Dragon Ball's True Genre: We Need to Talk about Wuxia

Moderators: General Help, Kanzenshuu Staff

- Kunzait_83

- I Live Here

- Posts: 2974

- Joined: Fri Dec 31, 2004 5:19 pm

Re: Dragon Ball's True Genre: We Need to Talk about Wuxia

I suppose not. S'what its here for.

EDIT: Oop! Third page!

EDIT: Oop! Third page!

http://80s90sdragonballart.tumblr.com/

Kunzait's Wuxia Thread

Kunzait's Wuxia Thread

Journey to the West, chapter 26 wrote:The strong man will meet someone stronger still:

Come to naught at last he surely will!

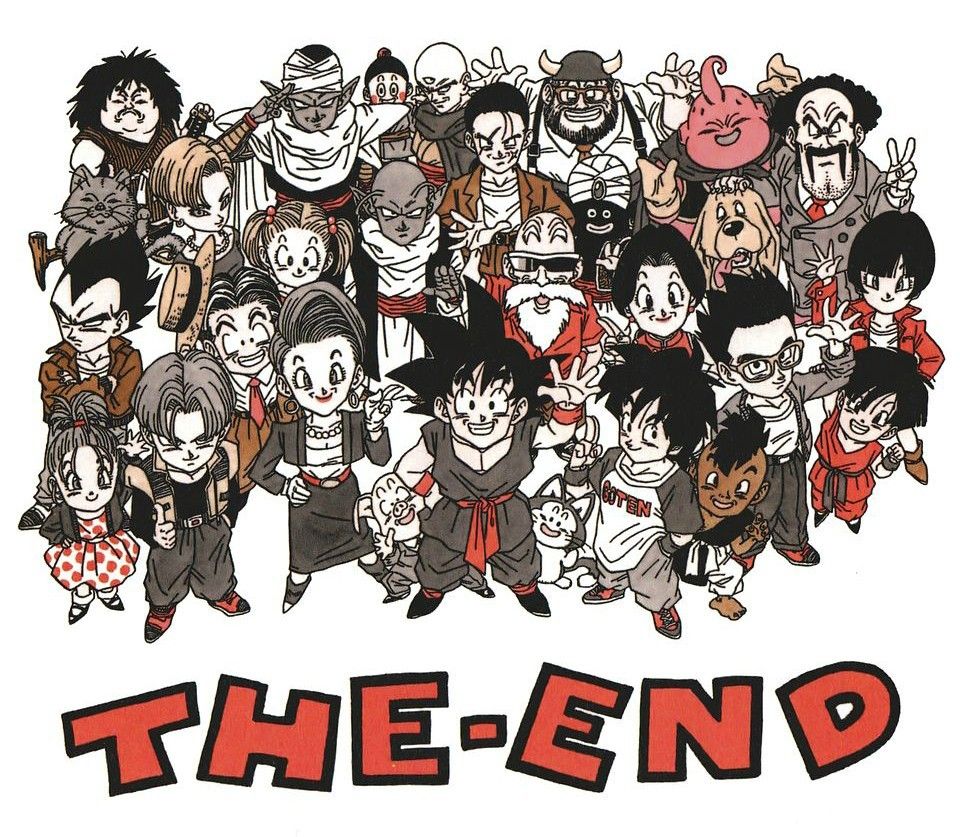

Zephyr wrote:And that's to say nothing of how pretty much impossible it is to capture what made the original run of the series so great. I'm in the generation of fans that started with Toonami, so I totally empathize with the feeling of having "missed the party", experiencing disappointment, and wanting to experience it myself. But I can't, that's how life is. Time is a bitch. The party is over. Kageyama, Kikuchi, and Maeda are off the sauce now; Yanami almost OD'd; Yamamoto got arrested; Toriyama's not going to light trash cans on fire and hang from the chandelier anymore. We can't get the band back together, and even if we could, everyone's either old, in poor health, or calmed way the fuck down. Best we're going to get, and are getting, is a party that's almost entirely devoid of the magic that made the original one so awesome that we even want more.

Kamiccolo9 wrote:It grinds my gears that people get "outraged" over any of this stuff. It's a fucking cartoon. If you are that determined to be angry about something, get off the internet and make a stand for something that actually matters.

Rocketman wrote:"Shonen" basically means "stupid sentimental shit" anyway, so it's ok to be anti-shonen.

- Kunzait_83

- I Live Here

- Posts: 2974

- Joined: Fri Dec 31, 2004 5:19 pm

Re: Dragon Ball's True Genre: We Need to Talk about Wuxia

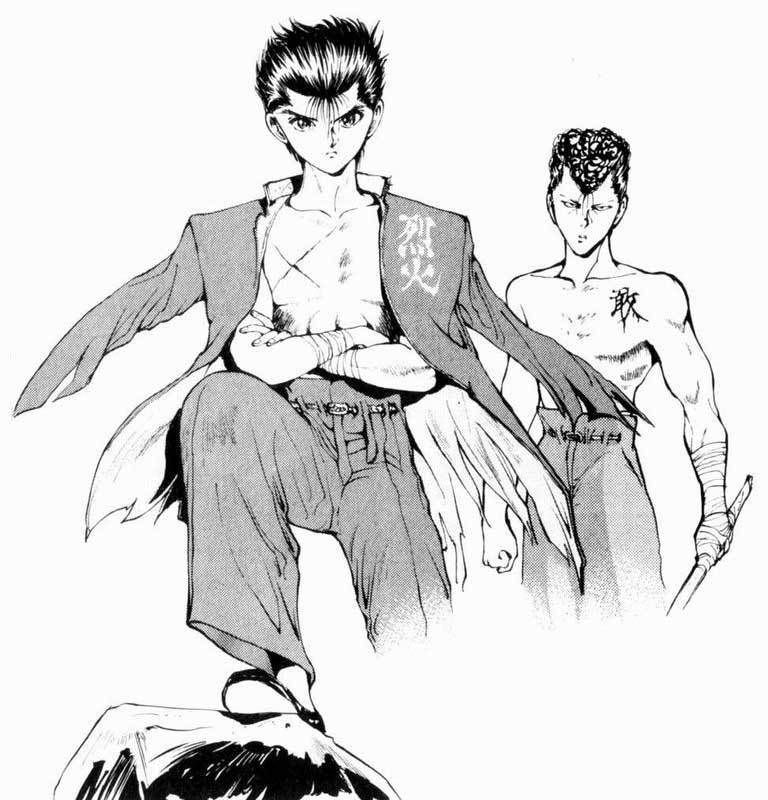

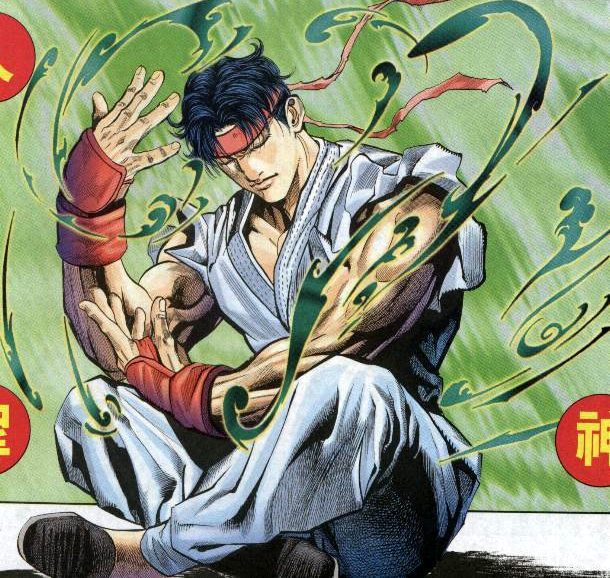

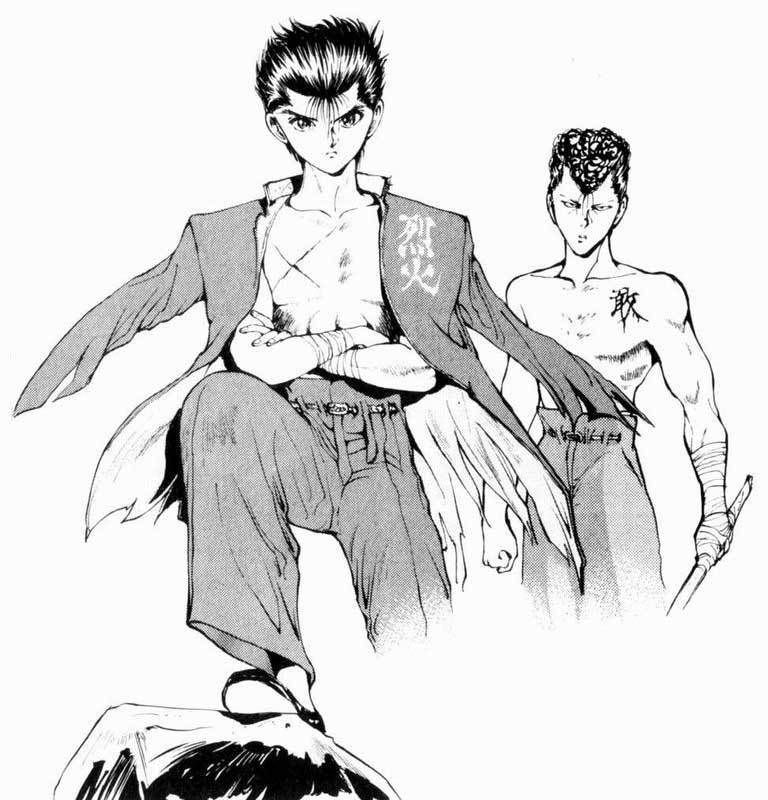

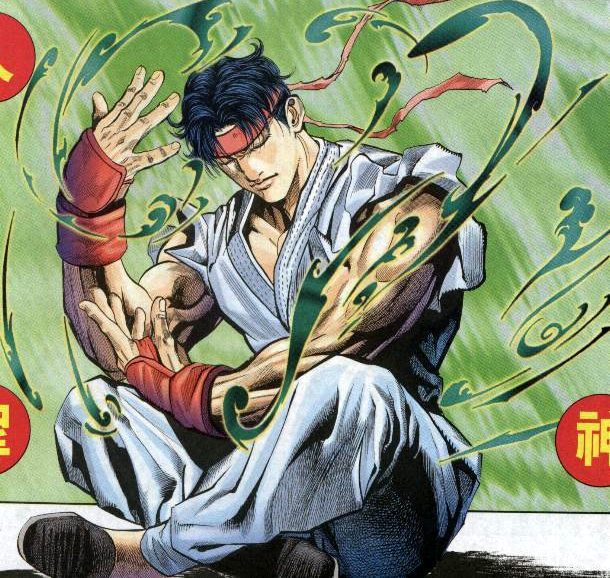

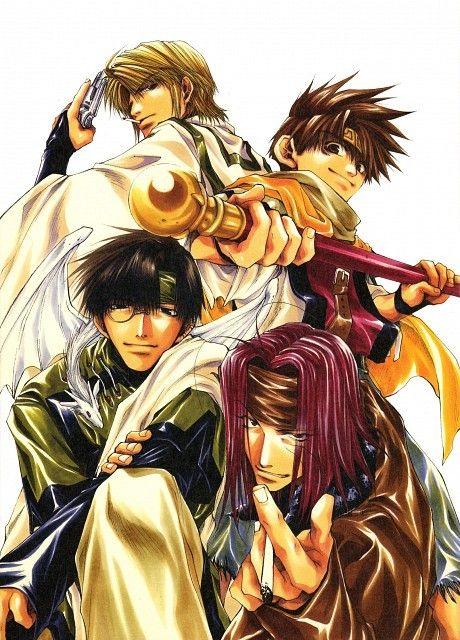

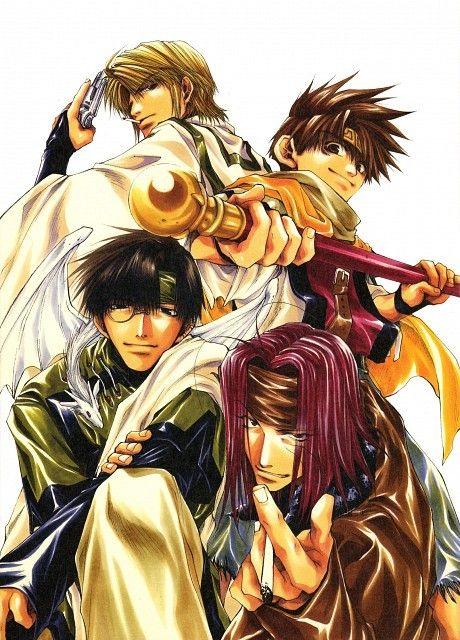

I don't think I have to say much to this particular crowd about Yu Yu Hakusho (thankfully). It ranks alongside DBZ as one of the defining Shonen Wuxia manga/anime mega-franchises of the early 90s. We'll just briefly run through and review the basics in light of all the previous info (and for the benefit of the few people here who may still be in the dark about this series as well).

So with YYH we've got a manga/anime series that's set in then-modern 1990s Japan, primarily focusing on Yusuke Urameshi and Kazuma Kuwabara, a pair of rival 14 year old middle school-age rebellious delinquent punks whose very immediate futures seem perfectly poised for a life of petty criminal thuggery and Bosozoku gang membership (and in Yusuke's case, judging by his strongly hinted-at family background in the manga, probably a future even further down the road of life as a Yakuza hood).

The fairly predictable path of youthful ruin for these two boys is completely derailed however when Yusuke is of course run down and killed by a speeding car while uncharacteristically saving the life of a small child within the very first manga chapter/anime episode and is revived as a spirit. Kuwabara not long after has his own latent ESP-like psychic connection with the realm of the dead awakened.

After Yusuke is resurrected by Koenma, son of the mythical Great King Enma (due to him dying before his intended time), he and shortly later Kuwabara are recruited by the Spirit World (afterlife) to be their agents in the Human World (Earth/the living world), investigating and combating incidents involving demons and evil spirits from the Demon World (Hell) running amok.

They're both also joined by Kurama and Hiei, a Fox Demon and Fire Demon respectively, who were both once criminals in the Spirit World and are forced by Koenma (after being apprehended initially by Yusuke) to work alongside Yusuke and Kuwabara as almost a form of spiritual/paranormal “community service”.

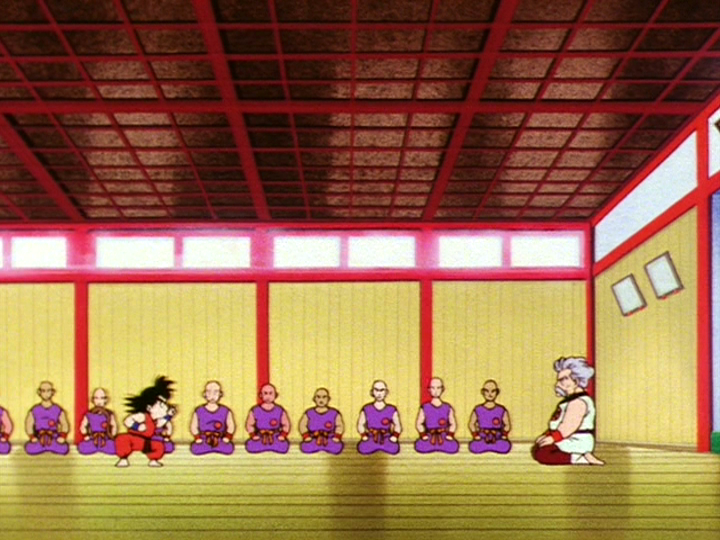

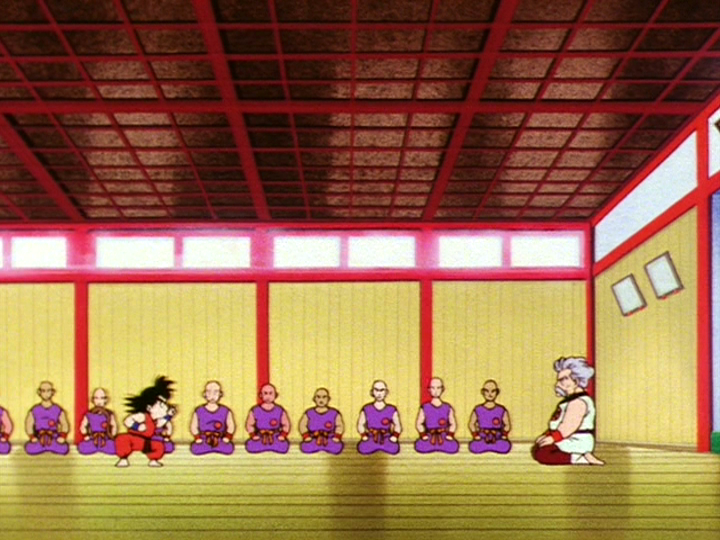

Before long however, the series' shifts its focus away from Yusuke's duties as a Spirit World Detective and more towards his, you guessed it, ever growing and evolving supernatural martial arts skills. Upon dying and being resurrected, Yusuke's mind and spirit are awakened to his latent ability to harness and focus his Ki, and he is mandated by Koenma to train this ability in the form of supernatural martial arts by the great master Genkai so as to be a more effective fighter against the demonic hordes he will be facing as a Spirit World Detective.

Among Yusuke's greatest opponents is Toguro, formerly Genkai's martial arts peer and lover, who sold his soul to become a demon so that he will never age or lose his strength as a martial arts master. Toguro becomes obsessed with and fixated on Yusuke's strength and power as a fighter, and his encounters with Yusuke further brings out in the boy his own Youxia-like will and ideals as a fighter to continue to grow and improve for the sake of growing and improving and realizing his own full potential, all the while with Toguro acting as a cautionary tale and tragic reminder of where those warrior's ideals for growth can lead when they completely and utterly consume a fighter to the point of total obsession.

Pretty much most all of Yusuke's major demonic martial arts adversaries throughout the series function in a similar manner to Toguro, acting as dark reflections of Yusuke's own Youxia-like tendencies and showing where they can lead him astray if he doesn't properly apply them and think the ramifications of his actions through clearly.

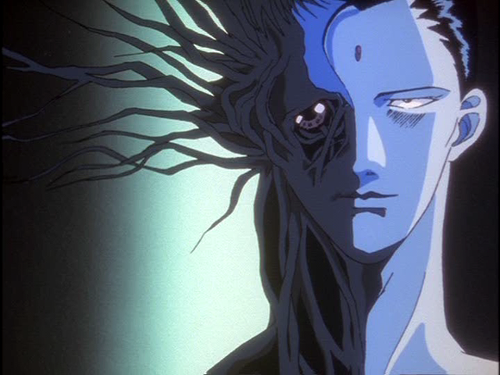

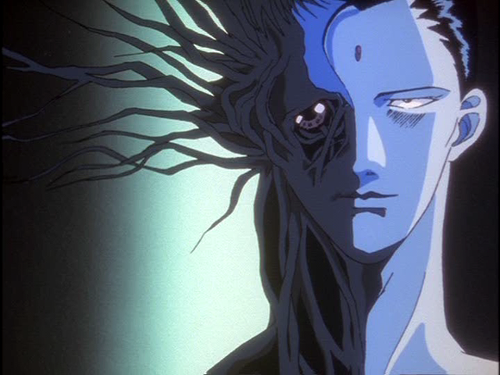

This is especially apparent in Sensui Shinobu, a once incredibly heroic Spirit World Detective and masterful martial arts warrior who was tragically driven irrevocably and murderously insane by the extreme corruption of the Human World and his own deeply held and unshakable moral and ethical principals as a warrior.

Yu Yu Hakusho is the very essence of early 90s post-modern/post-genre barriers Wuxia personified. You cannot get more specifically dated to that exact moment in time with the genre than this. Coming from Japan as a manga/anime franchise, you've got Bosozoku/delinquent thug elements similar to Osu!! Karate Bu before it, as well as the transplanting of occult/horror and demon/ghost hunting Wuxia elements to modern day Japan ala The Peacock King, all while bringing the afterlife/Bangsian fantasy-centric elements of the genre into the central focus with vast chunks of the series set in the Spirit and Demon Worlds.

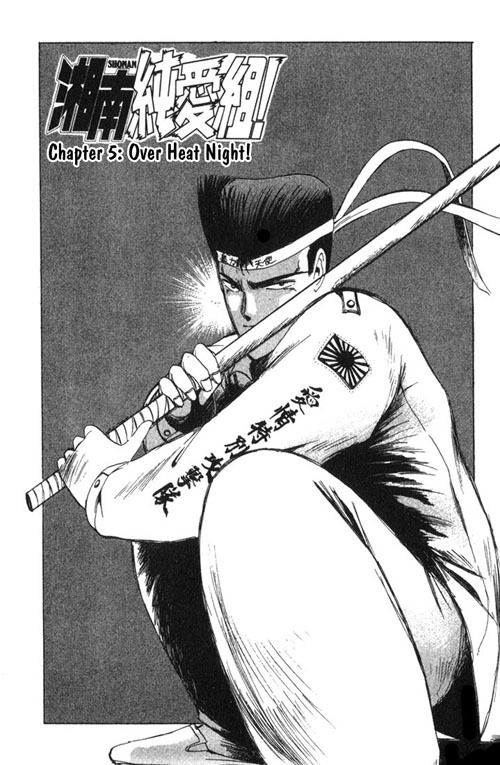

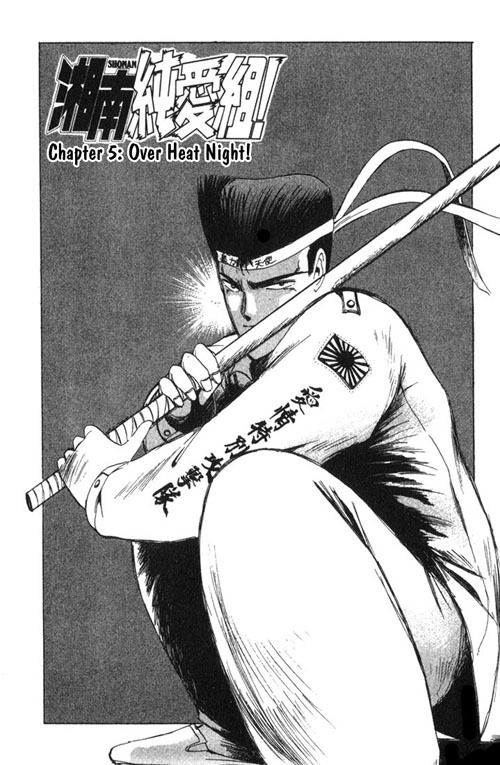

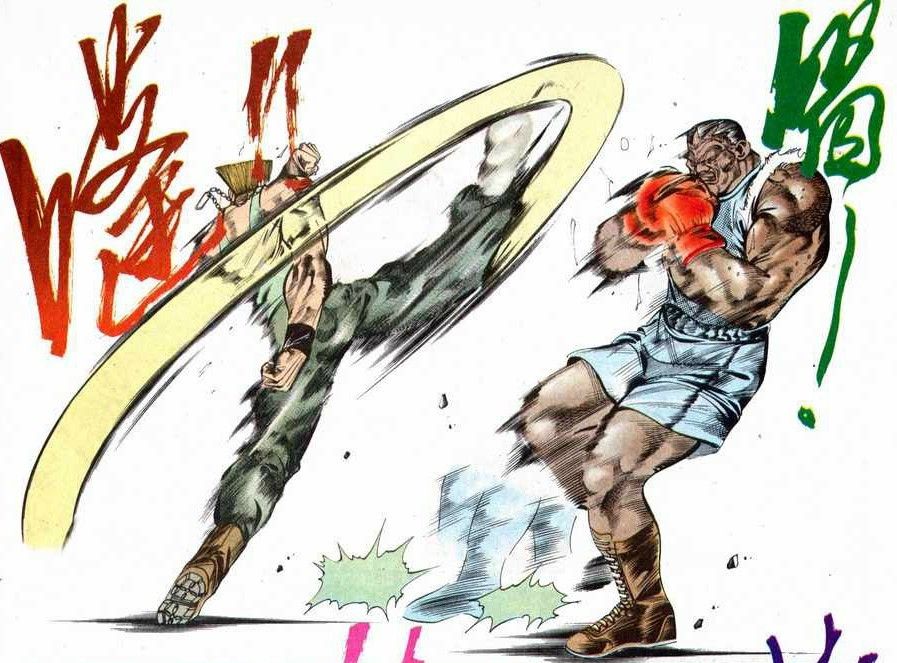

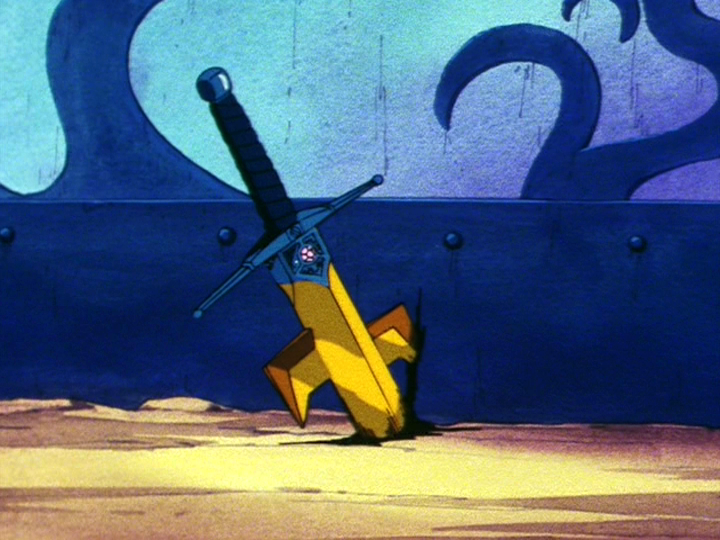

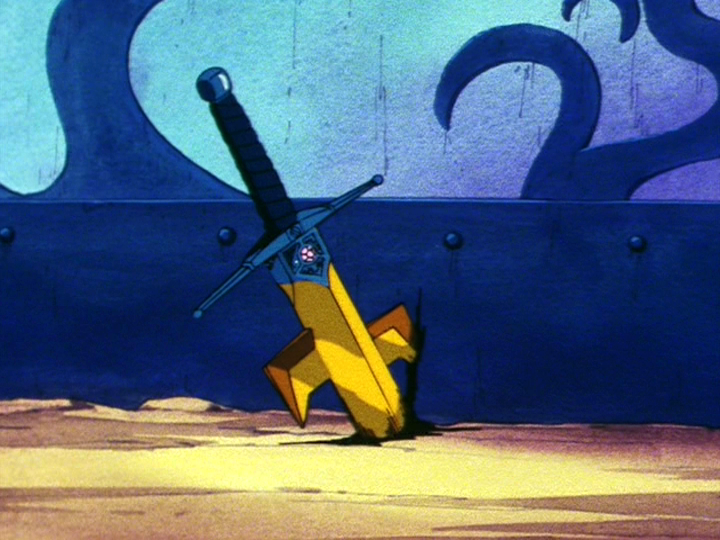

(Kuwabara's Rei Ken/Spirit Sword has a dual meaning: being both a Ki-powered sword wielded by a modern day Xia-like character, as well as a Wuxia-ified take on the wooden Bokuto swords often wielded by Bosozoku thugs, whose stereotypical Kamikaze tokko-fuku garb Kuwabara wears as his Xia warrior's dogi/robe of choice. In fact, the first time Kuwabara accidentally created a Spirit Sword from his Ki, it was through using the broken-off piece of an enchanted, mystically powered wooden Bokuto sword.)

