Shaw studios, from directors Chang Cheh and Lau Kar-Leung - both responsible for a vast majority of Shaw's best films, with Cheh in particular also becoming notable for often blending the fanciful silliness of Wuxia with harsh, graphic violence and gore...

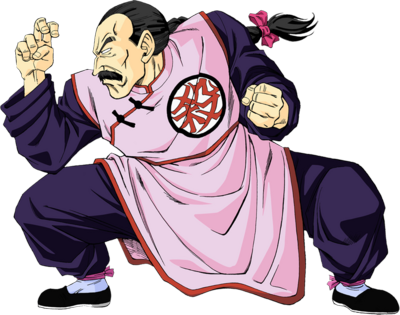

...as well as instantly iconic on-camera talents like Lo Lieh, Jimmy Wang Yu, Kara Hui, Wang Lung-Wei, Cheng Pei-Pei, Ti Lung, the tragically gone-too-soon Alexander Fu Sheng, the aforementioned Venom Mob (including one of my personal all time favorites, the disgustingly talented Philip Kwok), and of course the one and only great himself, Gordon Liu (the overwhelmingly most likely candidate for the principal basis of Kuririn).

While there were certainly some stray, but no less immensely notable martial arts and Wuxia films made outside of either Shaw Bros or Golden Harvest - particularly by the great King Hu, who made wuxia movies for BOTH studios, as well as outside of them entirely: A Touch of Zen and the original Dragon Gate Inn (two of the all time greatest Wuxia films in history) were notably made by Hu without either Shaw or Harvest, as well as some very notable Taiwanese-produced indie kung fu films – overall the 60s and vast bulk of the 70s were indeed the golden era of Shaw.

Many more modern martial arts/wuxia filmmaking staples would evolve and grow to prominence thanks largely to Shaw, from atmospheric, Spaghetti Western-like foreboding pacing and tension building (your pre-fight “drawn out staredowns” and the like), as well as their instantly iconic and distinctive style of musical scores (traditional Chinese orchestral, very brassy and with just a hint of 70s funk): and for Westerners of course, the horrendously, gloriously bad dubbing.

Wuxia in Modern Media Section II: The Grindhouse Years – First Crossover Success in the Western World (1970 - 1979)

Speaking of Shaw's (and Harvest's) impact on us Westerners, I'd be remiss if I didn't point out that end of the equation. Over in America during the late 1960s and throughout 1970s (and 80s even) there was a growing new venue for film viewing known colloquially as the Grindhouse Theater.

Some of you may have heard the term in more recent-ish years thanks to constant stumping/promoting of it by the likes of Quentin Tarantino, but for those of you who are still completely oblivious to such things, I'll explain (as this is CRUCIALLY important to the topic anyway).

Grindhouse Theaters were low rent, often incredibly filthy, scummy, decrepit shithole little movie theaters that largely operated in major urban cities (particularly in New York). Generally found in the poorest, most dangerous and crime-ridden areas, Grindhouse Theaters were as FAR from mainstream viewing as you could conceivably get.

Specializing in showing amorally exploitative films (from rape films, to nun fetish movies, chainsaw slasher killer films, biker thug epics, and straight up porn of the vilest, sickest kind) to an audience of (certainly not always, but very often) junkies, trench coat-wearing perverts, and random street weirdos, Grindhouse Theaters were the kinds of places where the skeevy, mangy, leering creep you hope to never run into while walking home alone through the scary part of town late at night might head off to to kill time and relax.

So... what in the atomic powered fucking hell could something like THAT of all things have to do with Wuxia? Plenty.

You see, apart from the sick, twisted shit they were most known and infamous for, Grindhouse Theaters specialized in showing a pretty diverse array of other things as well. As their general choice of locations would denote, Grindhouse theaters were businesses of EXTREMELY limited budget and means. They wouldn't show your average, mainstream, A-list features not only because the sort of clientele they catered to would likely not hold the slightest interest, but also because they straight up often couldn't AFFORD the damn film prints even if they actually wanted to show them.

The film selection of a typical grindhouse theater was as much borne out of economic necessity as it was the incredibly fucked taste of the audiences: these were cheap, dingy theaters located in poor, dingy neighborhoods, and they got exactly the kinds of cheap shit that they could afford to get: and these films were largely so cheap to get in the first place because no self-respecting mainstream theater in the “straight-laced, proper” parts of town had the slightest interest in showing them. Some were crazed indies made by utterly bonkers eccentrics, but others were also Mafia funded: but that's an entirely other story unto itself.