Beyond even all that though, Yu Yu Hakusho is a rather intelligent and thoughtful deconstruction of the Youxia archetype by way of transplanting the extremely medieval and archaic nature of its warriors' ideology to a modern day early 1990s setting. Yusuke spends the vast majority of the series working out how to balance his natural, inherent desire to devote his life to growing and blossoming as a supernatural martial arts master with the vastly more liberal and nuanced morality and social responsibilities of modern living, and each of his major rivals and opponents act as generally three dimensional and achingly human examples of where he can go astray in walking the precarious tightrope he spends the series walking.

The incredible success of the post-HK New Wave genre-hybridization and modernizing formula for Wuxia had indeed left its mark on Japanese pop culture through numerous highly popular Seinen and Shonen manga and anime. This would only further continue across ever more mainstream Japanese properties well before the 90s would even reach its back half.

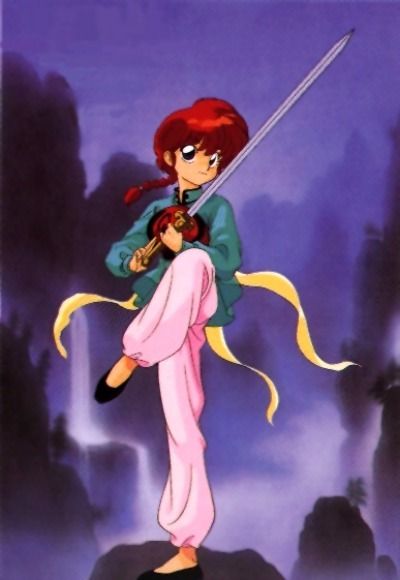

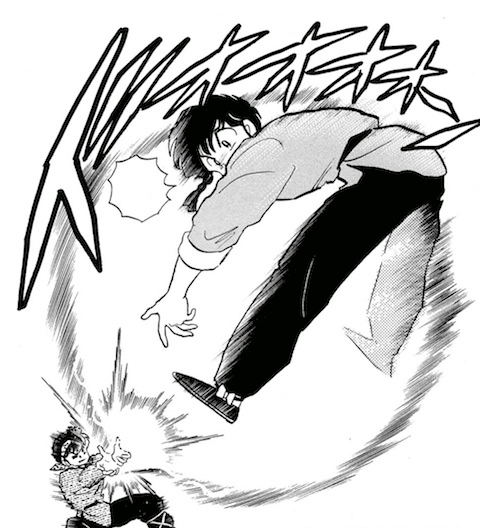

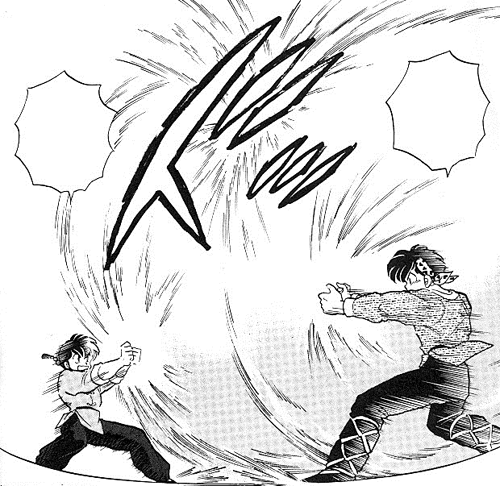

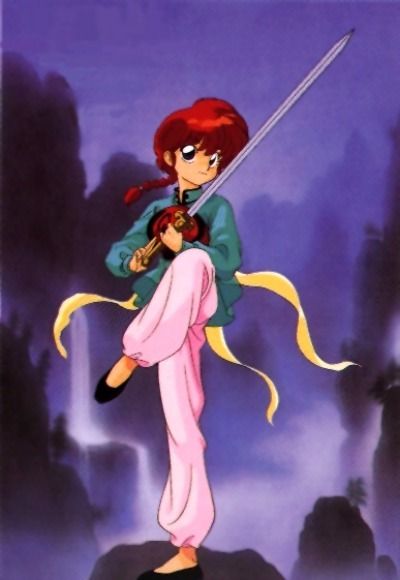

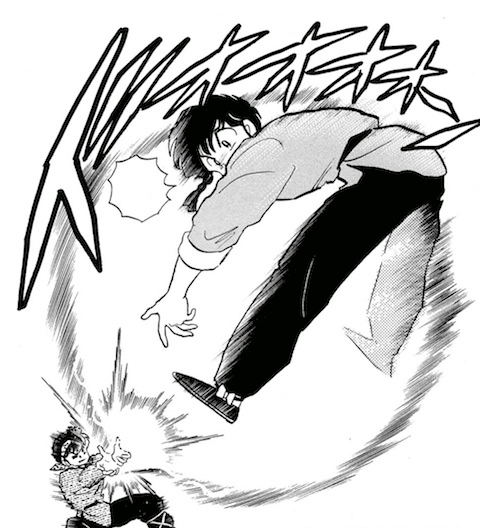

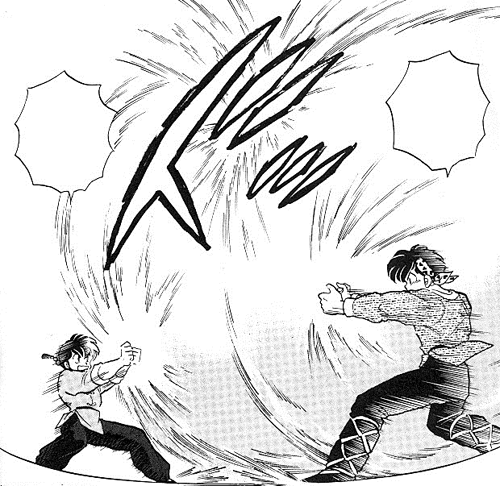

Rumiko Takahashi would dip into the craze a bit with her seminal and hugely influential gender bending martial arts/sex comedy Ranma ½, which sprinkled Wuxia elements of Chinese kung fu mysticism and martial arts rivalries throughout an otherwise farcical “harem” comedy set in modern late 80s/early 90s Tokyo.

[

[

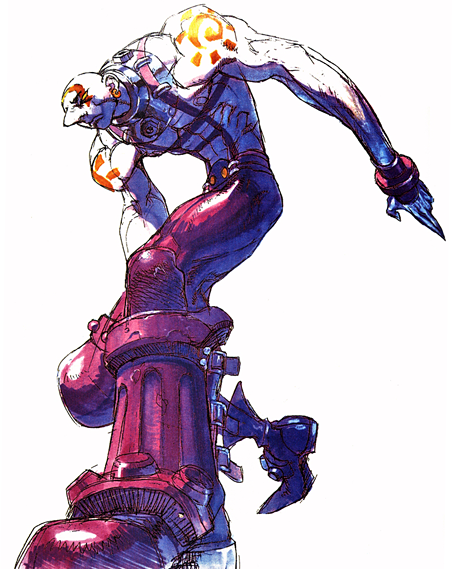

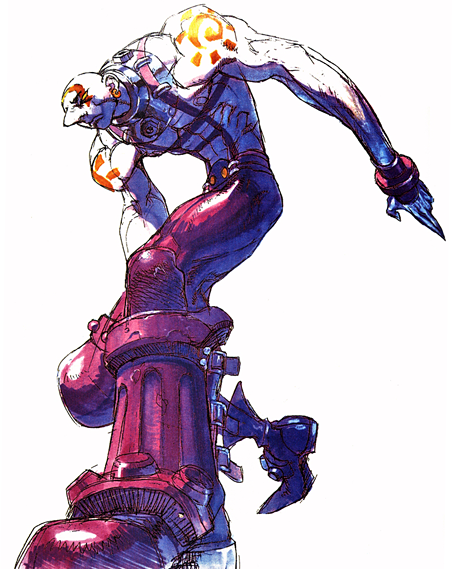

Another popular children's anime franchise to unexpectedly be influenced by the ever-increasing spread of blending Wuxia with other genres by the early 90s was, of all things, the Gundam franchise.

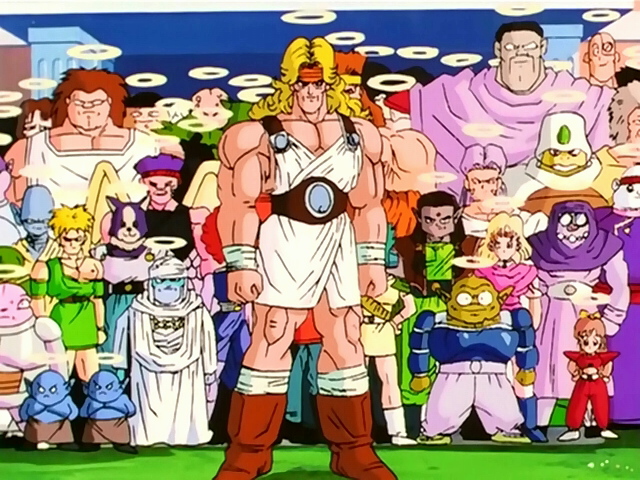

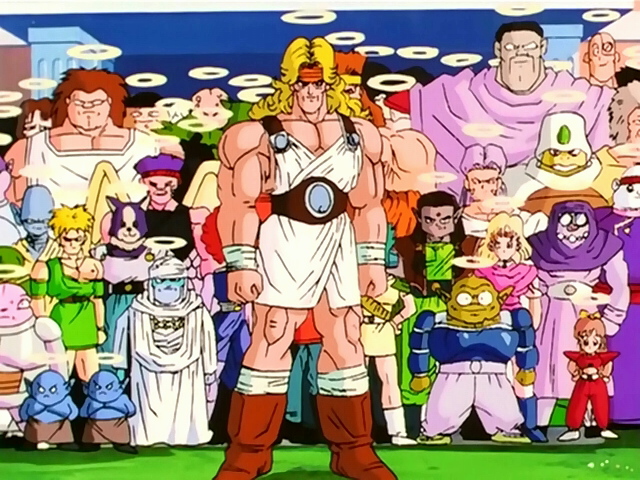

The... ahem... somewhat controversial series Mobile Fighter G Gundam built itself on the premise of essentially being a Wuxia Gundam series, owing to its creator Yasuhiro Imagawa's love of international films, particularly Hong Kong Wuxia and the films of Tsui Hark. Within the series, ruling power over the universe is decided every few years with a martial arts fighting tournament, each world nation being represented by a Gundam battle mech whose pilot (usually an expert martial artist themselves) controls the robot via their own fighting movements, making the Gundam mimic every punch, kick, and various supernatural martial arts Ki techniques that the pilot performs.

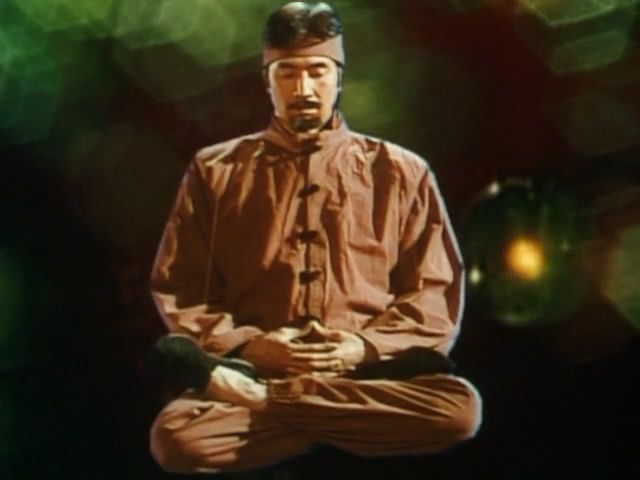

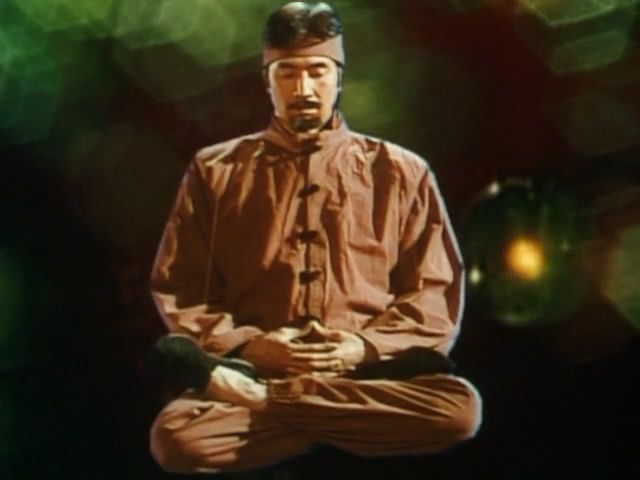

Apart from the obvious parallels, the character of Master Asia's Japanese name Toho Fuhai, is actually the Japanese translation of the previously mentioned Smiling Proud Wanderer character Dongfang Bubai, an intentionally direct homage.

By 1993, even that year's annual Super Sentai series would be Wuxia themed: Gosei Sentai Dairanger, which focused on the main team's growing Chinese kung fu/Ki proficiency and training as well as numerous references to creatures and deities of Chinese folklore with its mecha. The villains they faced, the Gorma Tribe, were an ancient martial arts clan who achieved such powerful mastery of their bodies and their Ki that they grew third eyes: this concept is taken directly from a piece of Taoist lore that pops up in Wuxia from time to time and will be further touched on later.

Even the power by which the Dairanger team transforms stems from their ability to harness and control their own Ki, their costumes designed after Chinese kung fu training clothing, and many of their weapons being based on Chinese medieval martial arts weapons common to Wuxia: their quarter staffs in particular suspiciously and likely intentionally resemble Sun Wukong's magical staff.

The continued virus-like spreading of post-HK New Wave Wuxia's influence (and the influence of the various works it had by the early 90s already influenced) hardly stopped at Japanese comics and TV shows though. It of course had a HUGE impact on video games, and is essentially responsible for creating one of the most defining game genre's of the early 90s.

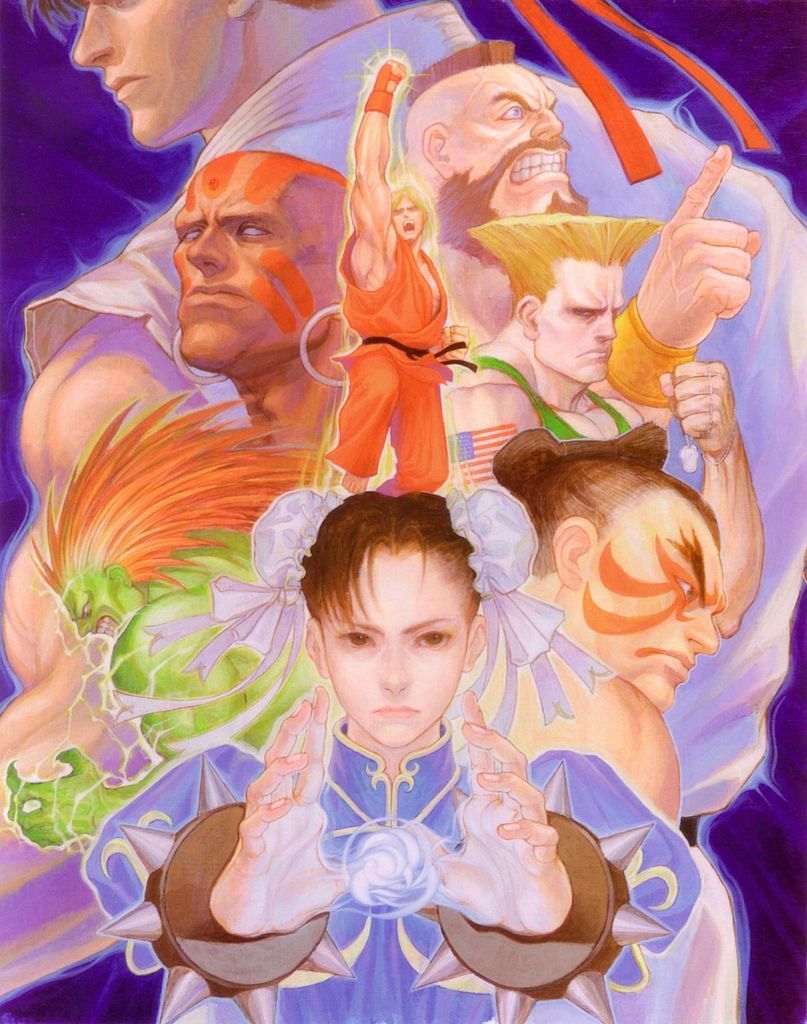

Once more, I believe this one needs little to no introduction.

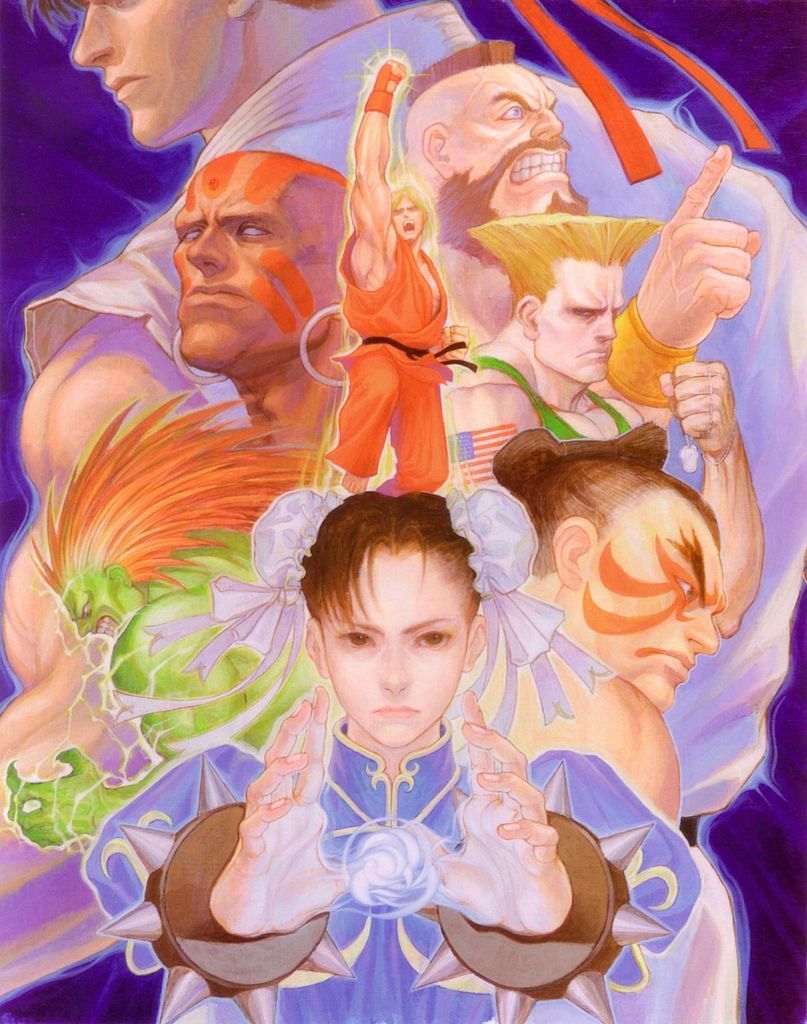

But for the benefit of those living under a fucking rock for the past 20/25 years now: debuting in arcades in 1991, Street Fighter II is one of the most important flagship franchises of legendary game development studio Capcom and an absolute icon and benchmark of arcade gaming, radically redefining the arcade landscape for what would essentially be its final decade of existence as a cultural entity. It codified and more or less created from wholecloth the vast lion's share of the fundamentals for the modern 2D fighting game as we know it.

The characters and lore behind the Street Fighter series is of course absolutely the byproduct of an Asian popular culture that had for more than a decade before been inundated throughout every pore with modernized and hybridized takes on classic martial arts fantasy fiction.

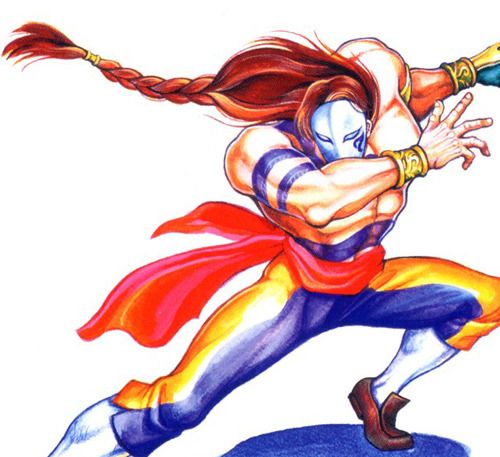

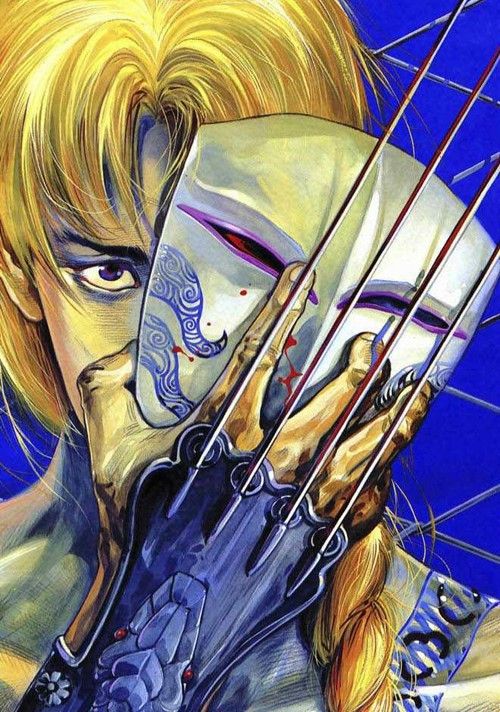

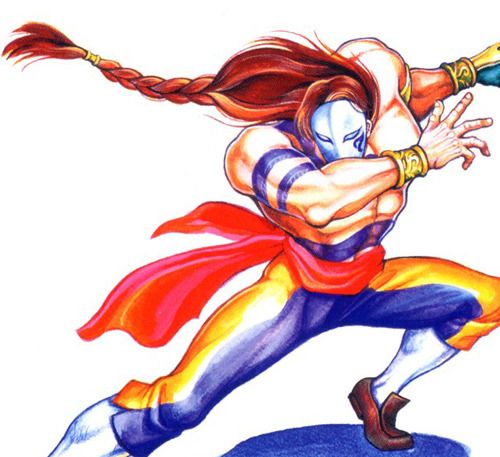

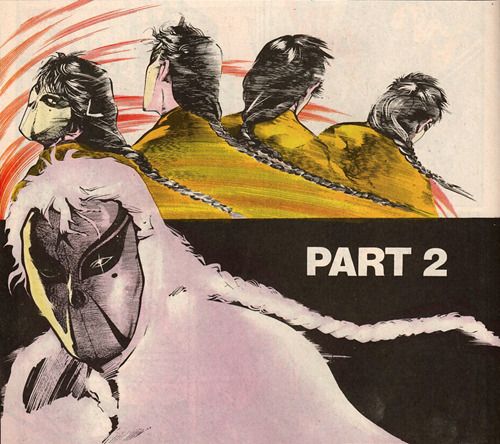

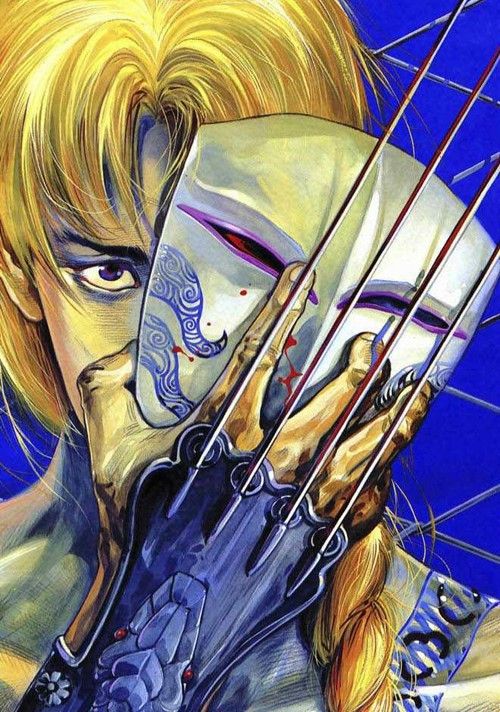

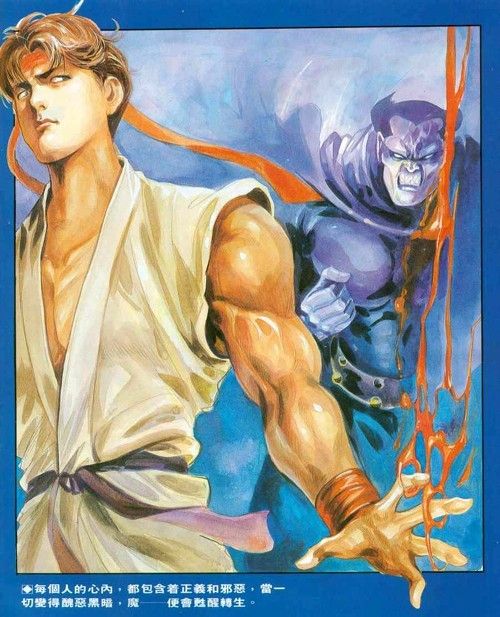

(The look and aesthetics of many pieces of 70s and 80s Wuxia manhua, manga, and movies, genre blended and otherwise, fueled the look and feel of Street Fighter II's stew of fantasy martial arts mixed with modern sensibilities, as was the well established trend of the time. Here you can clearly see that Vega/Balrog's masked/braided ponytail look was largely taken from the armless warrior Ghost Servant from Chinese Hero. In Chinese Hero, Ghost Servant wears the mask to hide his gruesomely disfigured face, while Vega/Balrog wears his to shield and protect his delicately beautiful and handsome features, which may have been an intentional reference/subversion.)