Grindhouse theaters were thus a foster home to the unwanted bastard, deformed, abandoned freaks of the cinematic world. So of course this would include things like scat porn and movies about genital mutilating cannibals and sexually maladjusted serial killers who fuck homeless people to death with power drills.

(Oh yes, that's an ACTUAL grindhouse movie too.)

BUT... grindhouse theaters were also a viable venue for OTHER extremely diverse, fascinating curios besides those.

I doubt I'll be shocking anyone when I note that mainstream America in the 1970s was still a pretty great deal culturally xenophobic. It took a foreign filmmaker of IMMENSE artistic prestige (a Jean-Luc Godard type) to get their stuff seen and appreciated by an American public that was even halfway close to mainstream back then (like say, a college campus-type crowd). Any regular old pulpy genre effort coming from overseas usually had about a snowballs chance in hell of ever getting shown in a regular American theater in mom & pop middle American suburbia, no matter how well made or legitimately interesting it might otherwise be.

Thus grindhouse theaters would often step in and purchase prints for all sorts of hugely interesting (and absolutely bonkers bizarre) foreign movies to further pad out their nightly showings of gore, tits, and sleaze. Spaghetti Westerns and arty giallo thrillers from Italy (that walked a VERY fine tightrope balance smack in between legitimately elegant and classy as well as luridly filthy and skeevy) were among the favorites, but also among them was... Chinese kung fu films. Both standard kung fu and supernatural Wuxia.

(Come for the gang-rape and gore-porn, stay for the silly-fun antics of ancient Chinese Kung Fu mystics flying about.)

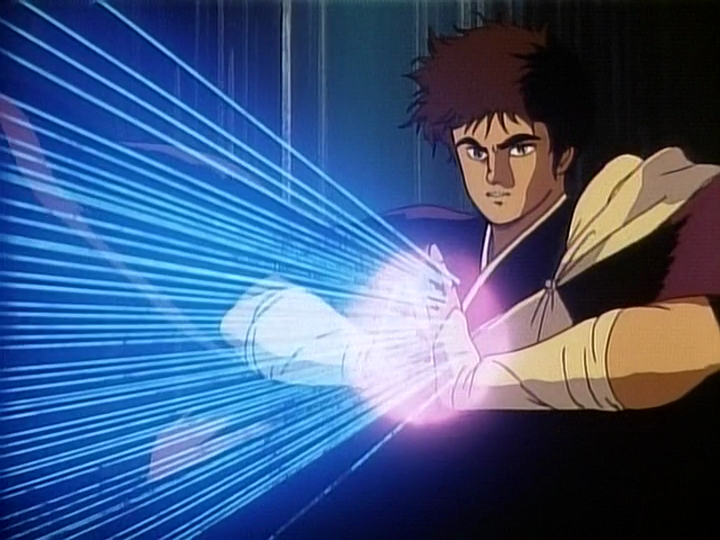

So it was that, as much of a shock as this may come to some folks here, the martial arts/Wuxia genre gained its very first ever true burst of popularity and exposure in North America in the 1970s primarily from the same cesspit theaters that also heavily trafficked in the grossest, most vile and taboo cinematic sewage that crawled from the 70s exploitation circuit. Your average round eyes of the 70s probably got their first ever glimpse of Ti Lung or Lo Lieh flying around on wires and firing mystical laser beams from their fingertips at Chinese demons from the same double bill showing where they could also see an actual real life medical cadaver getting eyeball-mutilated in loving closeup in They Call Her One Eye.

Wuxia and Grindhouse cinema in fact actually have a very tight history/relationship with one another in the U.S. that spans at least a couple of decades (70s and 80s).

Shaw Brothers' King Boxer (shown in the Grindhouse Circuit under the alternate title “Five Fingers of Death”, which I've always personally preferred) was THE first ever smash hit Chinese Kung Fu film in America, largely preceding even Bruce Lee's crossover into more mainstream Western popularity. The success of King Boxer/Five Fingers of Death lead to a HUGE pouring over of CONTLESS kung fu and wuxia films in grindhouse venues across the country for a great number of years following; a great many of them Shaw Bros. and Golden harvest productions, complete with the legendarily terrible English dubbing that they'd largely become famous for for many, many decades down the line up to this day.

Aaaaaand cue that OTHER fanfare...