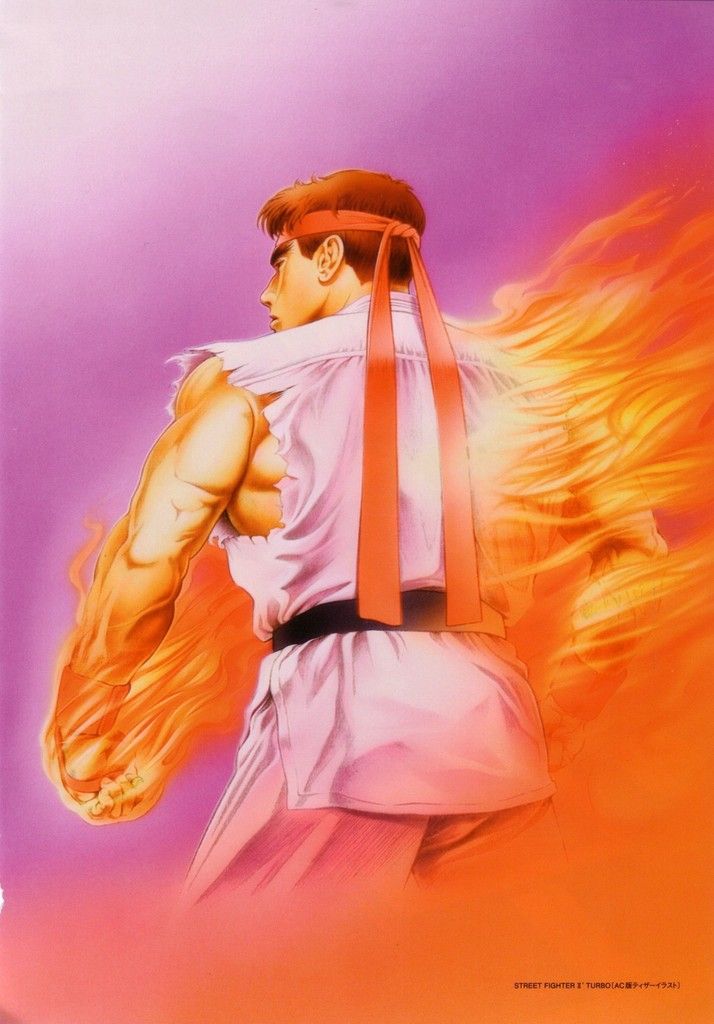

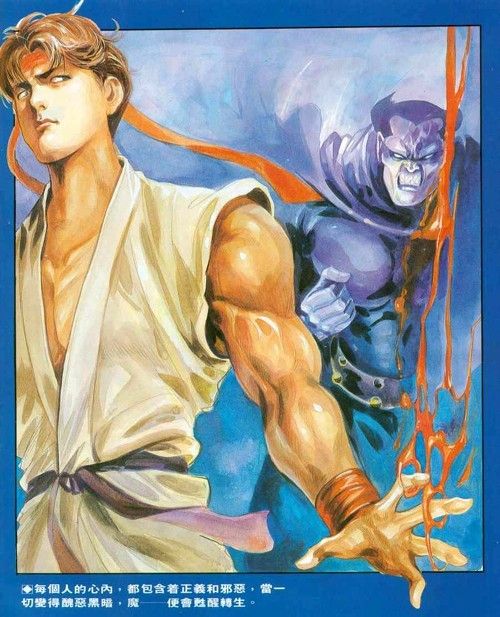

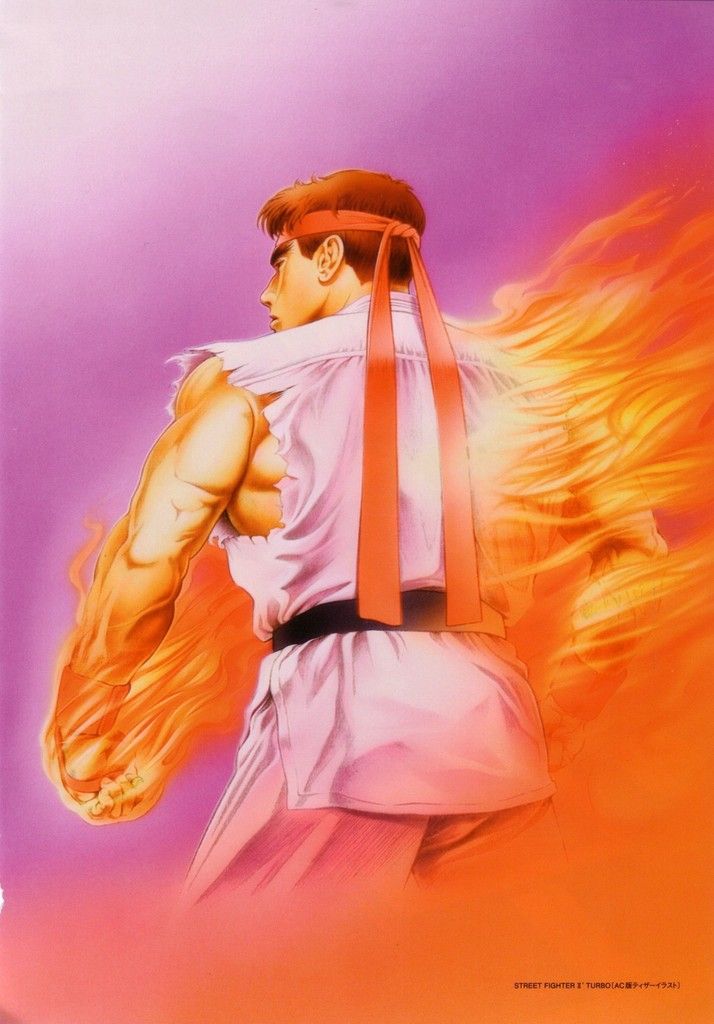

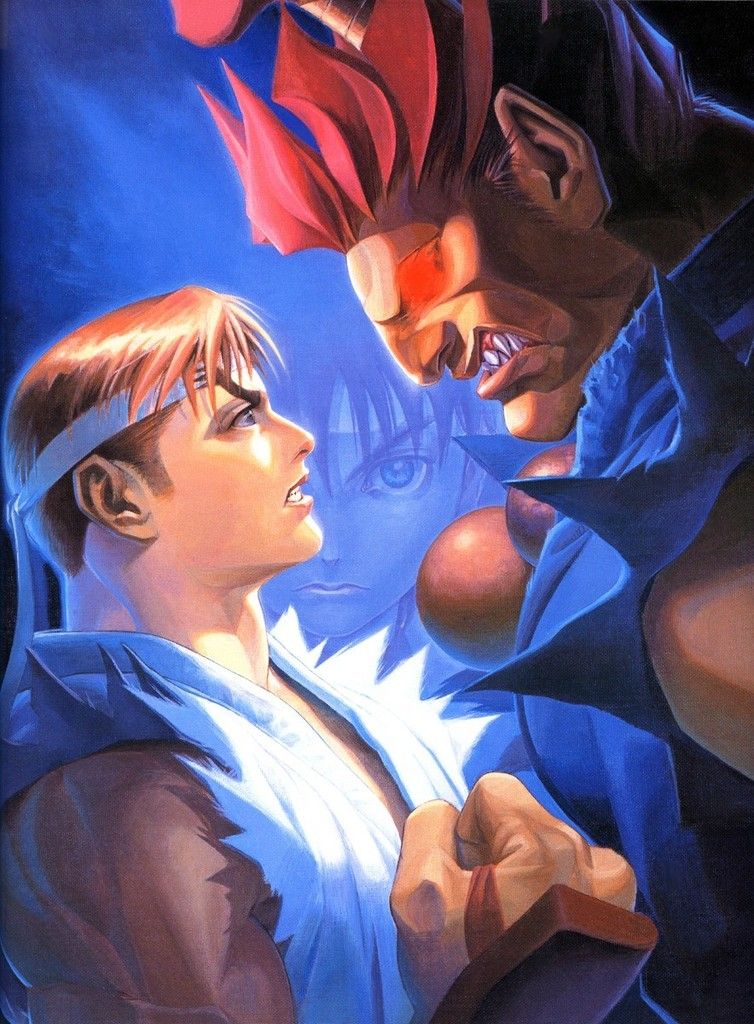

The main character Ryu is essentially a modern day classical Youxia (mixed heavily with numerous elements of actual real life Japanese Karate masters, namely Mas Oyama), a pure warrior constantly and restlessly wandering the globe in search of new challenges to push his martial arts skills to and beyond their absolute limits. Ryu embodies and lives for nothing but the purity of the fight while striving to maintain the integrity of his honor as a martial arts master: you cannot possibly distill the crux of the Youxia archetype down to its barest essence more than this.

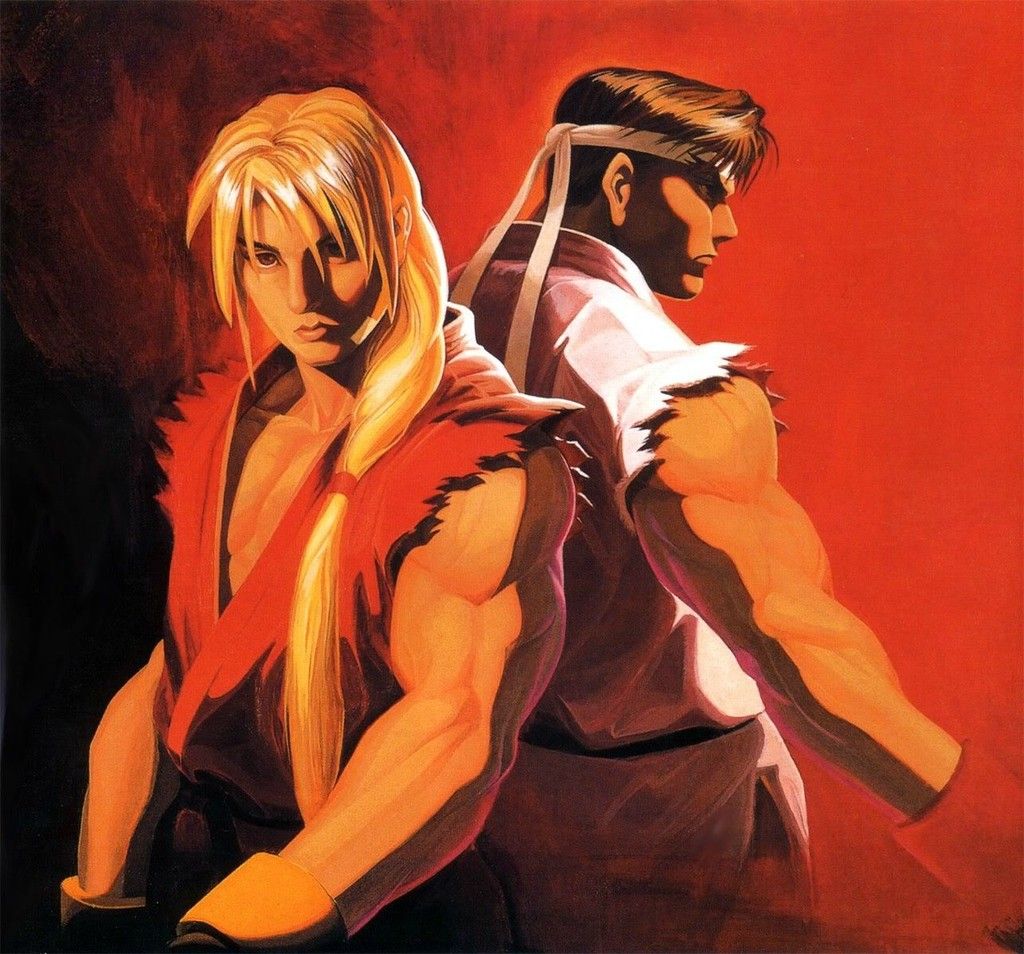

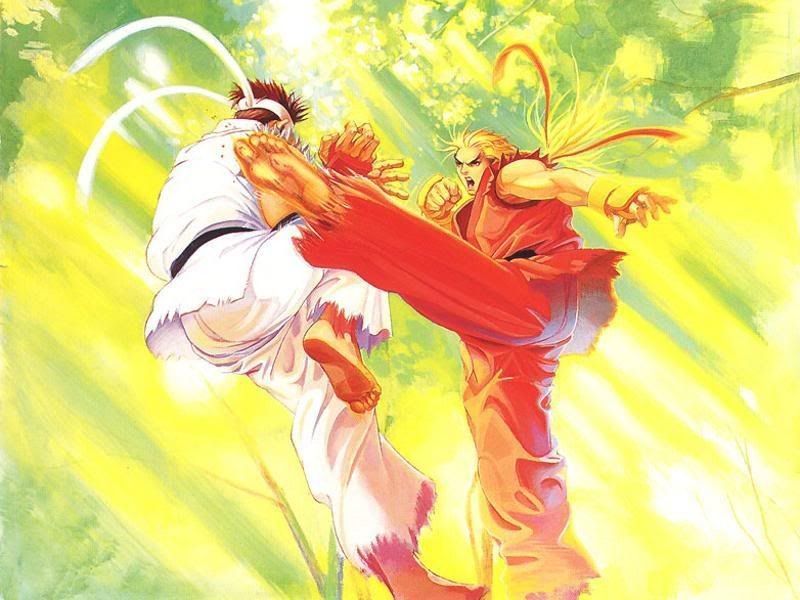

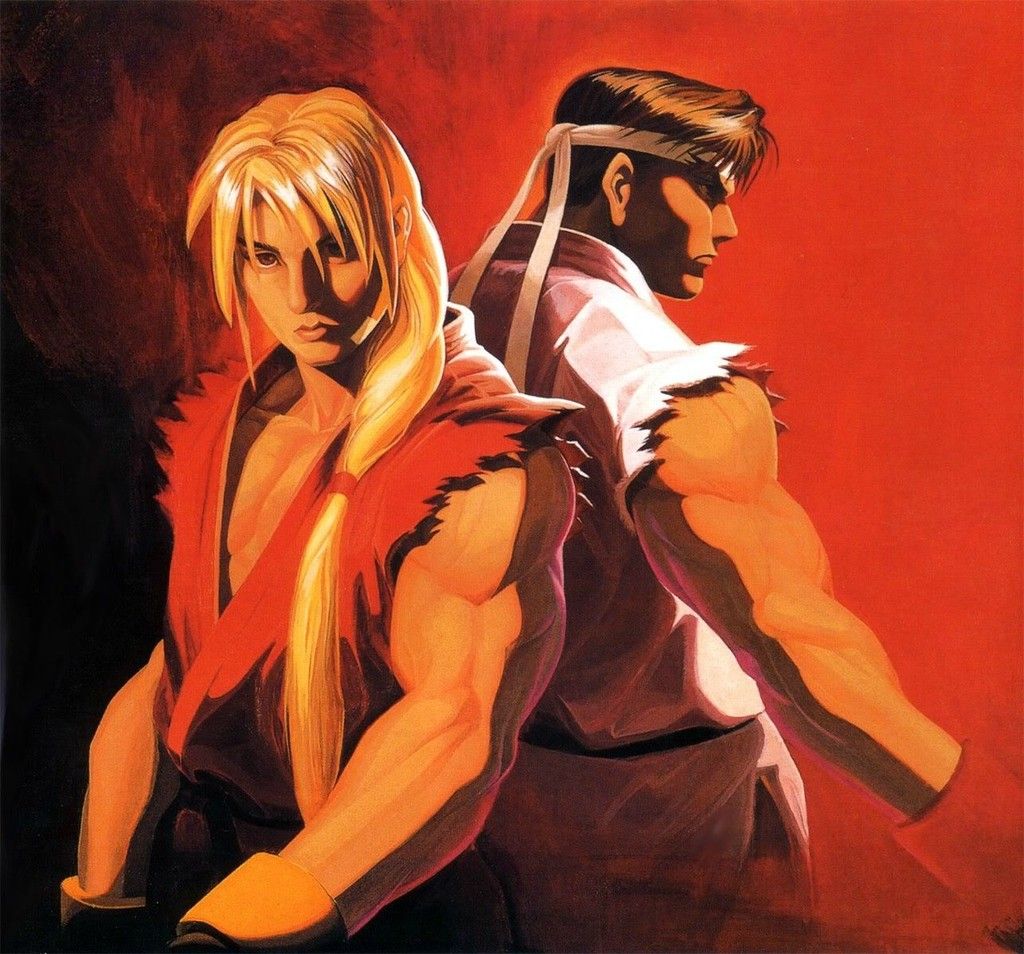

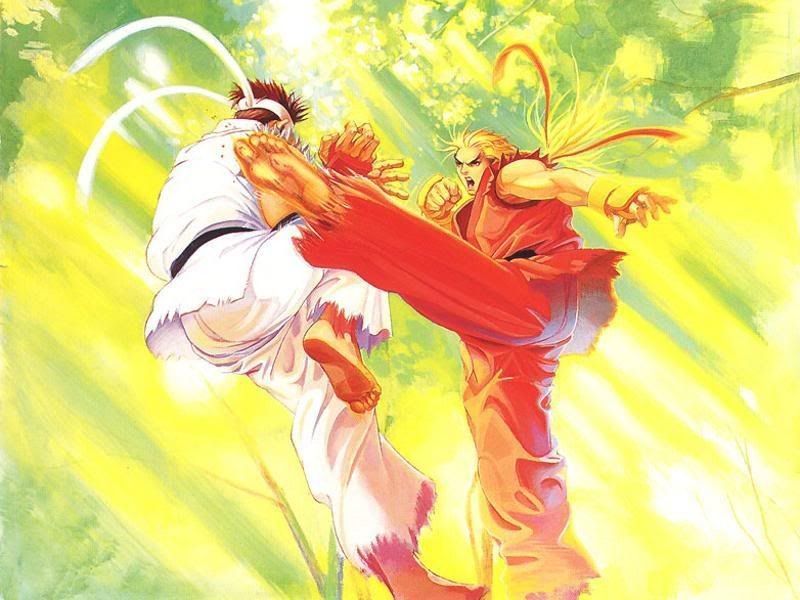

Ryu of course, like any good Wuxia protagonist, is also just as much defined by his rivals as he is his own skills and code of fighters' ethics. His best friend Ken Masters is every bit his American counterpart: brash, energetic, humorous, high spirited, and a bit arrogant, Ken is very much the more down to earth Yin to Ryu's ever stoic Yang, and the careful balance between the pair's deep friendship as lifelong training partners and students under the same master as well as hot blooded rivals in their mastery of their skills is very much at the heart and soul of the series' mythos.

With an international and multi-ethnic cast of warriors each representing a different culture as well as a different fighting style, Street Fighter has over the course of its dense history covered just about close to every possible martial arts character archetype in existence and each of them make up what is essentially within the series' universe a modern day 1980s and 1990s Wulin community: supernaturally powerful martial arts masters who train and exist quietly and on the far fringes of society, making their presence known primarily to test their skills against one another at large gatherings of great masters at major martial arts tournaments, such as those hosted in the series by Sagat and later the criminal empire Shadaloo.

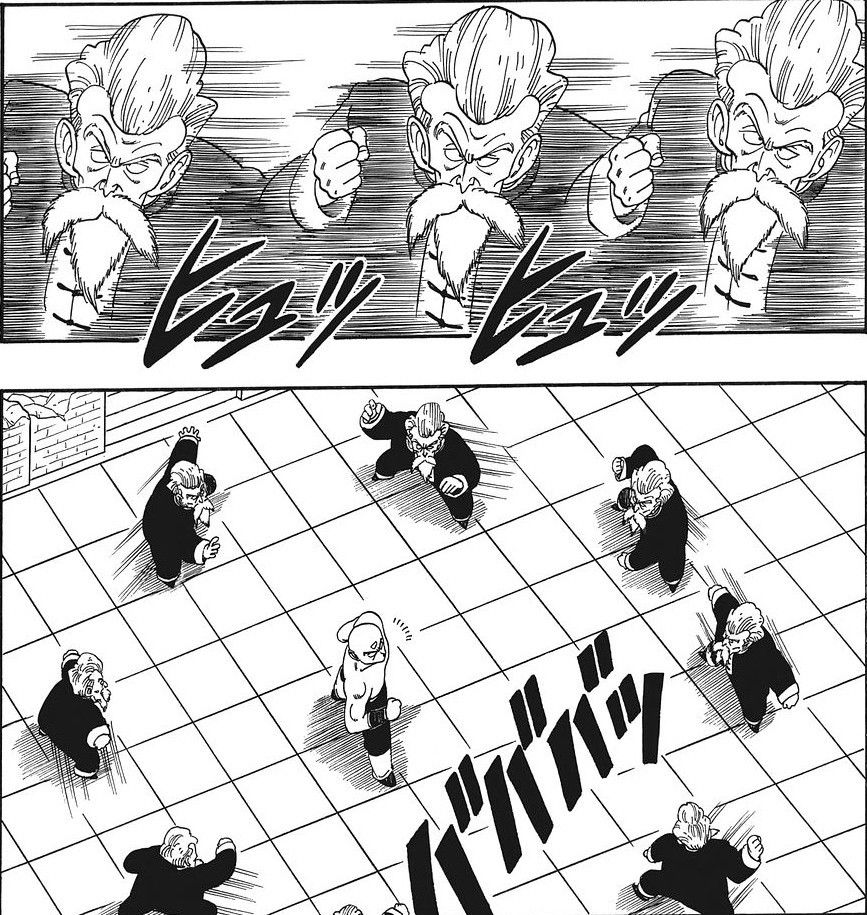

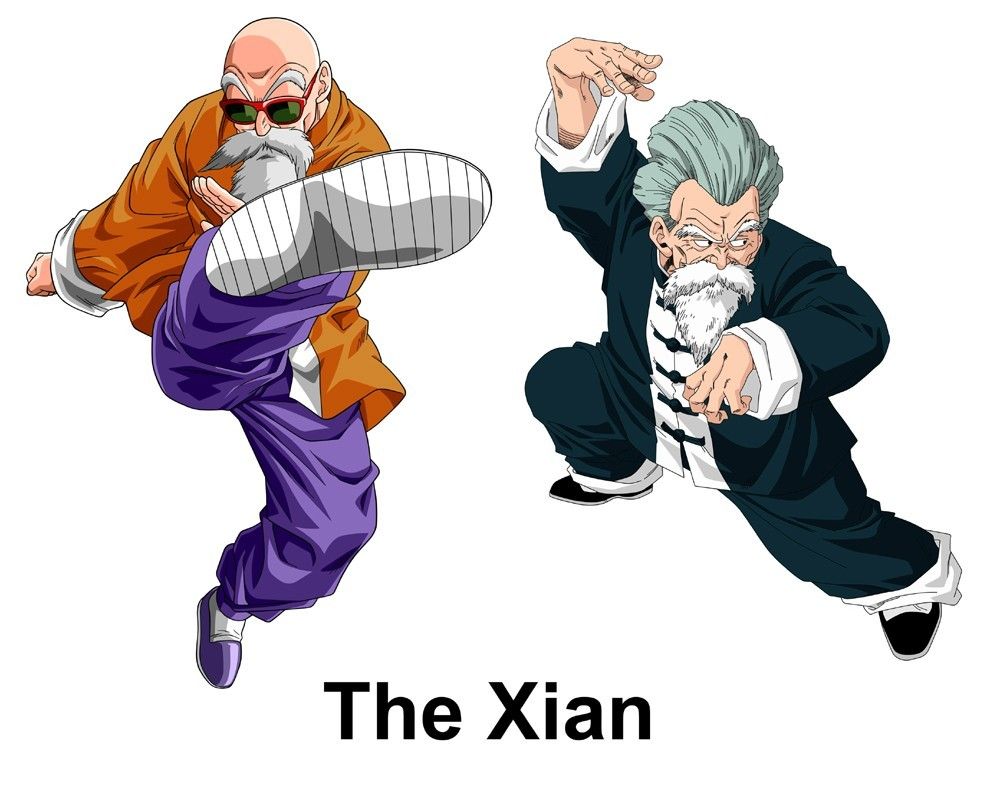

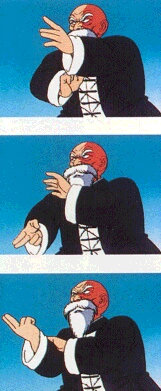

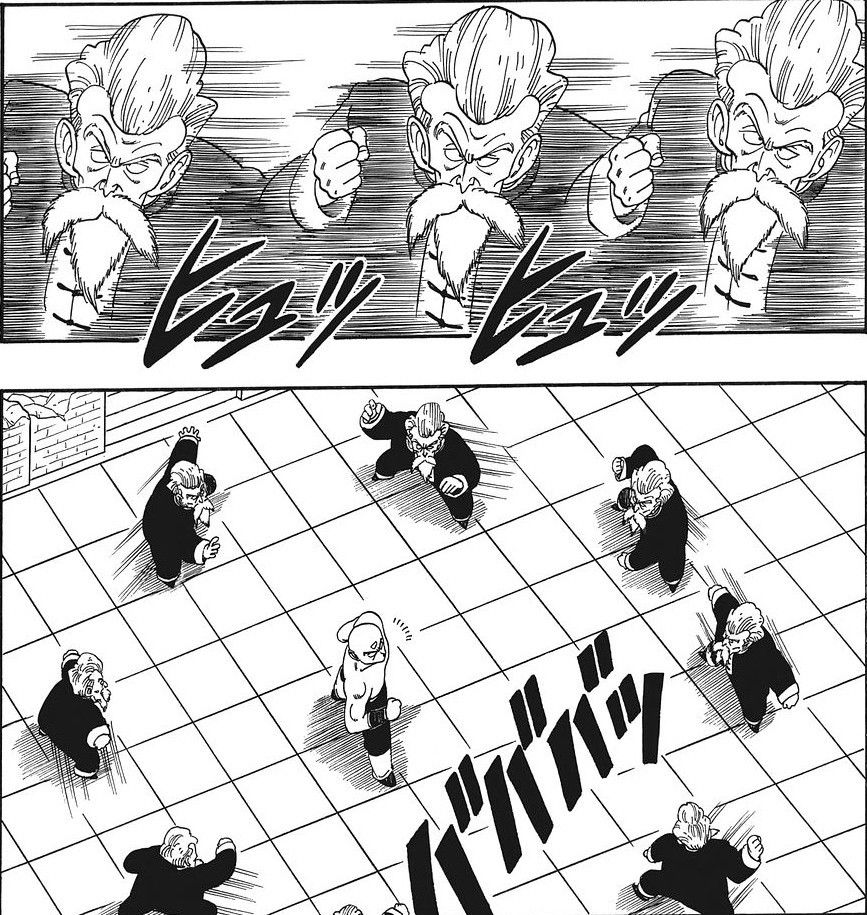

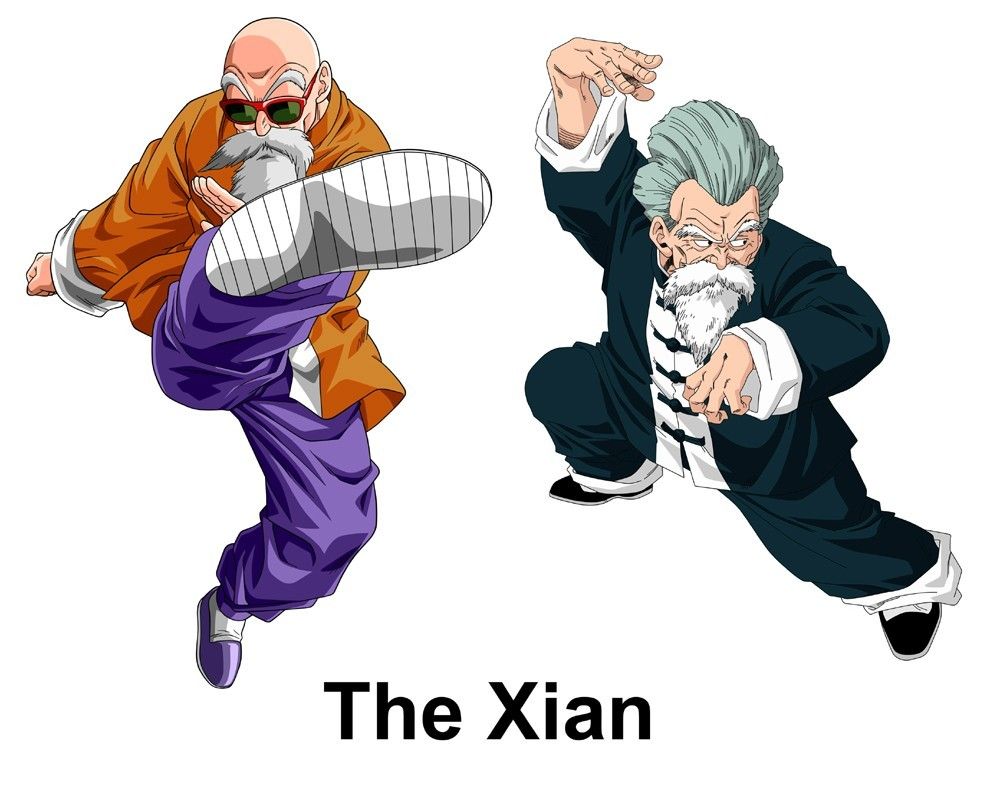

The character Gen for instance, a semi-retired and terminally ill kung fu hitman, is a tribute to virtually every Xian stereotype there is, as well as embodying numerous aspects of countless martial arts assassin characters made especially popular during Shaw Bros. and Golden Harvest's heyday.

Then of course there's the superpowerful psychic martial arts master and drug lord/dictator Vega (or M. Bison if you'd prefer) who takes as much from Japanese folklore and pop culture (namely Hiroshi Aramata's classic apocalyptic occult/onmyodo historical horror epic Teito Monogatari and its iconic villain Yasunori Kato) as he does every possible stripe of Chinese Wuxia warlord characters. Vega/Bison spends much of the series fascinated with Ryu's potential as a fighter and finding ways of exploiting it for his own goals of conquest.

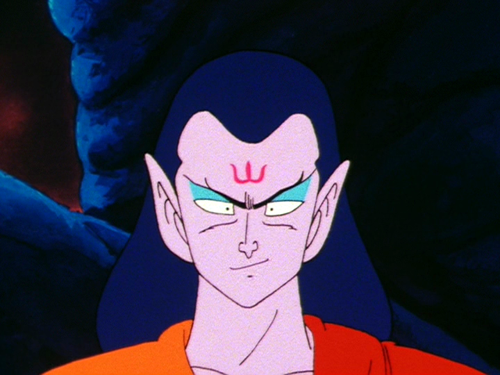

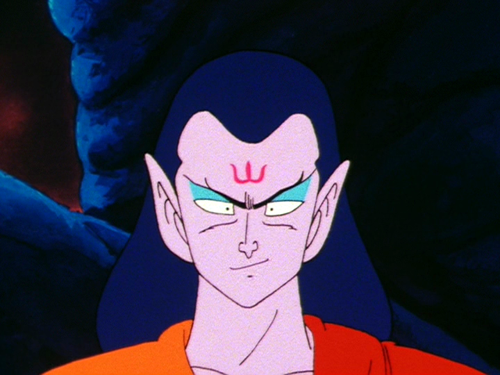

(On the left: Teito Monogatari's Yasunori Kato. On the right: Street Fighter's Vega/M. Bison)

Also on hand is Chun Li, who lends much more of an overtly Chinese flavor to the proceedings (albeit a fairly modernized one, fittingly enough) as well as a more classical “revenge for a slain loved one” storyline that is so indispensable to the martial arts/Wuxia genre.

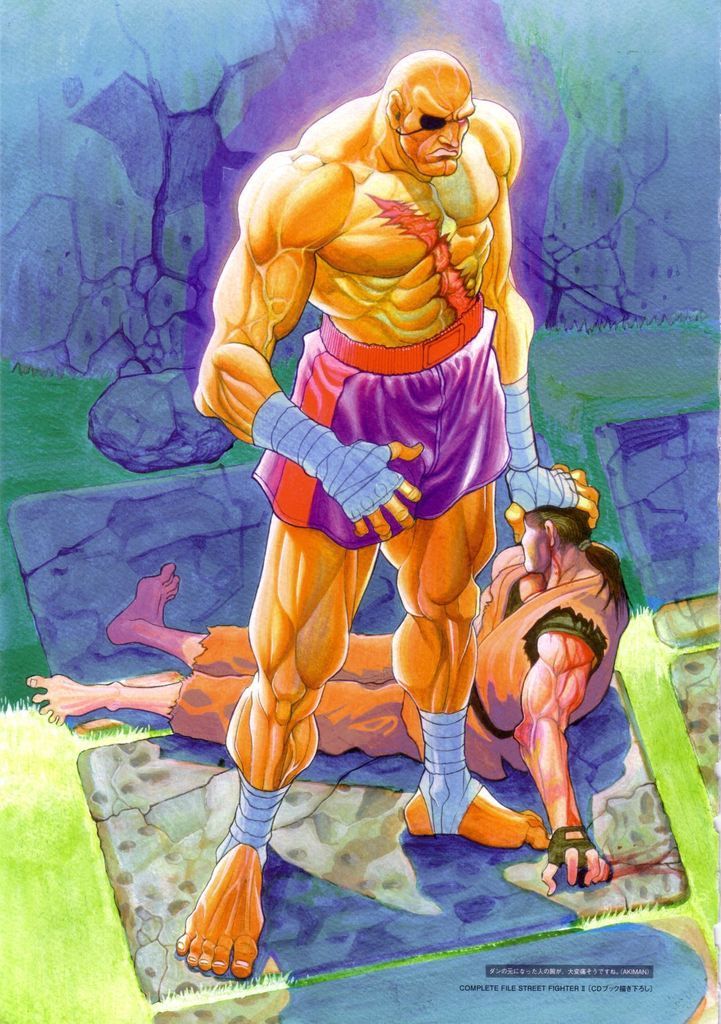

Also notable are the characters Sagat and and somewhat later on Gouki aka Akuma, a pair of dark analogues to Ryu (similar in many ways to the relationship between Yusuke and Toguro/Sensui in Yu Yu Hakusho) whose obsession with fighting and pushing their skills to their utmost breaking point takes on deeply twisted and corrupt perversions of the Xia's warrior code: though in Sagat's case, not without the possibility for redemption.

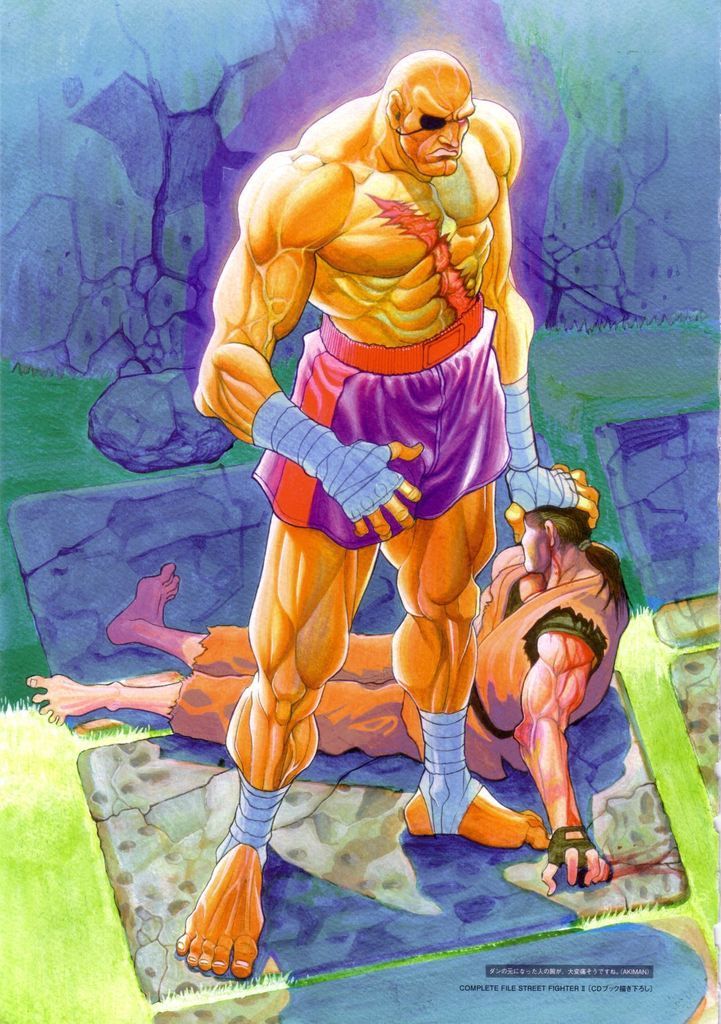

Sagat is driven into a mad fit of obsession over his (literally and figuratively) scarring loss to Ryu, which he perceives as unfair, and sells his soul and his ethics as a warrior to the service of Vega/Bison for the chance to even the score and avenge his crushing defeat (and always with deep pangs of regret for the trade off).

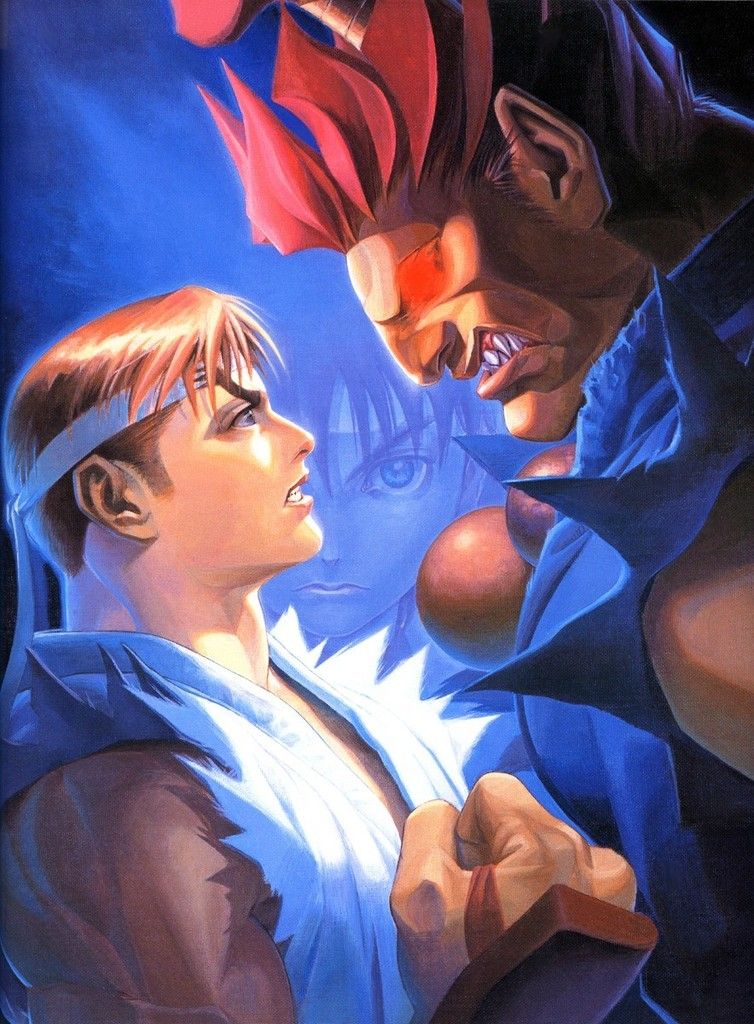

Gouki/Akuma meanwhile is the worst possible tragic outcome of a Youxia gone bad: the brother of Ryu and Ken's master Gouken lead astray into mastering corrupt techniques and martial arts teachings for the sake of fueling his own ego and lust for undisputed dominance in the martial arts world, Akuma like Bison sees in Ryu his incredible potential as a fighter and wishes for Ryu to go down the same dark path of mastery as he did under the belief that it is the only true way for Ryu to fully meet his potential and give him (Akuma) the only true challenge left to his skills as a demonic, twisted Youxia fighter.

Part of what's long made Akuma so fascinating as a character is the fine line he generally walks between a semblance of warriors' ethics and outright martial arts villainy. Within the context of the modern day Wulin-esque martial arts world of Street Fighter, Akuma is absolutely unquestionably evil as his yearning to explore and push past his own limits is driven more by vanity and a ruthless need to dominate his challenges (as shown by his casual attitude towards killing and crippling his defeated foes) than by a more compassionate road of using his fights to help teach and train his defeated opponents as much as they teach and train himself.

However, even with all that said, Akuma still abides by SOME semblance of Xia ethics, and will not use his skills and power to victimize completely innocent civilians who do not strive to be fighters at all (unlike Bison, whose corrupting power is a danger to all). Akuma's major flaw that makes him “evil” within the context of a Wuxia story is his total lack of compassion for fighters whose skill is beneath his own. In some stories he could be finagled to be seen as more of an anti-hero: in a martial arts narrative however, his attitude posits him unquestionably on the negative end of the spectrum, a fighter who has clearly lost his way and whose honor has been tainted by his own ego.

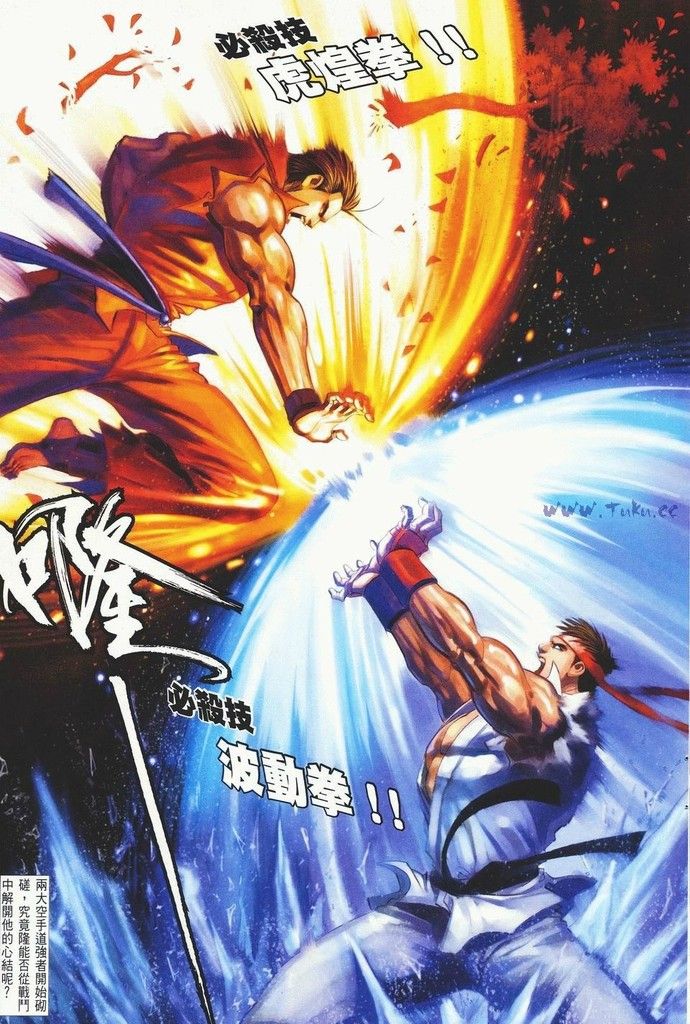

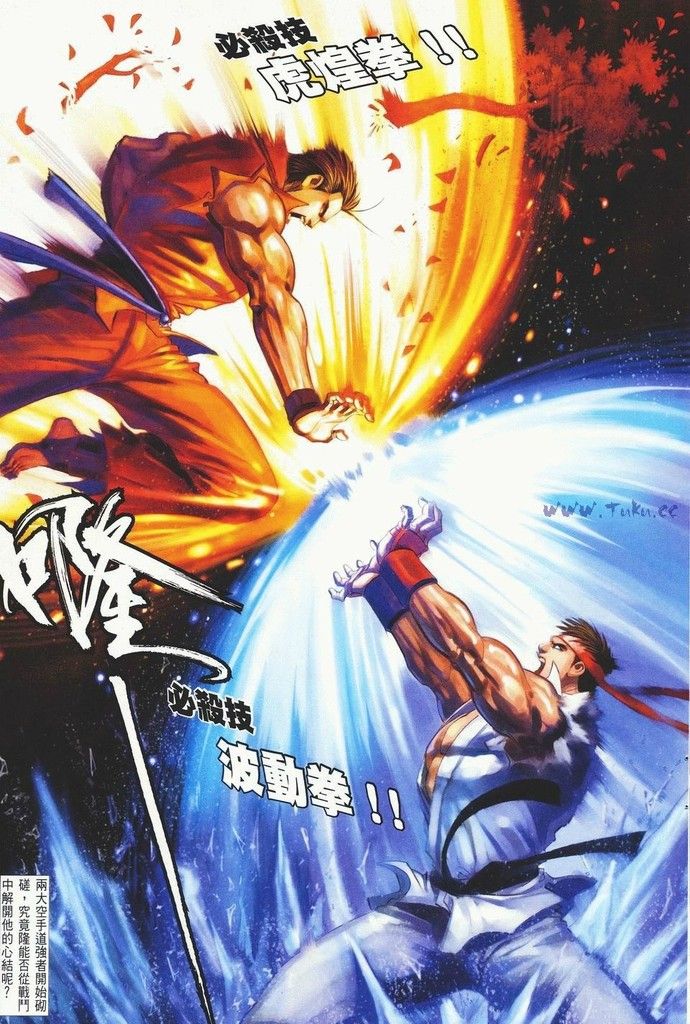

Much of the lore of Street Fighter is centered around the concept of Hadou, which is essentially the series' version of Kikou/Ki mastery, and its dark and light incarnations: essentially based off the real life Taoist concept of positive and negative energies in Ki (thus once again, Yin and Yang) with Satsui no Hadou (Surge of Murderous Intent aka Dark Hadou) being a tempting and corrupting influence on powerful fighters - particularly Ryu who spends much of the series struggling against the temptation of giving into Satsui no Hadou in the heat of combat - tapping deep into the energies of Hadou in order to use them to kill or otherwise horribly maim and cripple their opponent beyond the pale... once again tapping into the Wuxia theme of “excessive force is inherently evil and corrupting”.

Also as with much of Wuxia during this time (late 80s/early 90s) across other media, Street Fighter would also add many elements of straight up science fiction into its martial arts storylines, first with Bison's futuristic crime syndicate Shadaloo, then his plans centering on the creation of his “psycho drive” (a massive doomsday device which can vastly increase his psychic powers and supernatural fighting abilities to godlike levels) and various cloned “dolls” (mindless, obedient female servants created in a lab and culled from his own DNA), and even further later on numerous other warriors who are as much government science experiments gone wrong as they are fighters' of Street Fighter's own little Wulin community (characters such as Twelve, Necro, and Seth).

With its focus on martial arts rivalries and warring interpretations of ancient mystical martial arts teachings about powerful Ki mastery and battles raged against an oppressive dictatorial force by a loosely connected sect of powerful and far fringe Wulin martial arts masters, Street Fighter is indisputably a Wuxia tale brought once more to the modern world, as we've well established to be the running theme of the genre throughout the 80s and early 90s. And as with most Wuxia properties that took that track during that time, it paved the way to incredible success and immense, iconic popularity that endures even to this very day.

During its original heyday however, Street Fighter of course would spawn COUNTLESS imitators of its own within the video game world, thus kickstarting the 90s golden era of arcade fighting games. The vast overwhelming majority of these games likewise took their cues as much from various Chinese and Japanese martial arts and Wuxia fiction media, from movies to manhua, manga, anime, etc. as they did Street Fighter itself.

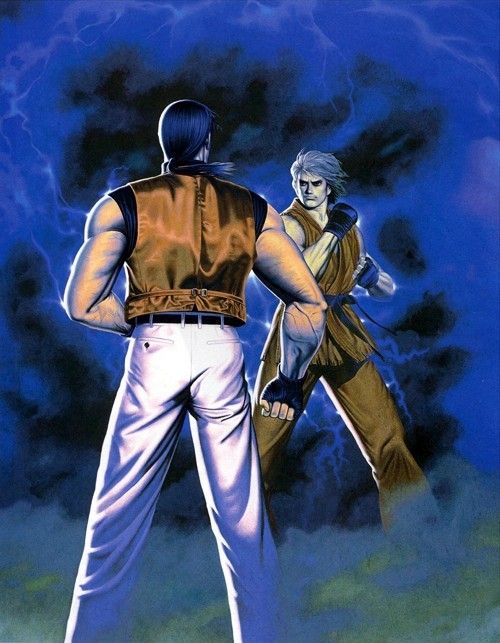

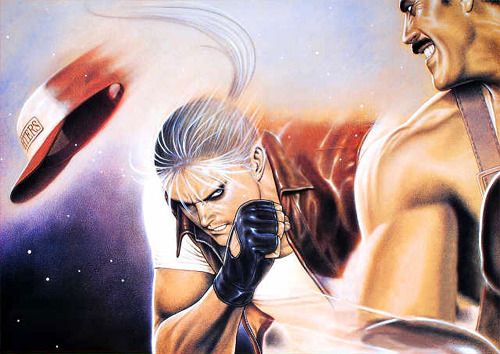

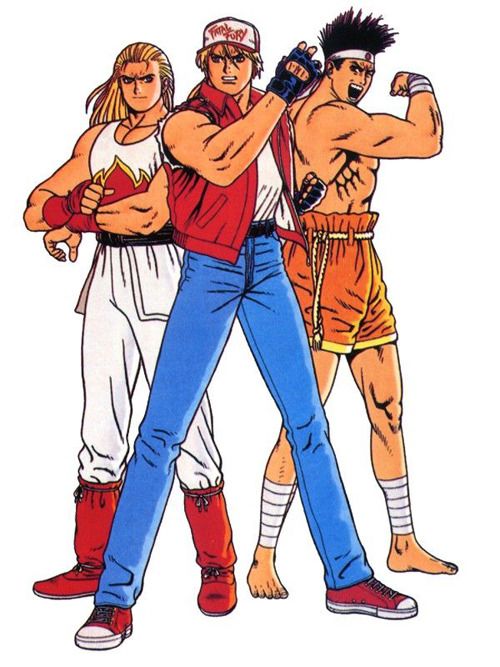

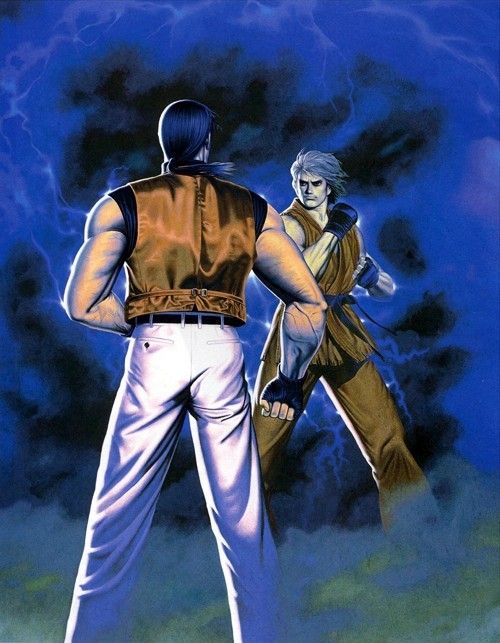

Without question the most successful of all of Street Fighter's fighting game/modern Wuxia progeny was SNK's King of Fighters universe.