This as it turns out is also the origin of the immense popularity of martial arts films among black/African American culture. Black patrons were very commonplace in grindhouse theaters as they were located in a great many largely black ghettos in the 70s (hence Blacksploitation films, also a grindhouse staple). Of all the kinds of films shown in grindhouse theaters, Kung Fu and Wuxia films (apart from blacksploitation films at least) were BY FAR AND AWAY the biggest runaway success amongst black audiences.

Its not very hard at all to see why: remember the anti-authoritarian streak I talked about that ran in a lot of Wuxia? A tremendously great deal of Wuxia and Kung Fu films centered on strong, able bodied martial artists from often poor, rural communities that are under the boot-heel of a powerful, oppressive government/dictatorship. Often the hero would rise up against the oppressive warlords in the name of their village and, with little more than raw fiery righteous anger and talented skill, would knock said-oppressive tyrannical warlord/authority figure down a few pegs with a sound ass-whipping.

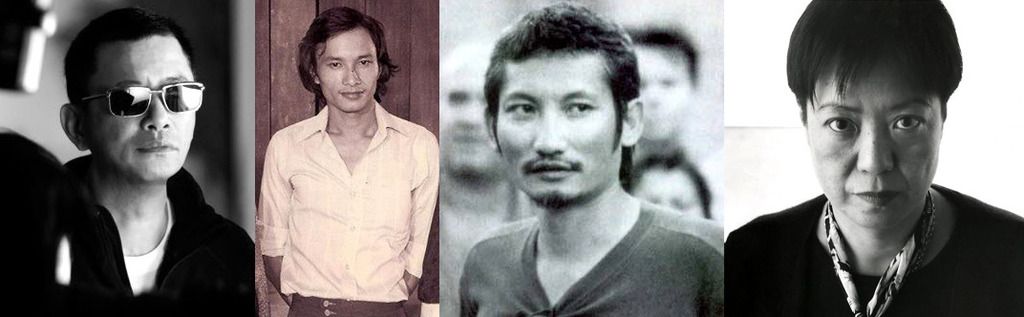

(On the left: martial artist/actor Jim Kelly personified the massive overlap between Kung Fu cinema and black grindhouses in the 1970s. On the right: rapper and founding Wu Tang Clan member RZA has taken up that mantle throughout the 1990s and 2000s, acting as one of the biggest celebrity fans/proponents for martial arts fiction and Wuxia to the point of offering vastly knowledgeable and insightful commentary tracks on DVDs/Blu Rays for a number of older classic Wuxia films and recently directing a Wxia film of his own, The Man With the Iron Fists.)

If you know a DAMN thing about black history in the United States, particularly pertaining to life in the slums/hoods, the appeal of these kinds of films to poor black audiences should be STRIKINGLY apparent. This would of course transfer over into hip hop culture as well once that came into being in the 80s. This is the very wellspring from which you get hip hop groups like the Wu Tang Clan and so forth (which now you also know from earlier where even THAT name originates from). In many respects, this closely mirrors the original appeal that the earliest silent Wuxia films had with lower class, poorer Chinese audiences in the 1920s (and which the then-still rising Communist government saw as a threat).

(Fun fact: “Legend of the Liquid Sword” is as it turns out the title of a Wuxia movie, which is where the iconic GZA album in turn takes its title from. Its a pretty cool flick too.)

This would thus mark the earliest beginnings of Wuxia and martial arts fiction in general creeping its way Westward out of Asia and into American pop culture. And not long after Bruce Lee would find massive crossover fame in mainstream America, thus bringing the popularity of martial arts cinema further out of the black ghettos and into the straightlaced middle class white world.

However as noted, Lee wasn't particularly fond of Wuxia, and kept his (tragically short) output completely relegated to grounded, non-mythical-bsed kung fu. As Lee was for the time THE mainstream face of Asian martial arts cinema to regular Americans (and indeed the primary driving force behind its sudden explosion in wider popularity), standard, non-mystical kung fu was what most of the non-grindhouse-patronizing Western mainstream was left familiar with.

Lee was also signed with Golden Harvest, who as I noted were FAR less reliant upon Wuxia than Shaw was at that point, and indeed were at the time much better known for their more reality-based (and often quite 70s gritty), decidedly non-fanciful kung fu films: thus the overall Golden Harvest style was far better known in the 70s to mainstream American viewers than Shaw's more outlandish magic and myth-based kung fu films.