Beginning with the two fighting game franchises Fatal Fury and Art of Fighting, those two series would eventually cross over along with numerous other SNK video game properties to create the King of Fighters fighting game franchise.

As with Street Fighter and the rest of Wuxia media during these years, the whole SNK universe of fighting games is a modernized take on numerous Wuxia storytelling tropes and character types retrofitted into a modern setting and often with futuristic elements mixed in for seasoning.

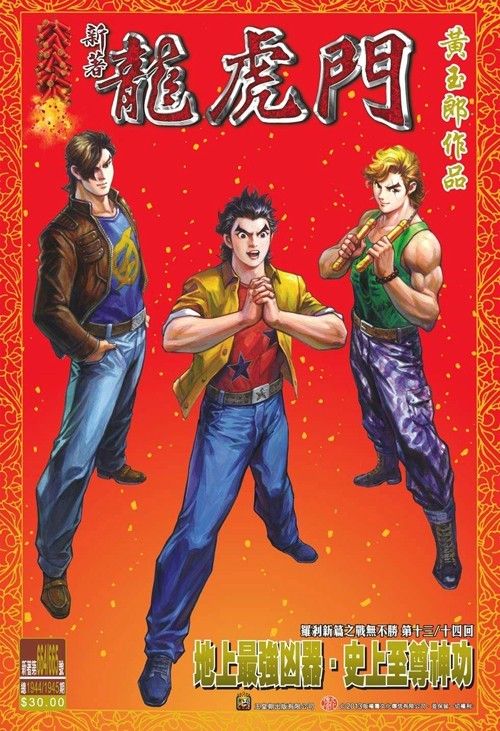

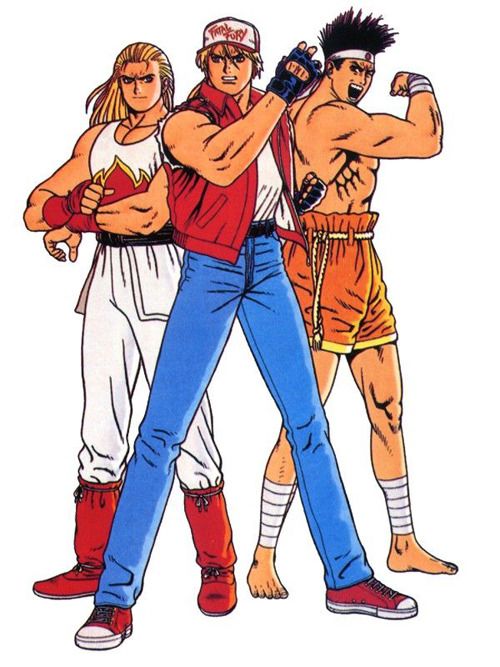

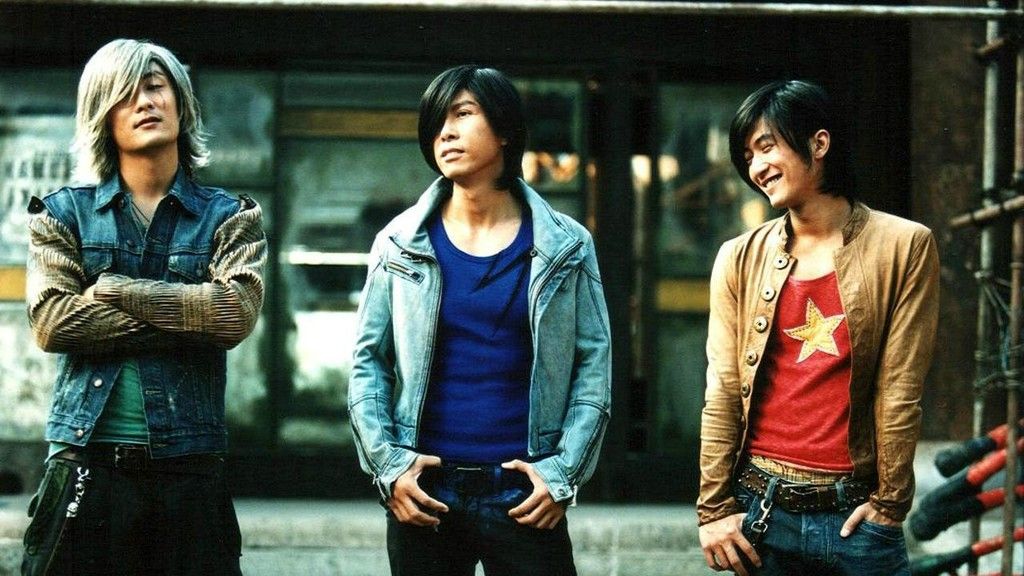

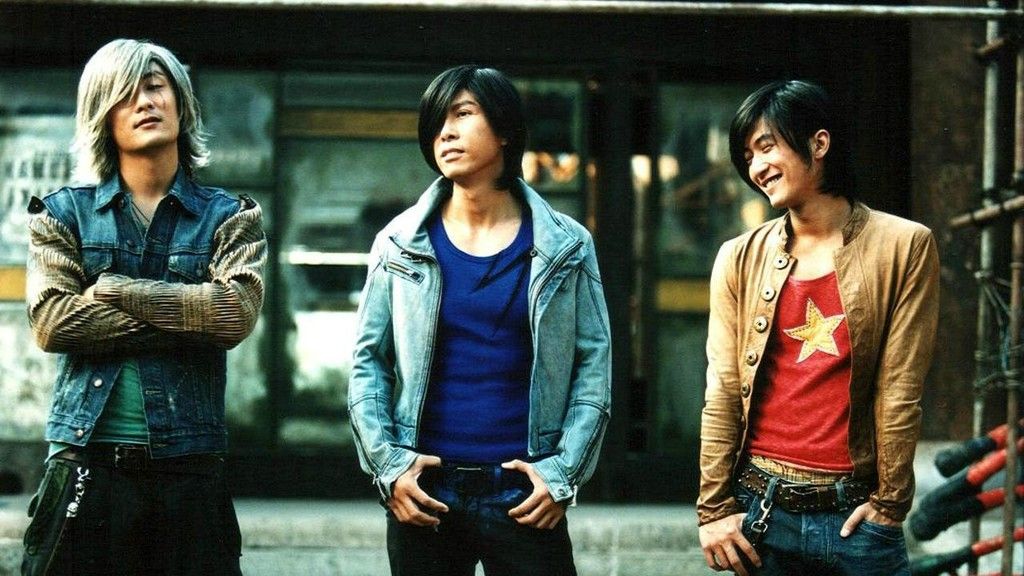

The main storyline for Fatal Fury, Art of Fighting, and King of Fighters as a whole centers around the fictional American city of South Town and the King of Fighters martial arts tournament that is annually held there by corrupt police commissioner and syndicate head Geese Howard, as well as the utterly massive international cast of superpowerful Wulin-like fighters that it attracts from around the globe, particularly the American brothers Terry and Andy Bogard and their close Japanese friend Joe Higashi: a very, VERY similar dynamic in fact to the Chinese brothers/half Russian best friend trio from Little Rascals/Oriental Heroes, and the gritty, hardboiled, crime ridden Chinese slums they inhabited not a million miles removed itself from the mean streets of South Town.

(Central characters Terry Bogard and Wang Xiao Hu even both share a similar “star” motif on most of their street clothing.)

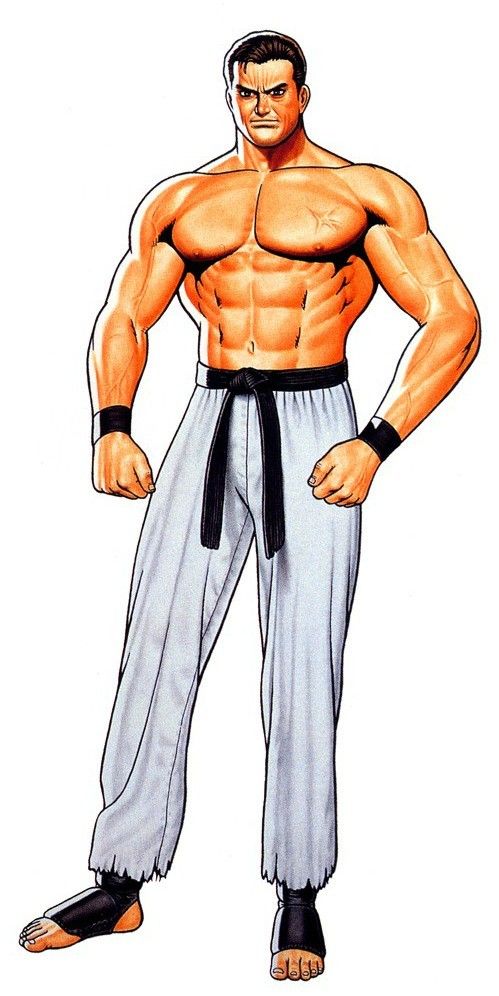

Characters like Art of Fighting's father/son duo Takuma and Ryo Sakazaki are as much staple martial arts/grindhouse/Wuxia character types as they are “heavily inspired homages” (to put it charitably) of Street Fighter's Ryu and other Ansatsuken (Street Fighter's own assassin fighting style practiced by Ryu, Ken, Akuma, et al) characters.

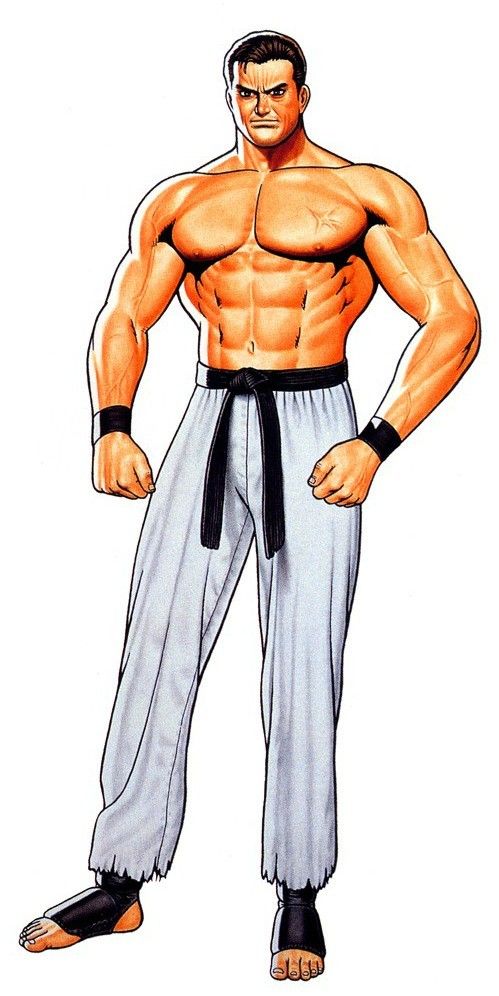

(You may possibly notice some mild similarities.)

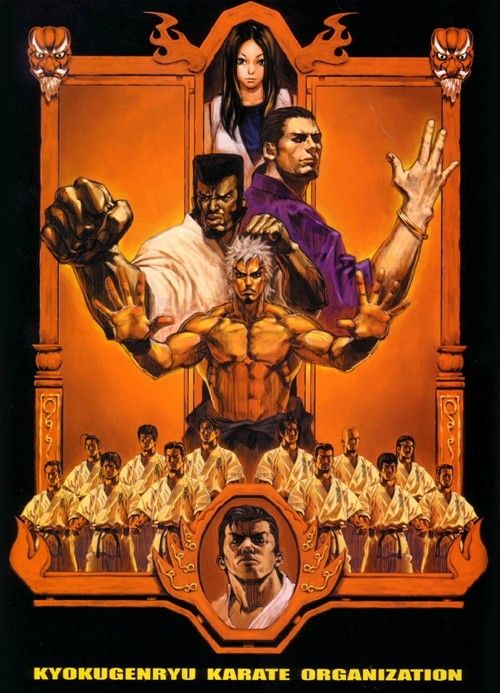

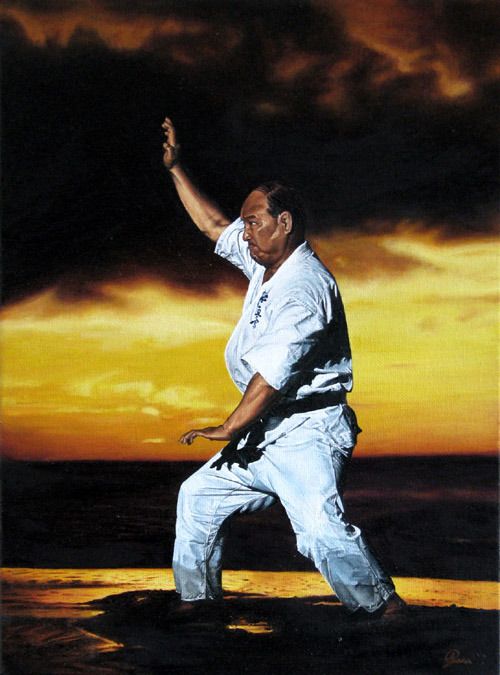

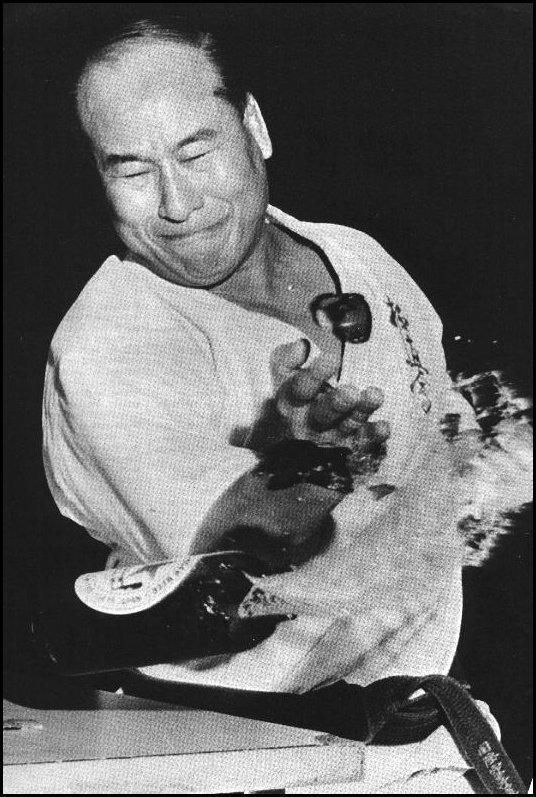

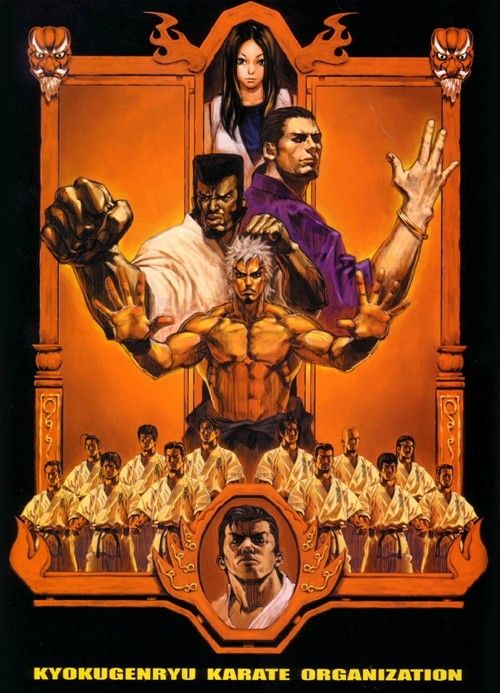

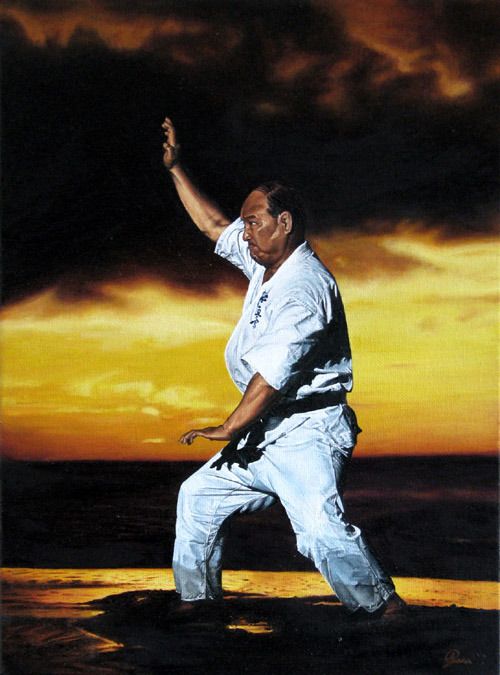

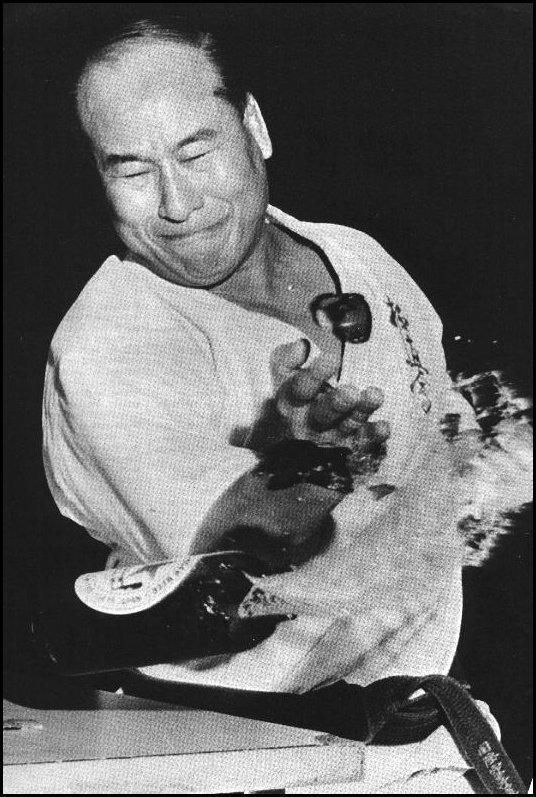

Similar to Ryu's Mas Oyama parallels, the fighting style created by the Sakazaki family in the Art of Fighting/King of Fighters series, Kyokugenryu Karate, is also itself derived from Mas Oyama's real life Kyokushin Karate.

(Left: Ryo Sakazaki. Right: Mas Oyama.)

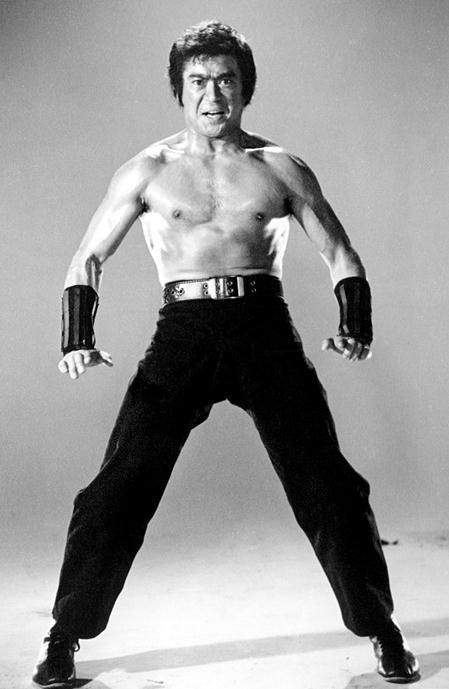

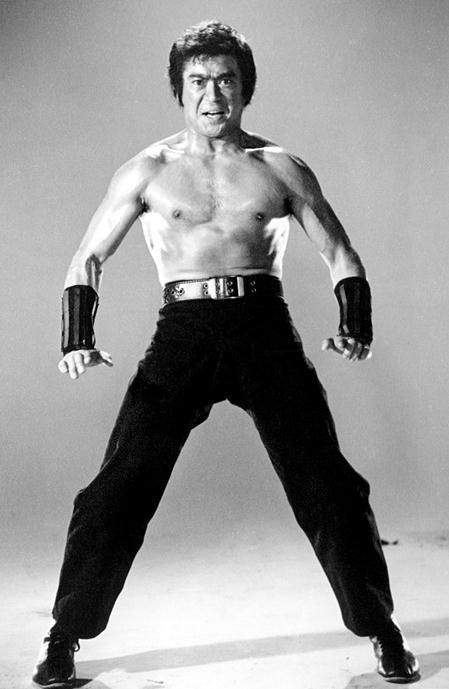

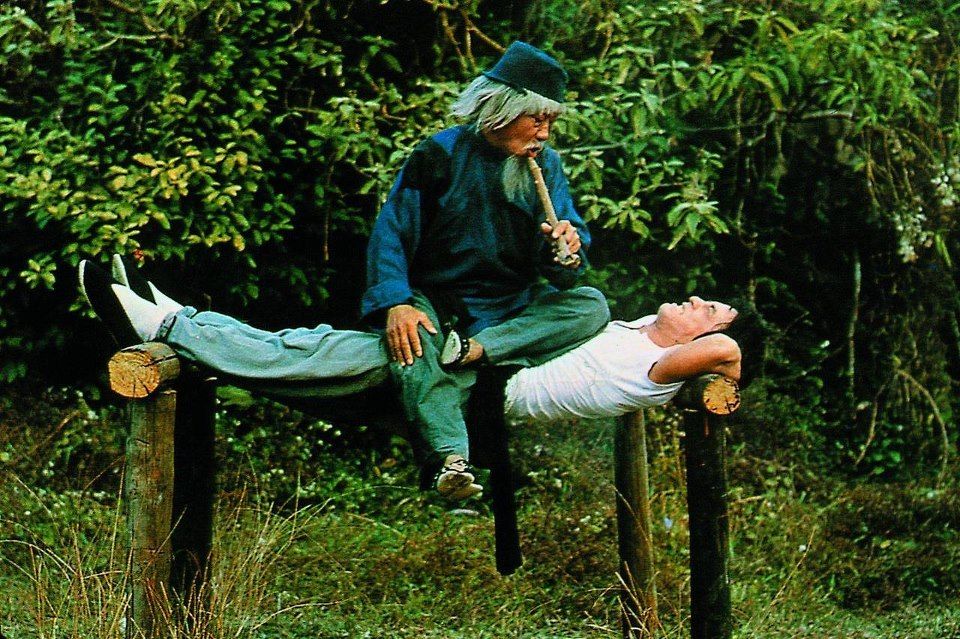

Ryo's father Takuma Sakazaki meanwhile is heavily inspired by Sonny Chiba's character Takuma Tsurugi from the (coincidentally named) “The Street Fighter” Japanese martial arts film series which was a massive and much beloved staple in American grindhouse theaters in the 70s and 80s. Chiba also studied martial arts under Mas Oyama in real life and played him in a number of films.

(A Tale of Two Takumas: Art of Fighting's Sakazaki on the left, Sonny Chiba's grindhouse icon Tsurugi on the right.)

Geese Howard also similarly owes his persona as much to stock crime villains from pulpy grindhouse films and 80s Hollywood action movies as he does from Wuxia, further blending the past with the present as was the martial arts fantasy genre tradition of the day.

Similar to many comic and manga series, the later merged King of Fighters series would be broken up into several “story arcs”, with earlier arcs focusing more on traditional Wuxia mysticism (the “Orochi saga” which centers on the resurrection of a corrupt warrior deity and the ancient martial arts clans charged with ensuring he is never awoken) and later arcs venturing more into sci fi territory (the “NESTS saga” which focuses on a secret underground syndicate who intend to manipulate the King of Fighters tournament for their own corrupt ends).