Nonetheless the metaphysical zaniness of Wuxia had still indeed made its mark here in the U.S., but it was largely relegated to the underground, the niche, hardcore nerds, and the sleaze pit theaters in the sleaze pit parts of the big cities.

Still, it would crop up from time to time in various Western outlets such as Marvel Comics when in the mid-70s they created Shang Chi, Iron Fist (their own resident Wuxia-themed superhero), and the mystical hidden lands and city of K'un-Lun (Marvel's own rough approximation of Jianghu, a magic hidden area of China where all manner of Wuxia lore is real).

The single most famous example of elements of Wuxia lore popping up in a piece of mainstream Western media during this time period, without question, is of course the original Star Wars trilogy. That Star Wars is a total hodgepodge of disparate pulp influences, both domestic and foreign, has long been common knowledge. But amongst its morass of pulp film serial, WWII drama, space opera, heroic myth, and Chanbara/Jidaigeki (classic Samurai) influences is also Wuxia.

(A Flash Gordon Serial re-imagined with flourishes of Wuxia, Chanbara, Joseph Campbell, and WWII propaganda: Star Wars in its own way was a bit of foreshadowing of what was to come for Wuxia in its native land.)

Wuxia is in fact arguably among Star Wars' most integral influences, certainly at least when pertaining to the lore of the Jedi Knights: the Jedi themselves are just as purposefully reminiscent of Xia/the Wulin community as they are classic Samurai archetypes, and the concept of Chi/Ki as a universal life energy inherent within nature is at the heart of The Force, which is generally agreed to be one of the most fascinating and alluring elements of the original trilogy by most fans.

Not only does the Force closely mirror Ki at a basic conceptual level, but even in terms of how its portrayed on screen, via different sects and clans of characters being able to tap into it with hard training thus allowing them to use the power of The Force/Chi to “sense” one another through it as well as using it to mentally levitate objects and increase their own physical prowess to leap about with superhuman agility. Even Luke's famous training sequence on Dagobah with Yoda is directly reminiscent of the sorts of metaphysical kung fu training that most Xia undergo in a great many Wuxia stories.

Last edited by Kunzait_83 on Sun Jan 31, 2016 3:52 am, edited 3 times in total.

http://80s90sdragonballart.tumblr.com/

Kunzait's Wuxia Thread

Kunzait's Wuxia Thread

Journey to the West, chapter 26 wrote:The strong man will meet someone stronger still:

Come to naught at last he surely will!

Zephyr wrote:And that's to say nothing of how pretty much impossible it is to capture what made the original run of the series so great. I'm in the generation of fans that started with Toonami, so I totally empathize with the feeling of having "missed the party", experiencing disappointment, and wanting to experience it myself. But I can't, that's how life is. Time is a bitch. The party is over. Kageyama, Kikuchi, and Maeda are off the sauce now; Yanami almost OD'd; Yamamoto got arrested; Toriyama's not going to light trash cans on fire and hang from the chandelier anymore. We can't get the band back together, and even if we could, everyone's either old, in poor health, or calmed way the fuck down. Best we're going to get, and are getting, is a party that's almost entirely devoid of the magic that made the original one so awesome that we even want more.

Kamiccolo9 wrote:It grinds my gears that people get "outraged" over any of this stuff. It's a fucking cartoon. If you are that determined to be angry about something, get off the internet and make a stand for something that actually matters.

Rocketman wrote:"Shonen" basically means "stupid sentimental shit" anyway, so it's ok to be anti-shonen.

- Kunzait_83

- I Live Here

- Posts: 2974

- Joined: Fri Dec 31, 2004 5:19 pm

Re: Dragon Ball's True Genre: We Need to Talk about Wuxia

Wuxia in Modern Media Section III: The Hong Kong New Wave (1979 - 1987)