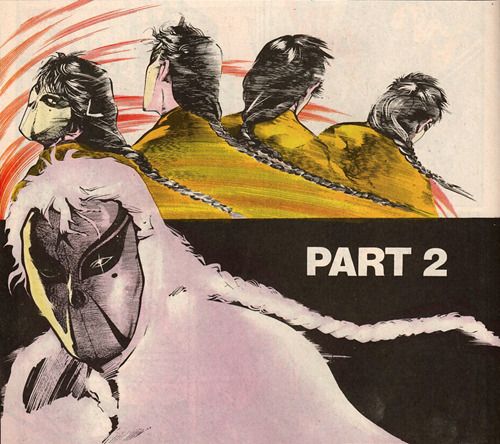

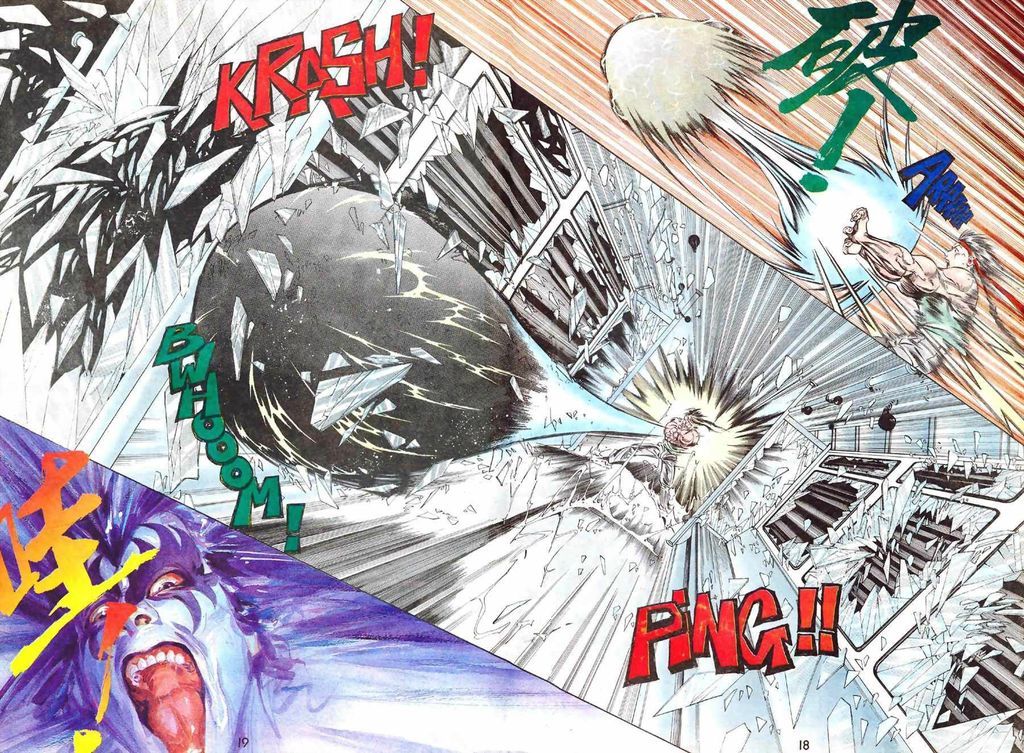

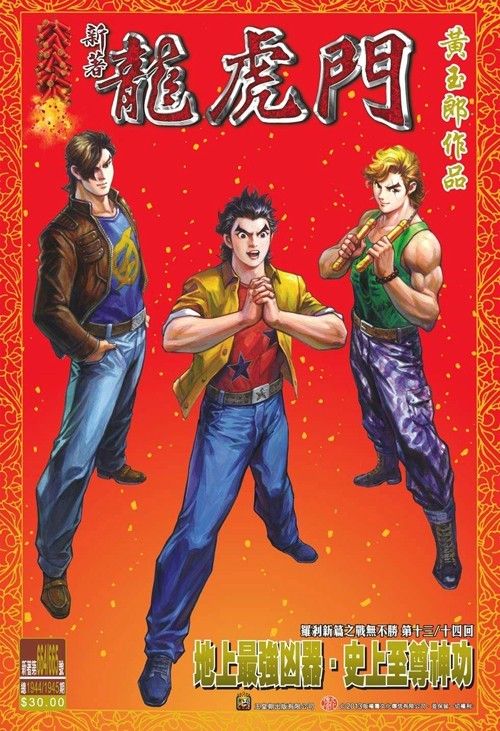

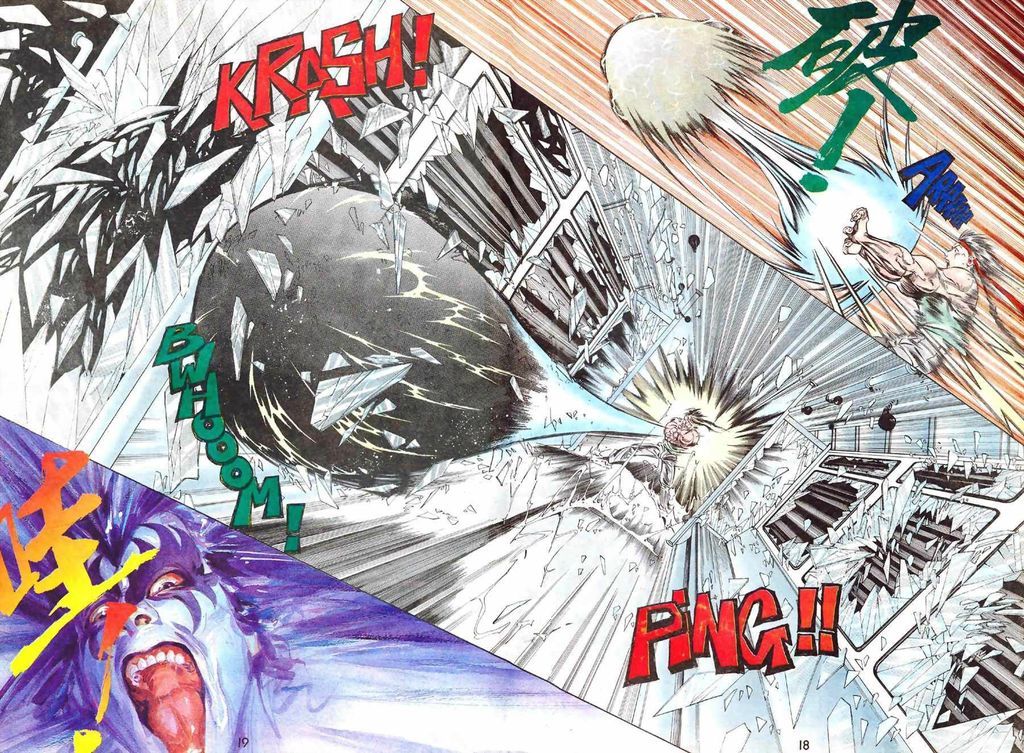

Further cementing both the Street Fighter and King of Fighters' positions as pieces of early 90s Wuxia media was their Wuxia Manhua adaptations. Street Fighter would get one in 1992 barely a year into its arcade history by none other than legendary Chinese Wuxia Manhua publisher Jademan Comics.

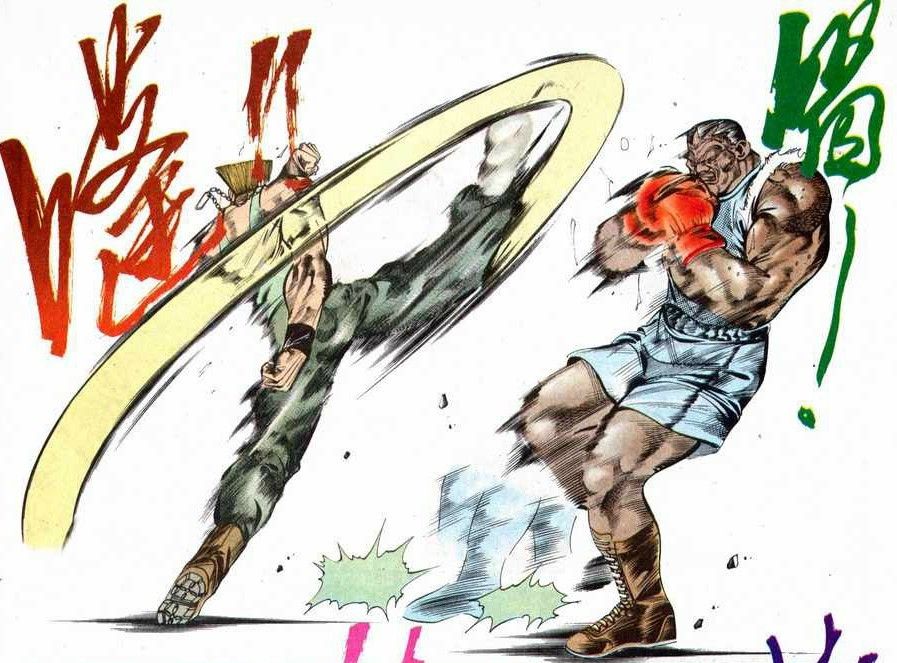

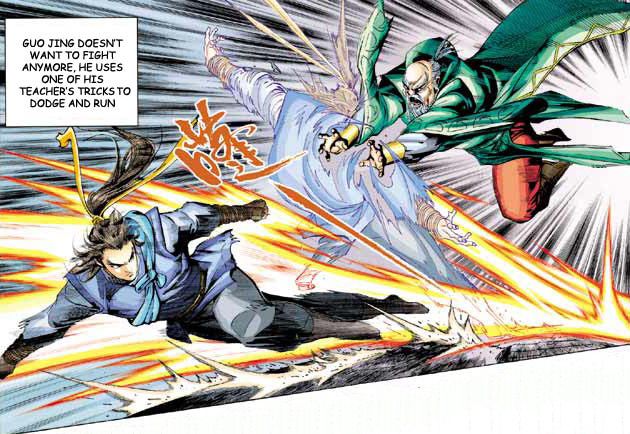

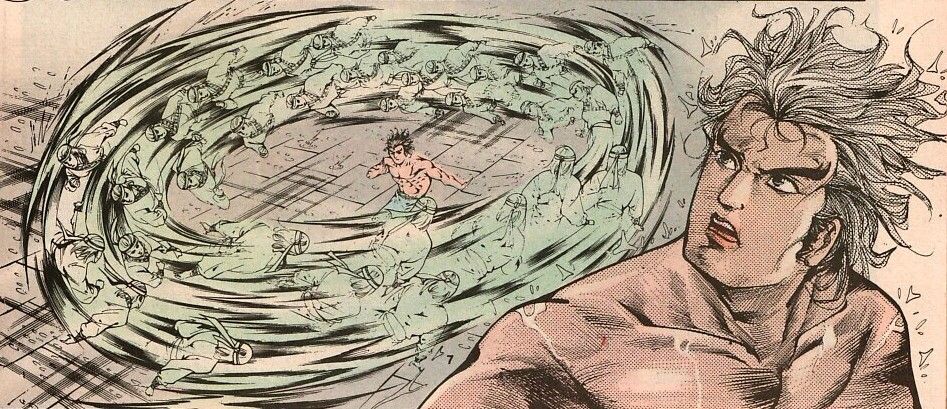

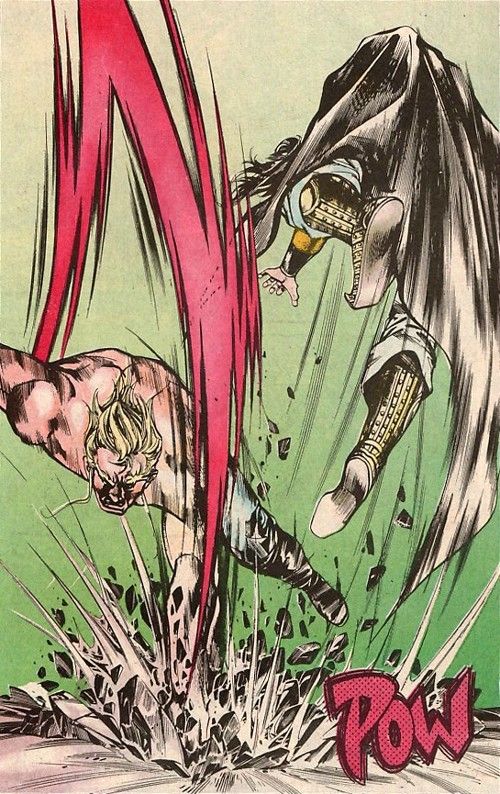

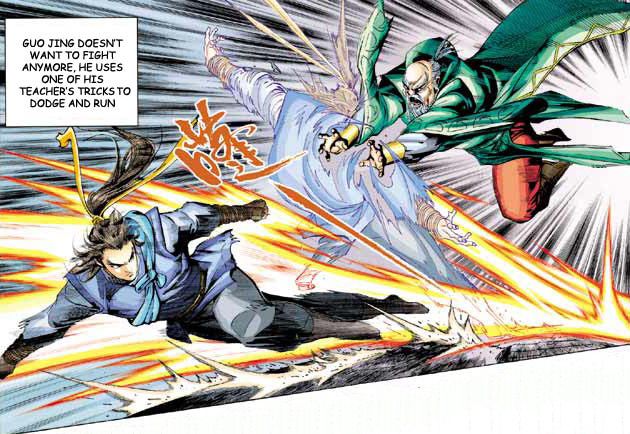

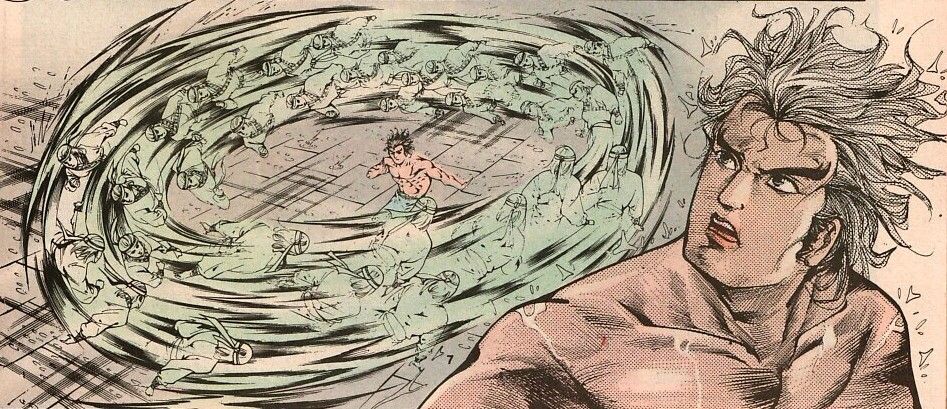

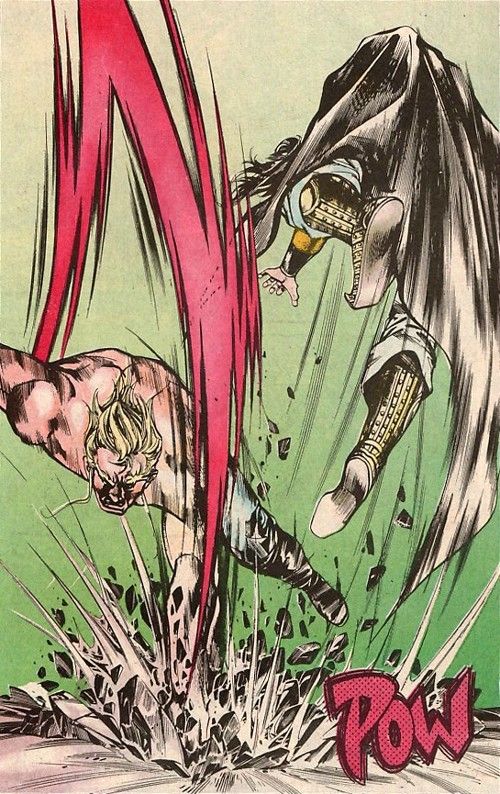

Written and drawn by Xu Jing Chen, the Street Fighter II manhua is gorgeously illustrated and as absolutely early 90s bonkers as genre-blended Wuxia of the era gets, with massive all out free for alls between the incredibly powerful Wulin warriors of the Street Fighter world amidst batshit science fiction subplots centering on evil clone dopplegangers and other such balls to the wall madness.

King of Fighters meanwhile would get a Wuxia manhua much later on in the 90s with Andy Seto's King of Fighters: Zillion followed by numerous sequel series which all ran up through the early to mid 2000s, including a few crossovers with Street Fighter.

Its not at all an exaggeration to say that literally the entire 90s fighting game boom owes a LOT of its existence to Wuxia, particularly the hyper manic crazed genre-busting incarnation that the genre had taken across much of the 80s and early 90s. Very close to almost every major 2D arcade fighting game title released in that time period can be seen, to one extent or another, as essentially a completely off the wall outrageous Hong Kong Wuxia film or manhua in video game form.

By the end of the 80s and dawn of the 90s, Hong Kong cinema as a whole (and Wuxia along with it) had grown MASSIVELY in popularity all across the world. Including even North America. And this time it wouldn't just be the grindhouses and ghettos getting a taste for it (the grindhouse theater industry indeed was fading fast by the late 80s and would be gone entirely by the very early 90s, largely being made obsolete and replaced by the straight to video/VHS industry).

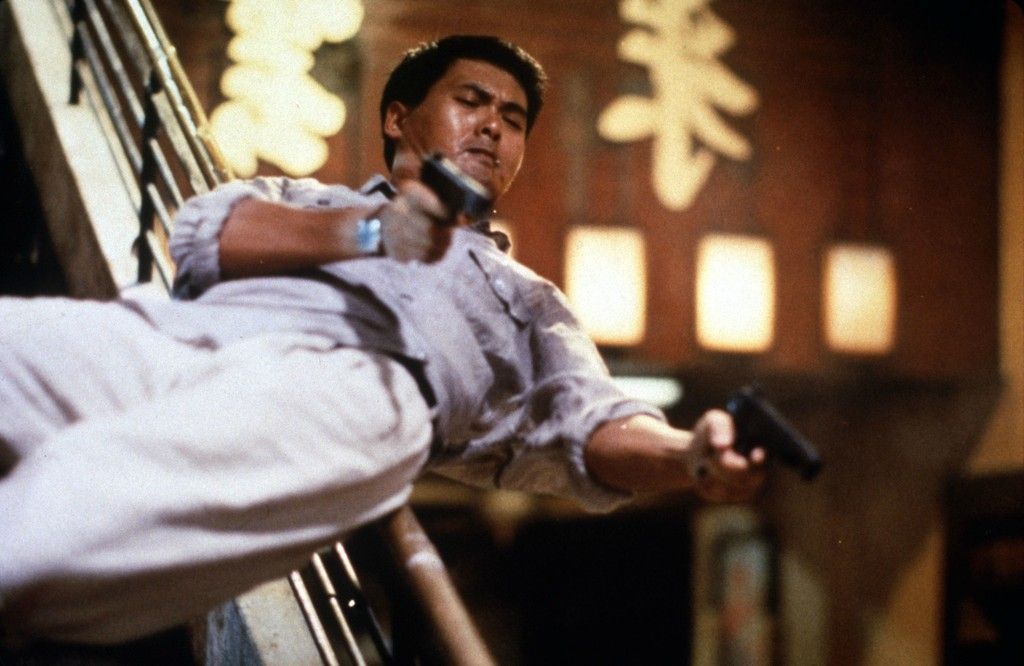

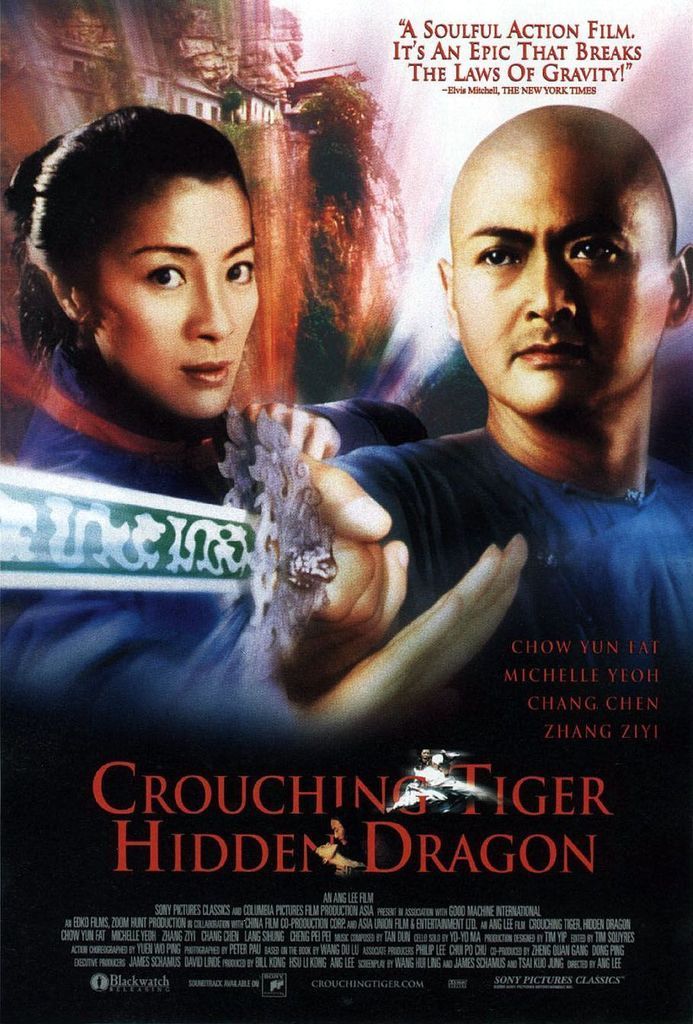

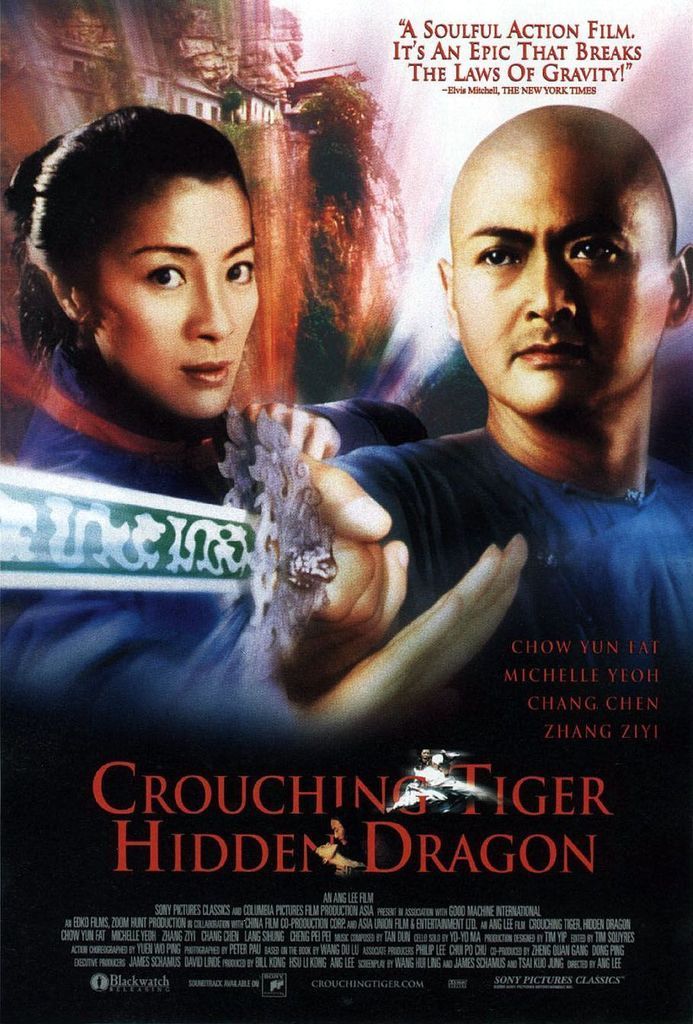

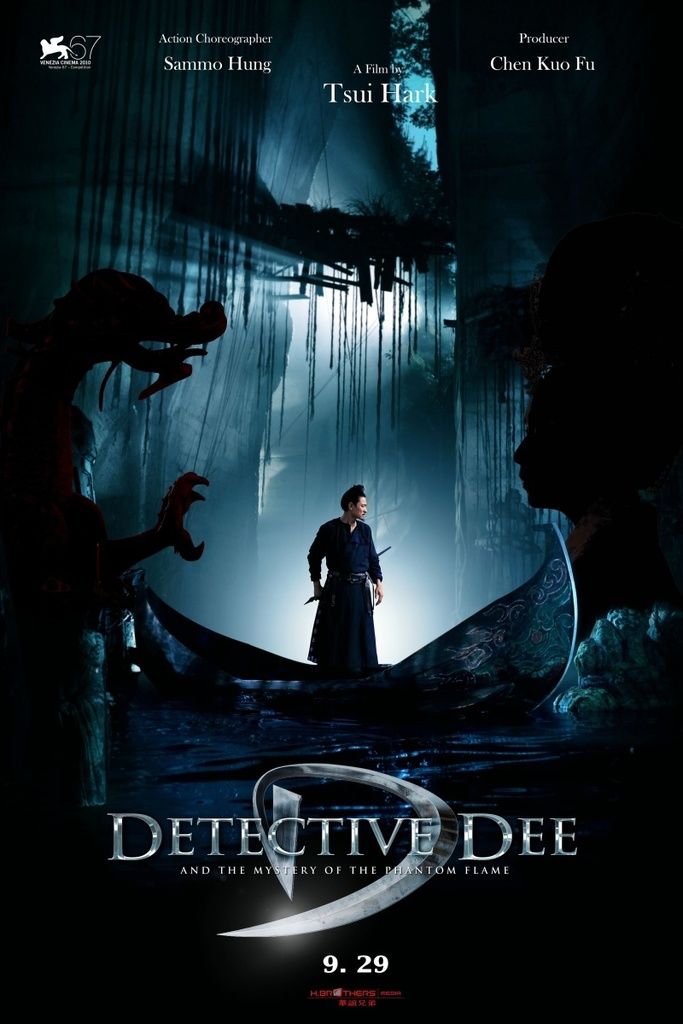

Spurred on largely by the output of John Woo and Tsui Hark, Hong Kong films - particularly Heroic Bloodshed (operatically melodramatic and excessively violent Chinese mob/Triad epics), drama, comedy, and martial arts/Wuxia films - absolutely EXPLODED amongst the so called “Generation X Grunge/Slacker” culture of the time.