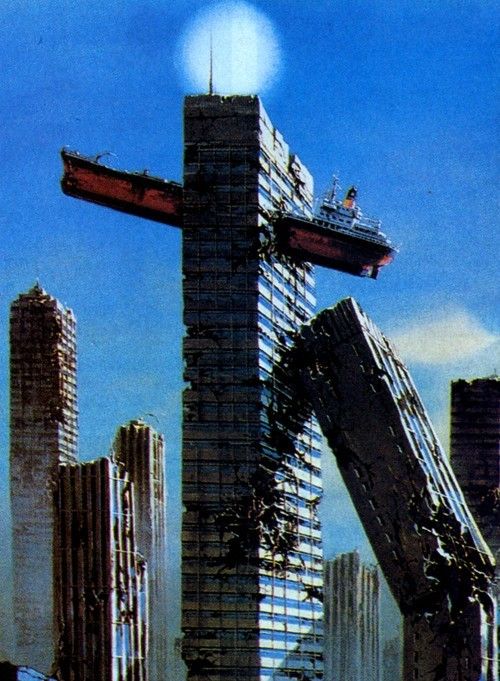

Moving our focus back to China for now though, by the late 70s and especially the early 80s, Shaw Brothers Studios was beginning to fall on hard times. There were a number of factors at work: chief among them was the financial strain of keeping such a massive fucking entity of a studio afloat for so long.

Shaw Studios was unlike any other movie studio before or since: cranking out so many movies within so short a time span utilizing a rotating roster of familiar cast and crew members across each movie, the studio was set up less like a traditional film lot and almost more like a small town or commune: many production crew members and even actors and stunt people would actually LIVE at the studio as their literal home for months, sometimes years at a time, bouncing in true workhorse-like fashion from one film project to the next in extremely rapid succession, sometimes with little to no breathing room in between.

(Birds-eye view of Shaw Studios circa the late 60s.)

By extension of this, there was over-saturation: by the end of their existence, Shaw had produced untold THOUSANDS of movies. Dozens would be put out every year: no mater how good the material, audience fatigue was inevitable.

As a consequence, Wuxia in particular was beginning to grow immensely stale and boring to Chinese audiences by the latter-end of the 70s. Telling and retelling and re-retelling many of the same old myths and legends on film in a very rigidly faithful fashion and with decreasing variation in style as time wore on, for a particularly bleak time in the late 70s Wuxia was starting to be seen in China as bland, predictable, and stuffy.

Part of it on Shaw's end was the sheer inertia of routine and the creative complacency that comes with success: due to how the studio was set up they were a well oiled machine, pumping out movie after movie after movie after movie in an almost assembly line-like fashion. Some degree of formulaic sameness was bound to overtake their output after awhile and audiences were getting wise to it; Shaw's box office fortunes began to sharply decline.

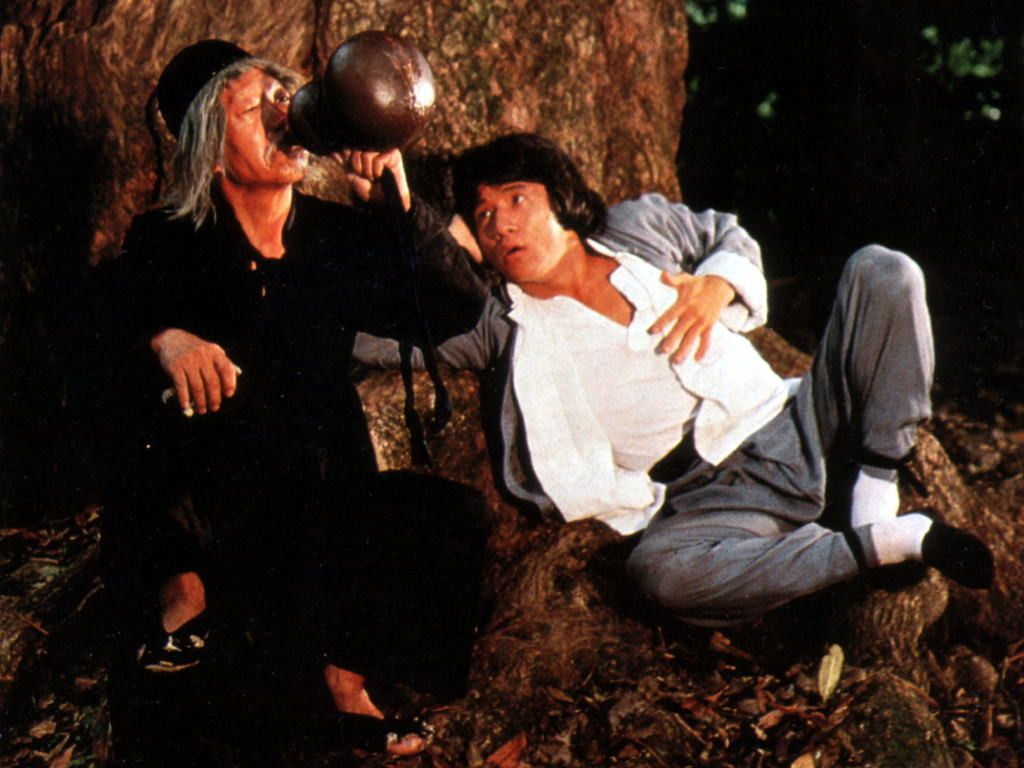

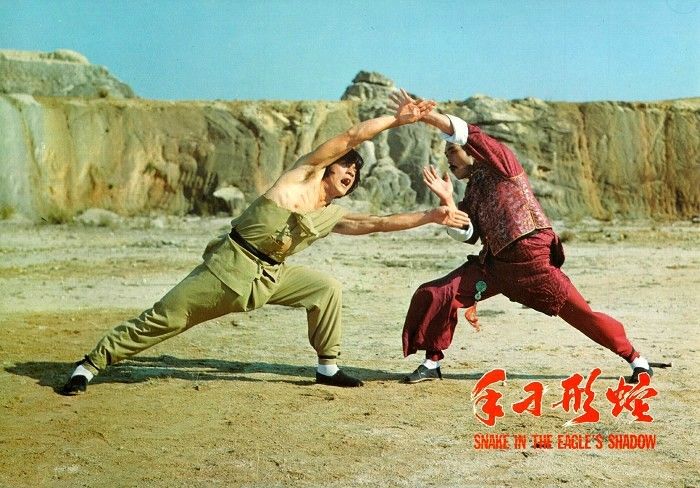

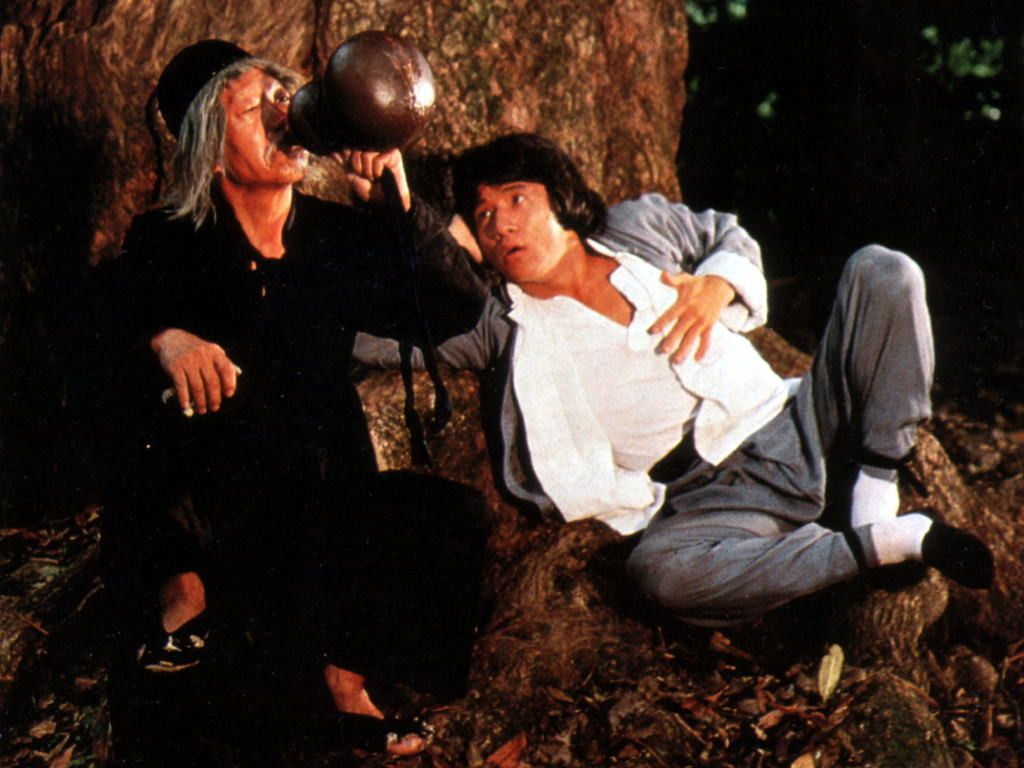

Meanwhile Golden Harvest were continuing to enjoy increased success. After Bruce Lee's tragic passing (which cut short the kung fu movie craze in mainstream/non-grindhouse America after a few years, at least for awhile), Golden Harvest would have the great fortune of stumbling upon another incredible find of a talent: a guy by the name of Jackie Chan.