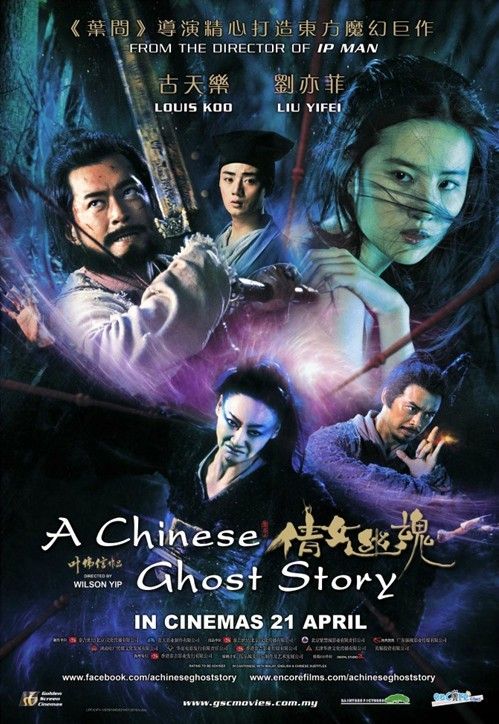

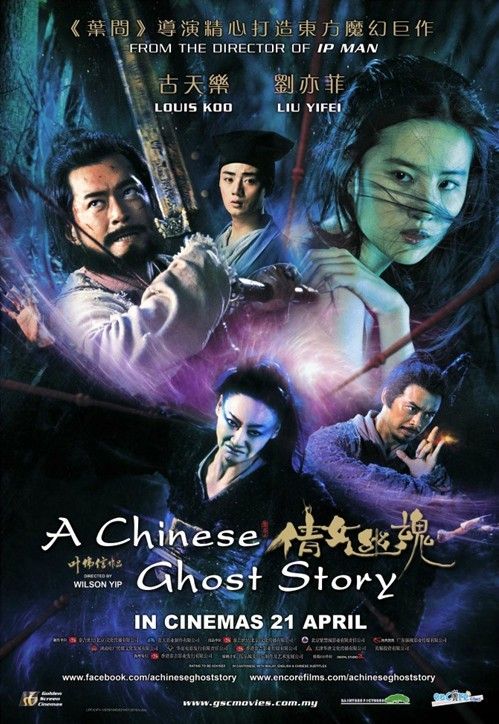

Amongst the major Wuxia titles of the time, A Chinese Ghost Story, Hark's wild remake of the King Hu classic Dragon Gate Inn, and the Swordsman/Smiling Proud Wanderer films were particularly huge amongst teens and 20-somethings of the time, many of whom were also (as noted earlier) into and collected anime and manga as well. Due to the vast use of bootleg VHS tape trading used to gain access to both unlicensed anime as well as HK films, a tremendous degree of overlap formed between the two fandoms, intertwining them closely together for a good number of years throughout much of the 90s.

Particularly due to the prevalence of wacky, dementedly over the top Mo Lei Tau humor, a large number of HK action and Wuxia films were seen by many Western fans at the time as essentially live action anime. Coupled with the popularity of similarly themed 2D fighting games and this also fueled into the popularity of titles like Dragon Ball, Yu Yu Hakusho, Hokuto no Ken, and Ranma ½ at the time.

Being Shonen titles aimed at a much younger audience in their native Japan, they tended to glaringly stick out amongst a largely Seinen/Gekiga dominated Western anime and manga landscape (well, maybe less so Hokuto no Ken) of the late 80s/early 90s that otherwise routinely ignored and cared very little for a great deal of Shonen. But the numerous similarities with over-exaggerated and manic energy violent/comedic Hong Kong martial arts/Wuxia films won them a fairly sizable fanbase amongst an older audience who were also plugged into the weird genre-bending sensibilities of the then-still thriving and ubiquitously popular Hong Kong New Wave.

(A very large chunk of late 80s/early 90s Western anime & manga fandom gravitated to the medium on the strength of envelope pushing strictly adult-aimed Seinen titles with a heavy Gekiga visual bent to them, and were typically unmoved by and disinterested in most child-friendly Shonen due to them being seen as largely redundant to a culture that already has long had more than its share of child-aimed animated works for countless years. Certain titles like Ranma, YYH, and DBZ however slipped their way between the cracks of this distinction due to their overt similarities with manically bizarre Hong Kong Wuxia/supernatural martial arts films that were also popular at the time.)

At the same time, while the number of officially licensed Hong Kong films and Japanese anime & manga continued to grow along with bootleg trading of many others that were yet to be licensed, popular Hong Kong Wuxia Manhua publisher Jademan Comics would dive into this growing new North American market during the late 80s and early 90s with officially translated and licensed reprints of many of their own classic Wuxia Manhua, including Ma Wing Shing's seminal Chinese Hero series (published here under the titles of Tales of the Blood Sword and Blood Sword Dynasty), Oriental Heroes, and numerous others, thus further stoking the popularity and visibility of Wuxia among fans at the time.

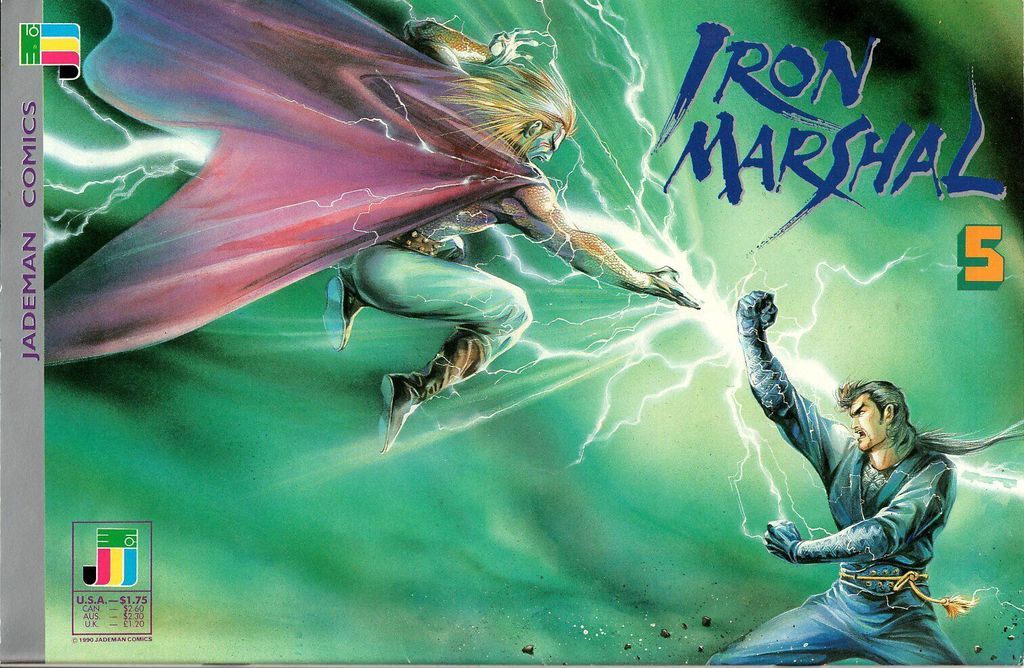

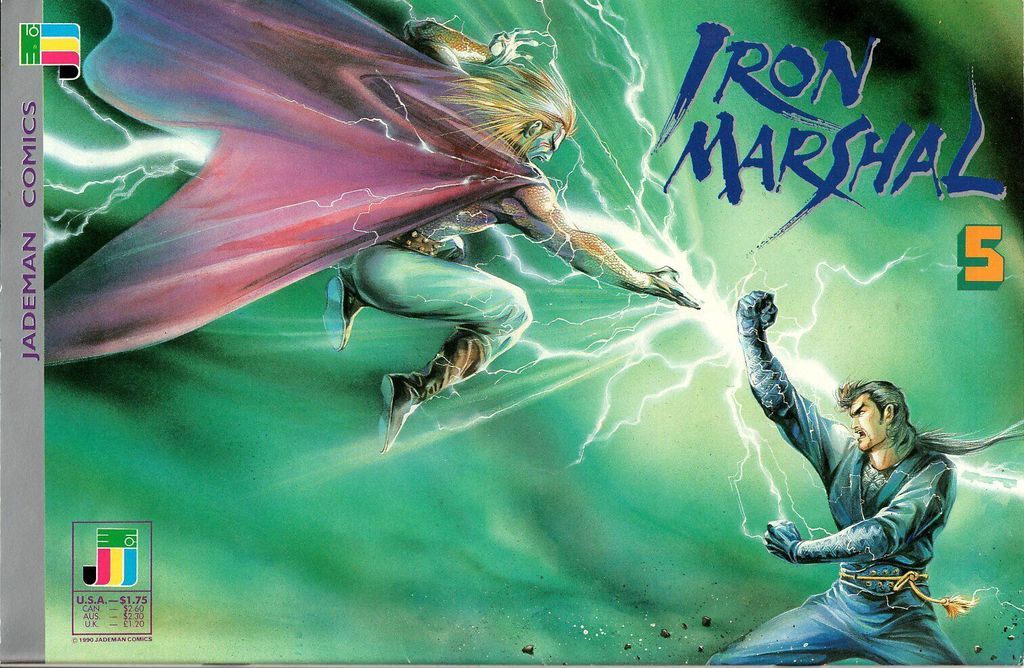

(An official North American Jademan printing of the 5th chapter of the Wuxia manhua Iron Marshal by Lee Chi Ching, cover dated November 1990.)

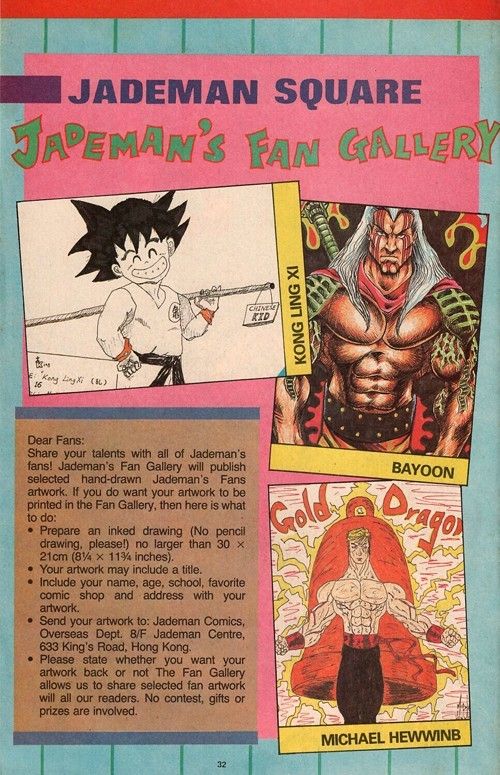

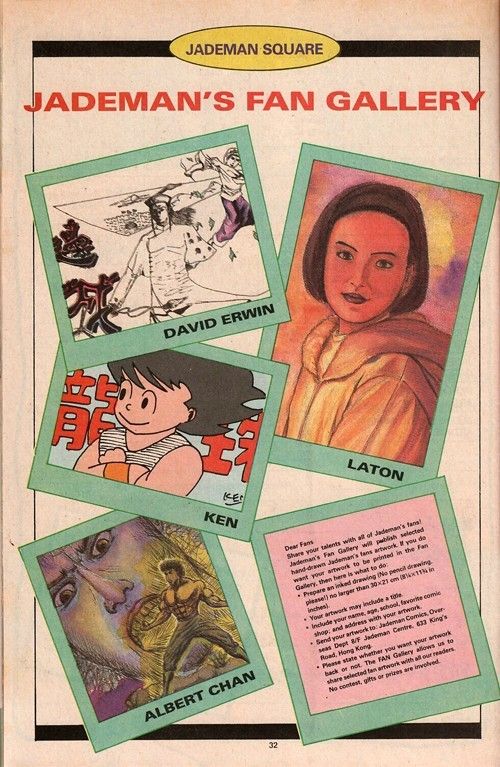

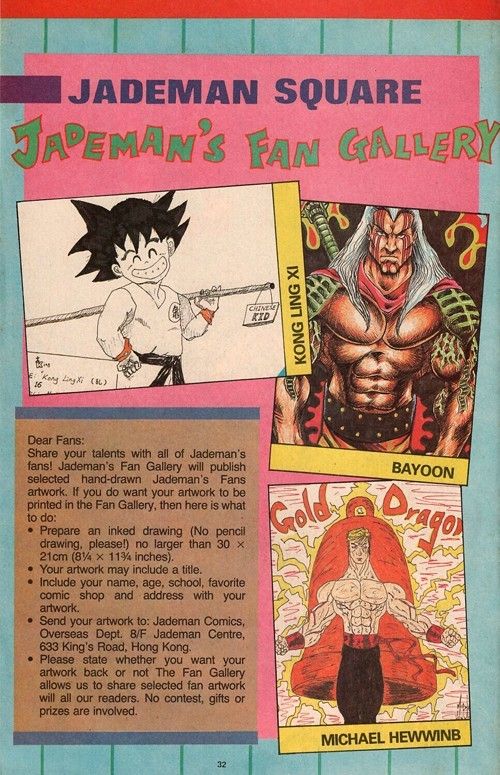

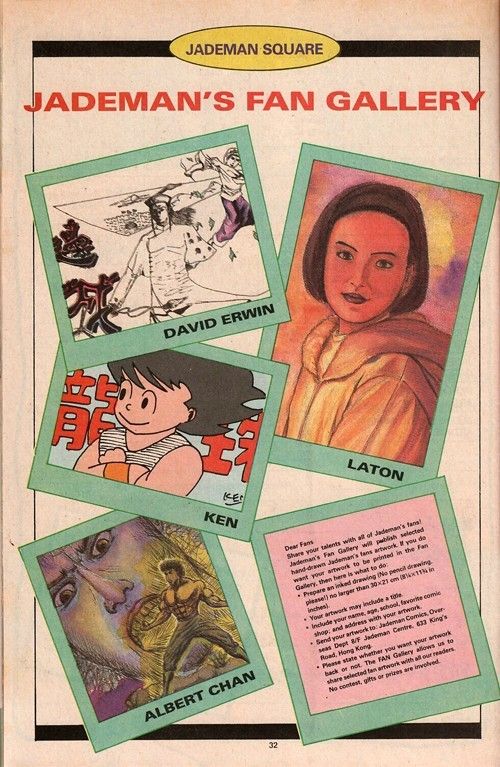

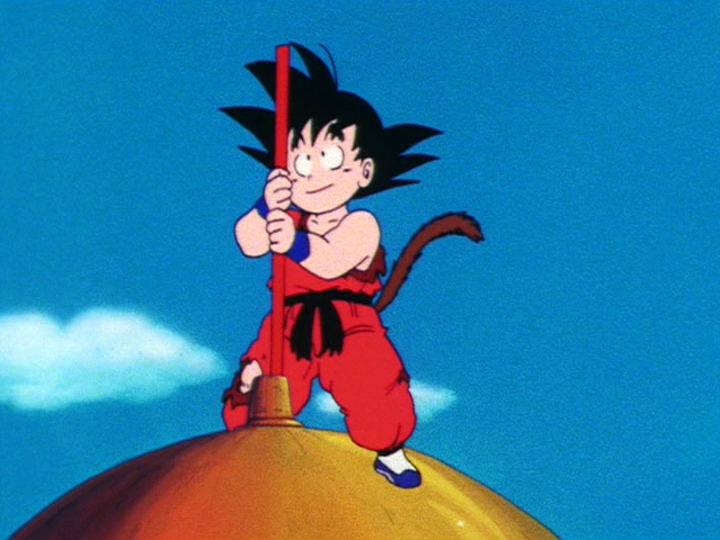

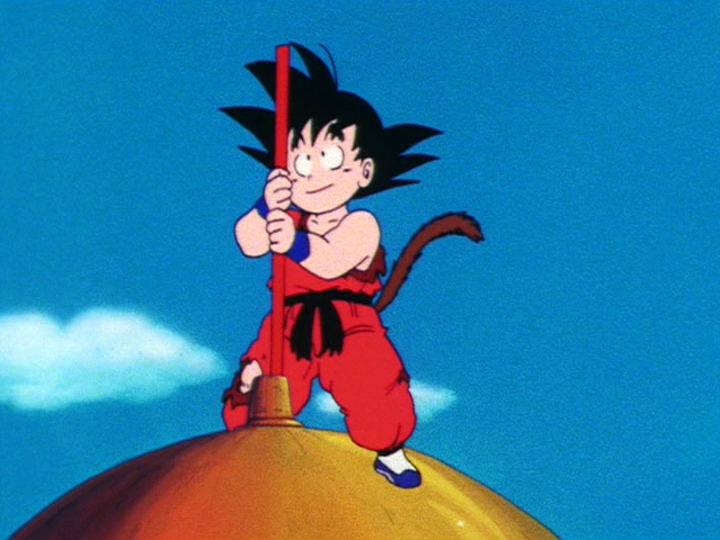

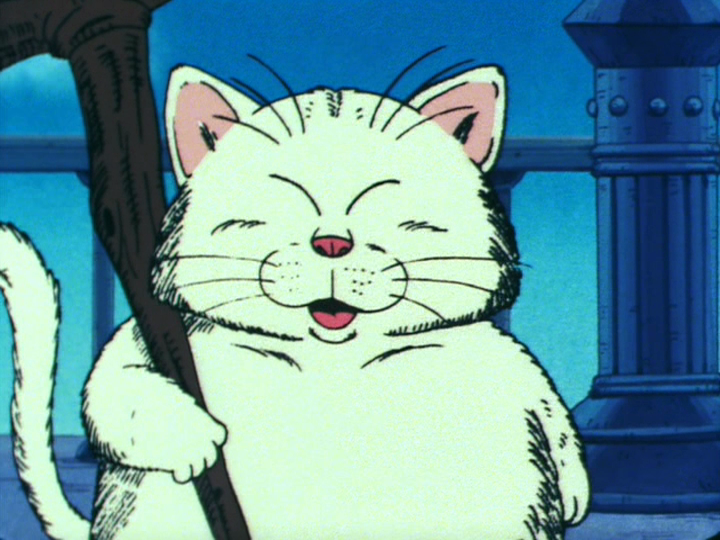

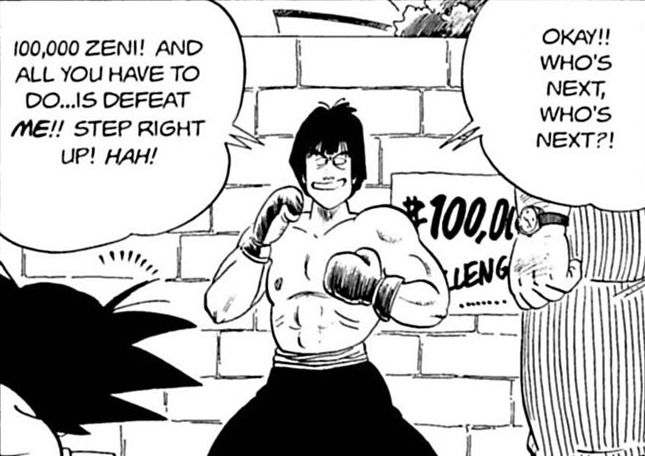

(Some American Jademan issues, as with their Chinese counterparts, also had a section in the back for submitted fan art. You may recognize a certain distinctively hair-styled monkey boy who made frequent appearances in these.)

It cannot possibly be overstated what a VASTLY diametrically different world the Western anime/manga landscape and fandom was in the early-most 90s. While there were definitely still some awkward, super dorky types that one would view as traditionally Otaku, there was also a massive number of flannel and Doc Marten-clad stoners and skater punks that were likewise a huge part of the fanbase as well back then. Their range of interests tended to be a LOT broader than just solely anime and manga, which included all kinds of supremely strange and envelope pushing underground comics and foreign movies... like movies where Chi wielding ancient kung fu mystics go toe to toe with time hopping alien cyborgs from Mars, or what have you.

(Portrait of a typical early 90s American Wuxia/anime fan. As represented here by Floyd from True Romance for... reasons.)

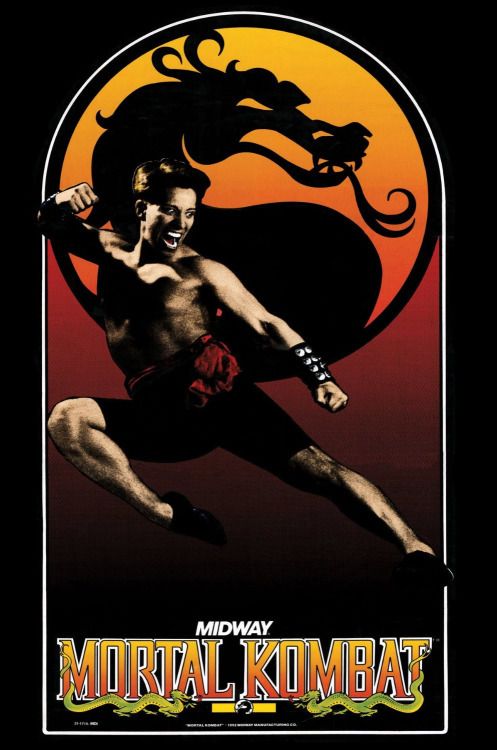

This particular cultural stew of cynical, disaffected punk rock teens latching onto hyper violent martial arts films and whimsical Chinese mysticism along with 2D arcade fighting games with similar themes and motifs spurred on yet another massive and iconic early 90s cultural touchstone amongst the youth of the time, one that was not only made for but also made by EXACTLY the sort of Nirvana-era freaks and weirdos mentioned above.

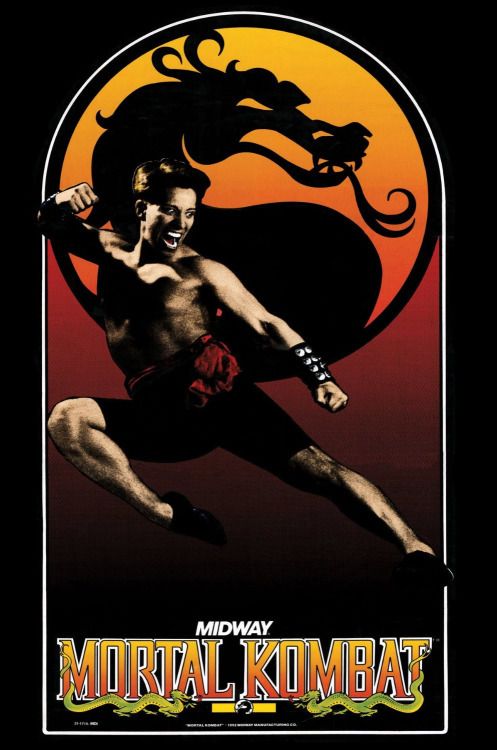

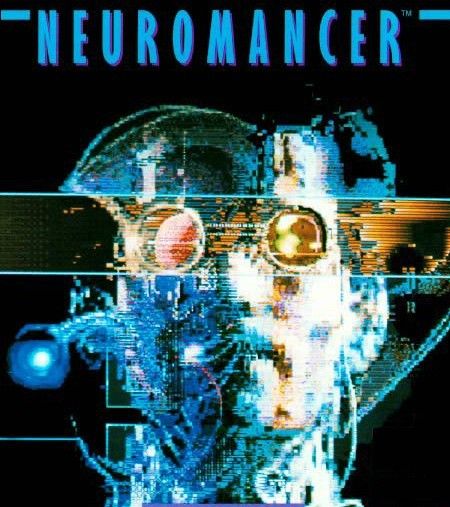

”Test Your Might”

Oh yeah.

Mortal Kombat is the utmost essence of early 90s American Wuxia fandom personified as an arcade fighting game. Created by Ed Boon and John Tobias, who back then were still fresh into their early 20s, where Street Fighter was a 2D fighting arcade game embodiment of the off its meds bugfuck insanity that Wuxia had become at the time made by Japanese people who were a great deal closer in cultural proximity to its root source, Mortal Kombat was very much the same, except made by a couple of over-enthusiastic Chicago natives who were VASTLY further removed from the cultural origin point and who had, like most of us American fans at the time, largely absorbed all this magical kung fu wackiness through shitty degraded VHS tapes with horrendously mangled subtitles or dubbing; side by side along with countless other gore and viscera splattered 80s horror and action movies.

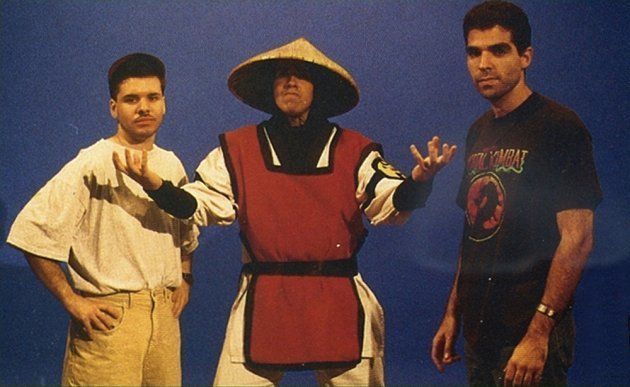

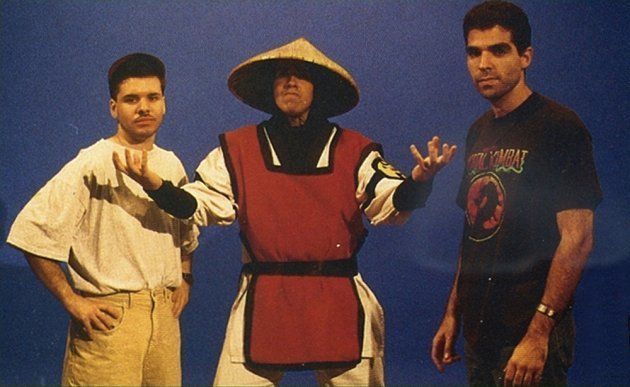

(Left: John Tobias. Right: Ed Boon. Center: Carlos Pesina, the martial artist who modeled for Raiden's digitized sprite in the first two MK games.)

On the artistic/lore/creative end of things, the VAST majority of the credit for MK turning out the way it did really goes to John Tobias, who was also a damned talented comic book illustrator as well. Drawing from an incredibly broad range of global influences, Tobias has made very little secret of Mortal Kombat's Wuxia origins, citing numerous films of the time as major influences on the end product.

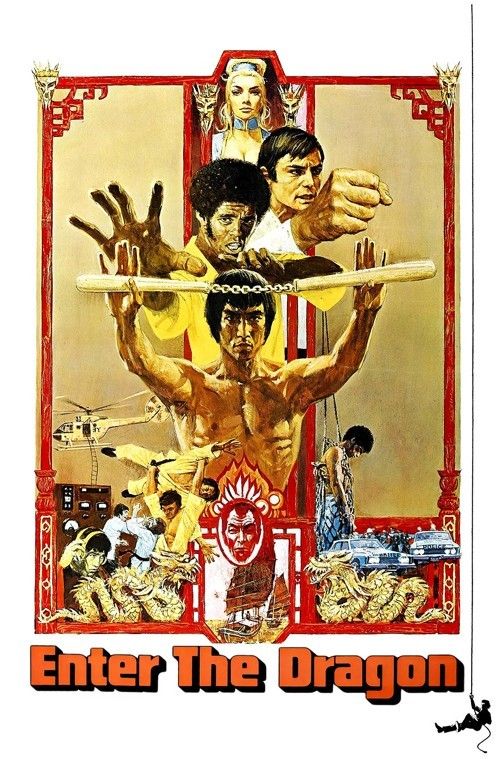

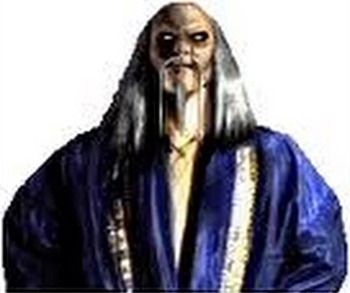

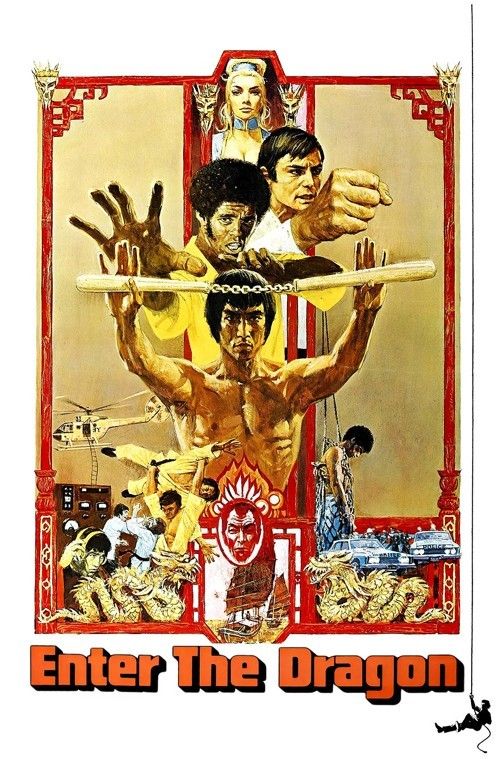

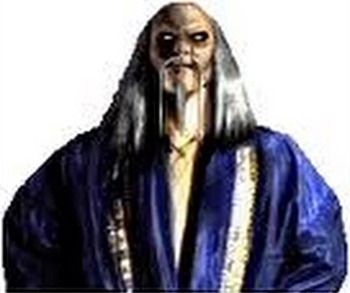

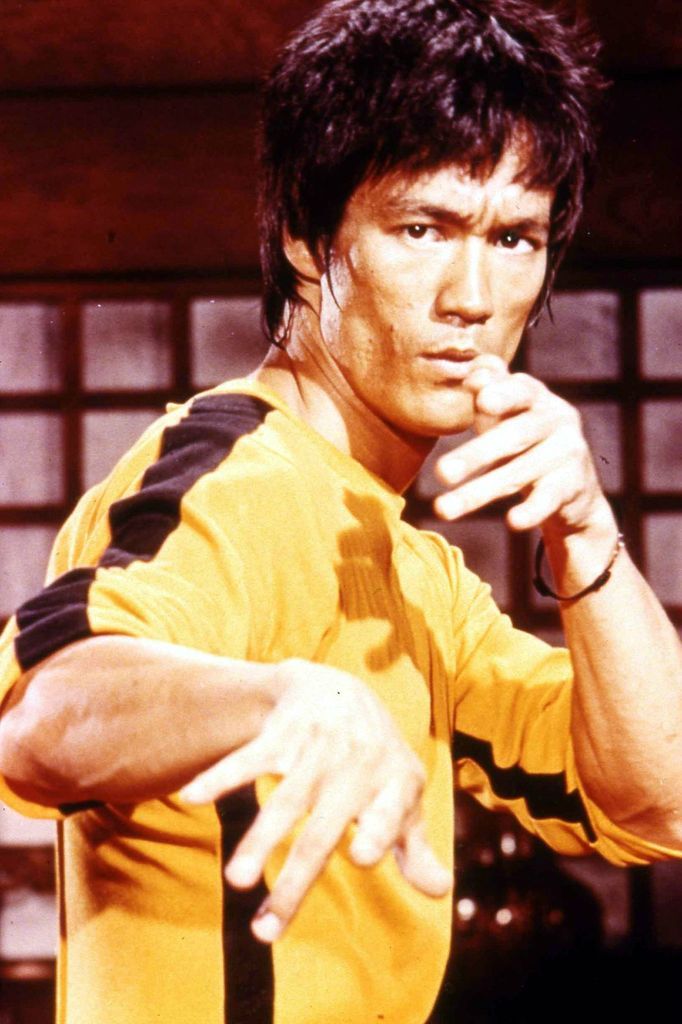

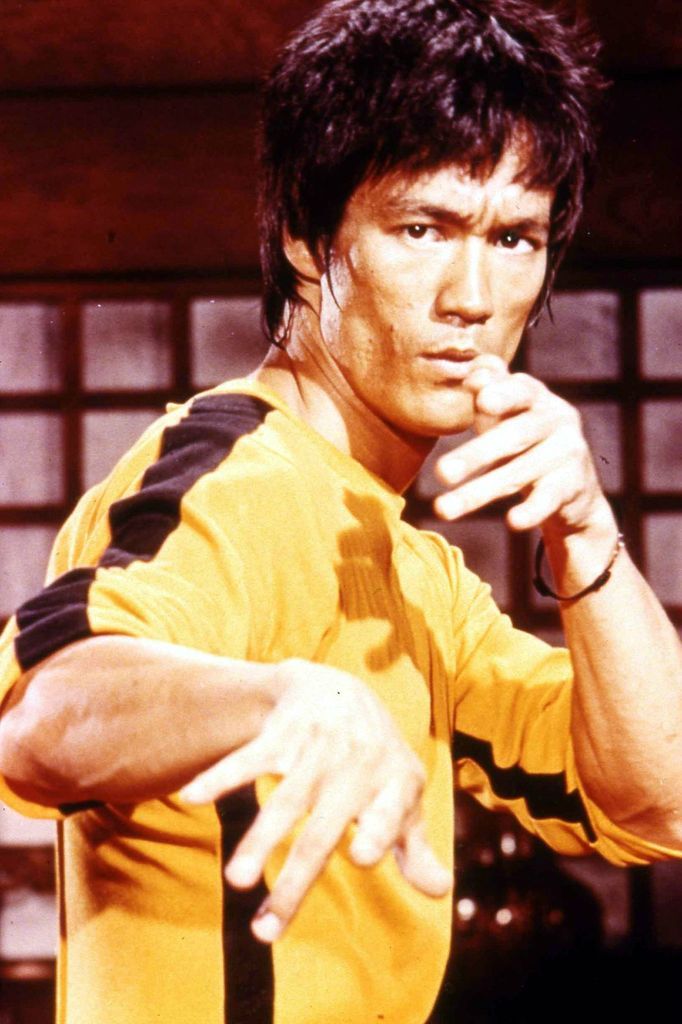

The two most obvious ones right off the bat are Enter the Dragon and Big Trouble in Little China. Chinese sorcerer antagonist Shang Tsung is clearly in many ways a dead ringer for Big Trouble's Lo Pan (both cursed Chinese mystics trying to appease angered deities), while Raiden's character design is famously copied and pasted from Lo Pan's “Three Storms” minions.

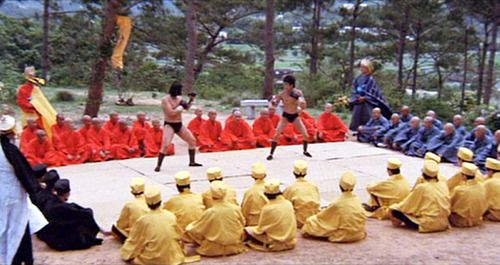

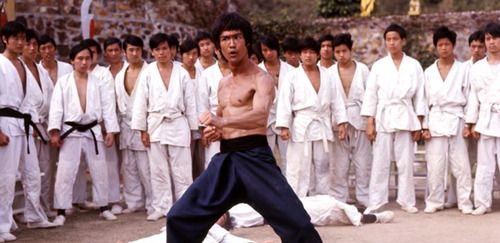

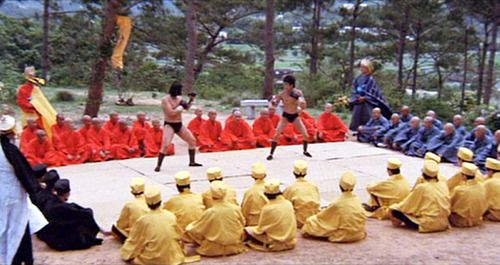

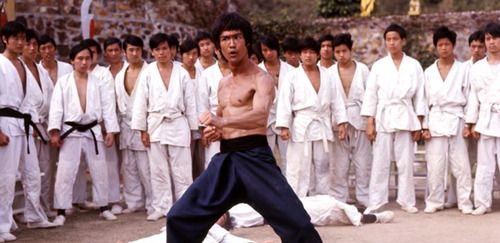

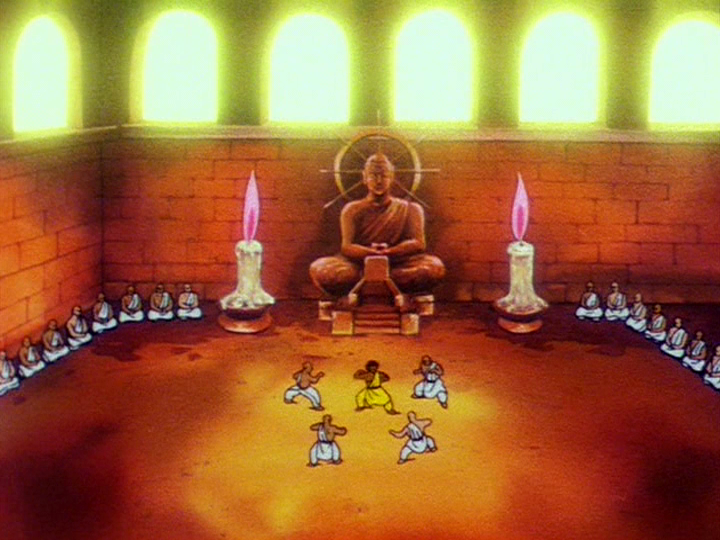

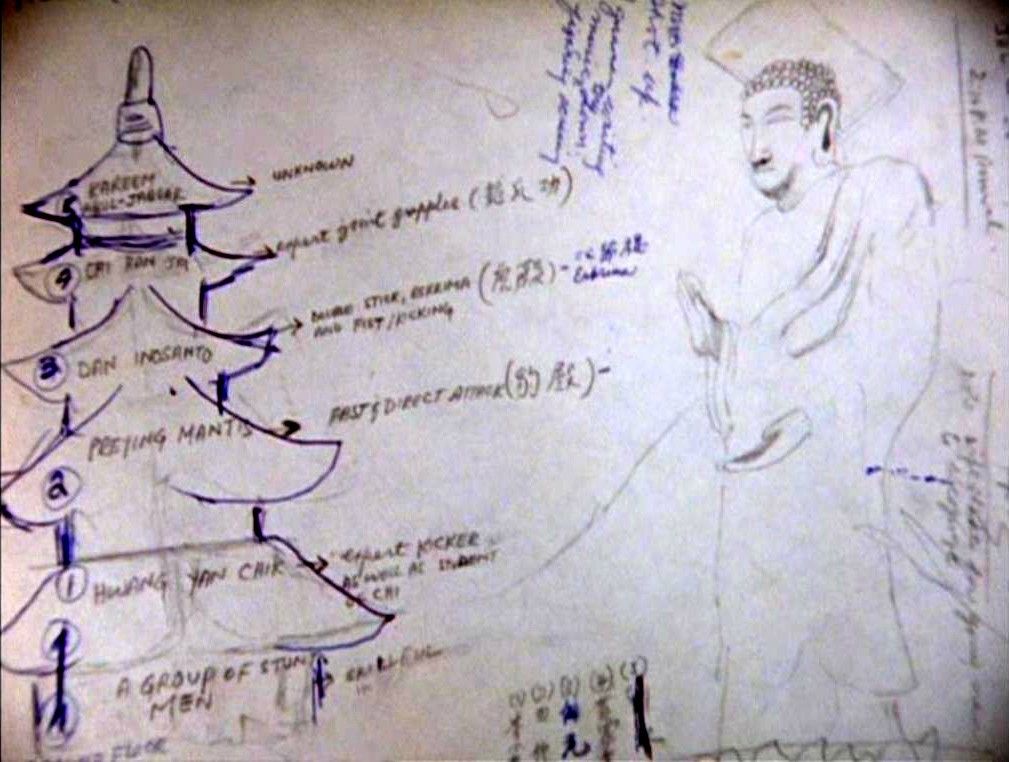

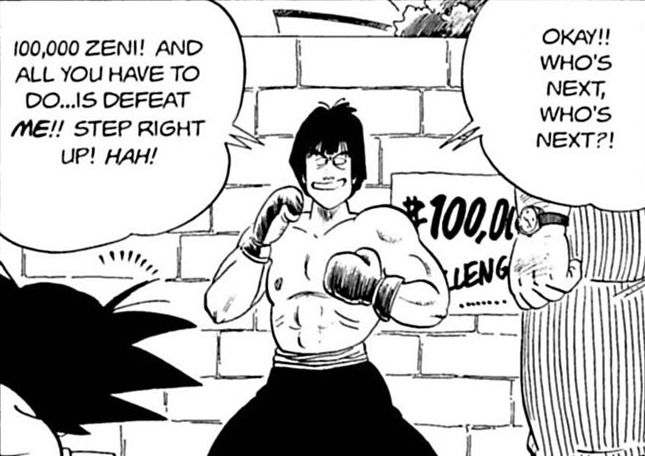

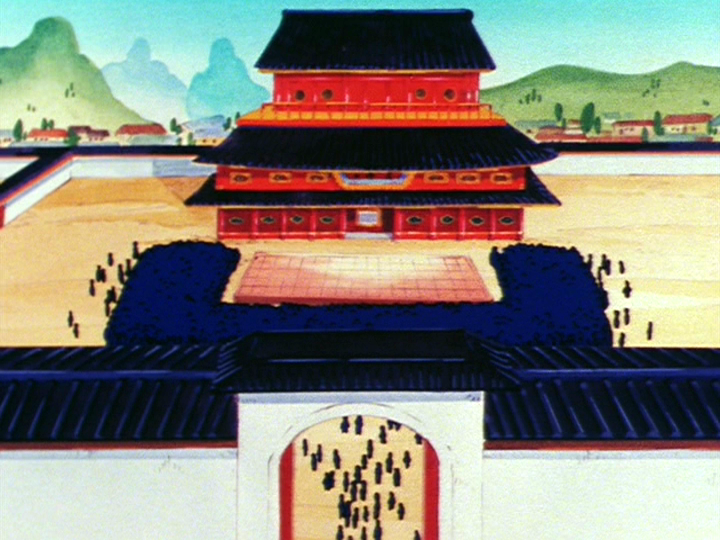

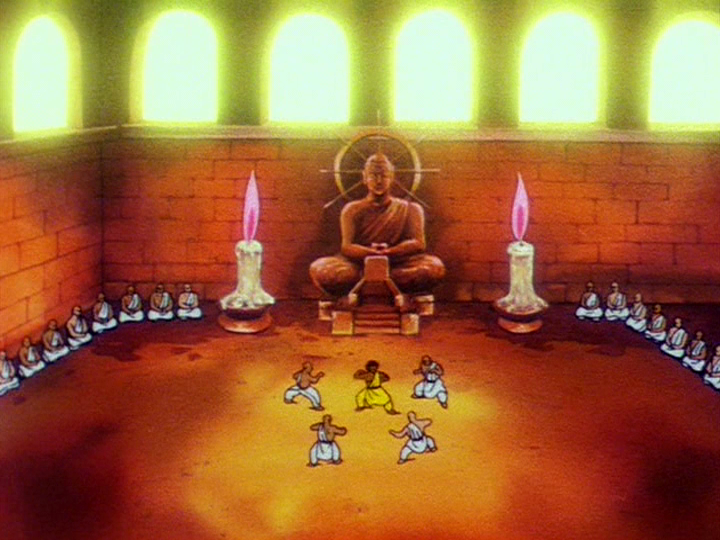

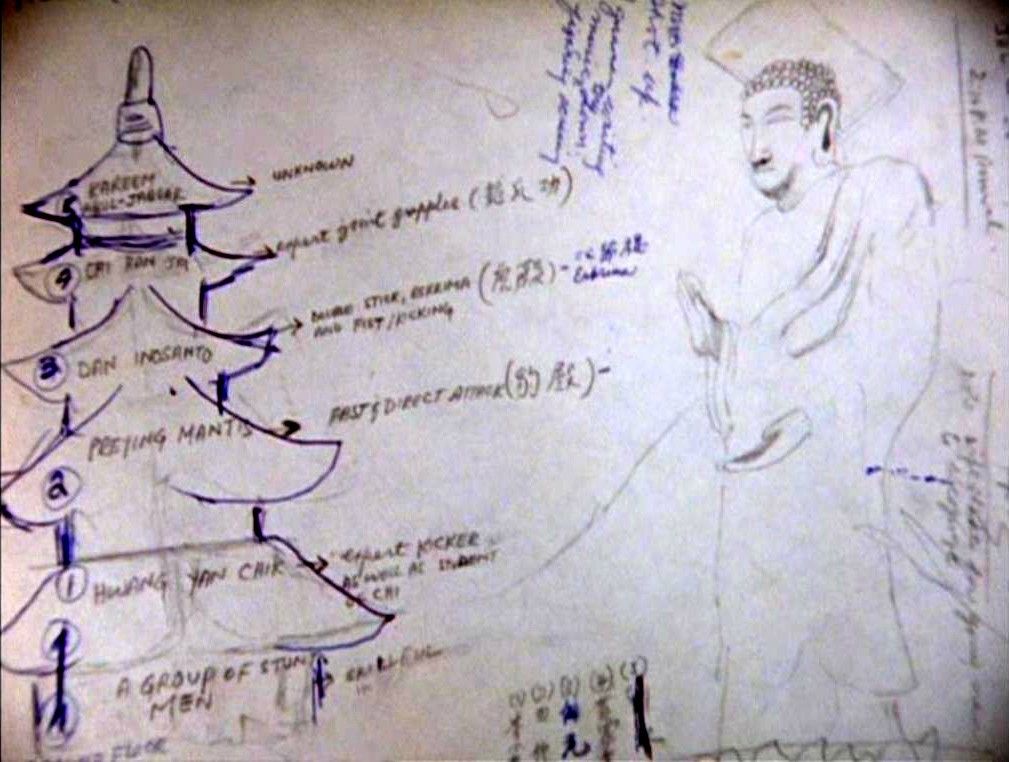

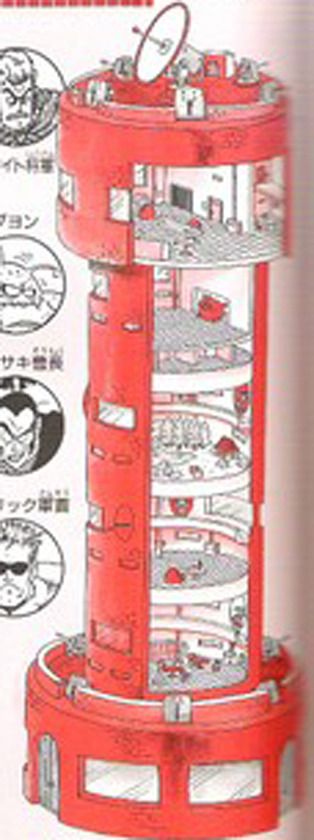

Enter the Dragon feeds into it via the first MK's plot of a Shaolin martial arts tournament held on a small, private island hosted and owned by the main villain who has taken over and corrupted the tournament for his own ends, with a Bruce Lee lookalike (Liu Kang) as the main Shaolin hero who enters in order to take the tournament back from the villain and restore its honor on behalf of his temple.

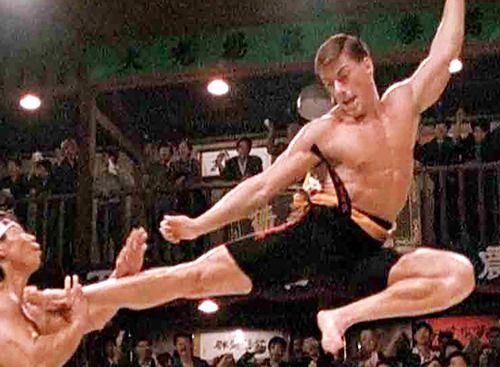

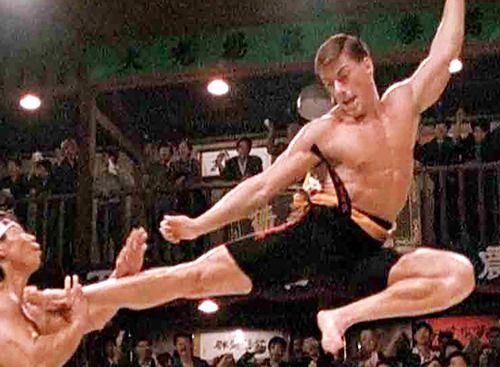

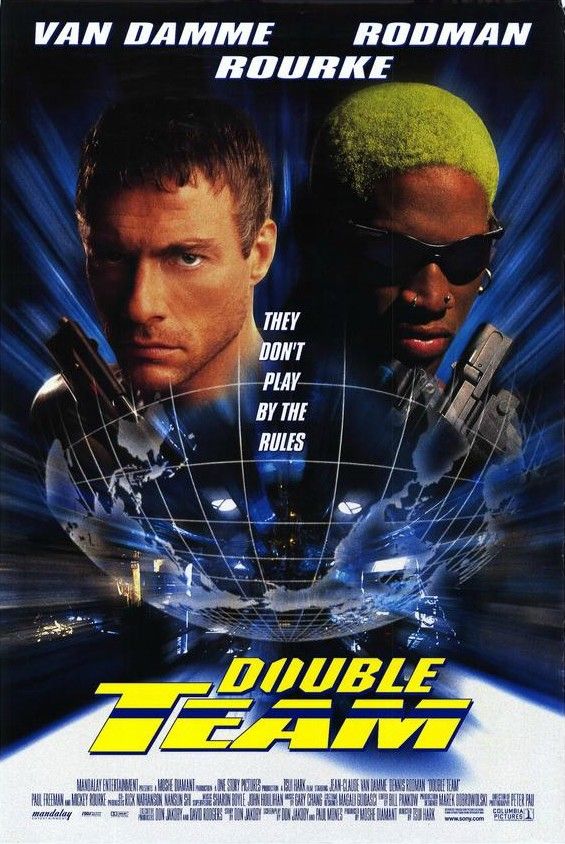

Also playing into it is the 80s Van Damme film Blood Sport, with the tournament there being a “to the death” gore soaked bloodbath where fighters are routinely and graphically maimed and killed in each match, along with the MK character Johnny Cage being a dead ringer for Van Damme's Frank Dux in both his costume and various fighting moves, particularly the famous “split punch”.

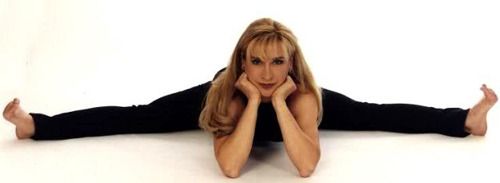

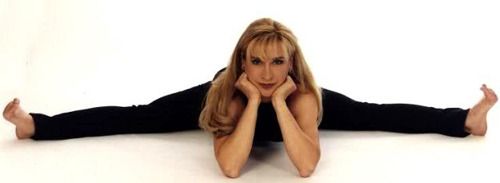

Sonya Blade is also heavily influenced by Cynthia Rothrock, one of the most popular female martial arts action stars of the 80s and early 90s who also starred in a number of Hong Kong martial arts films.

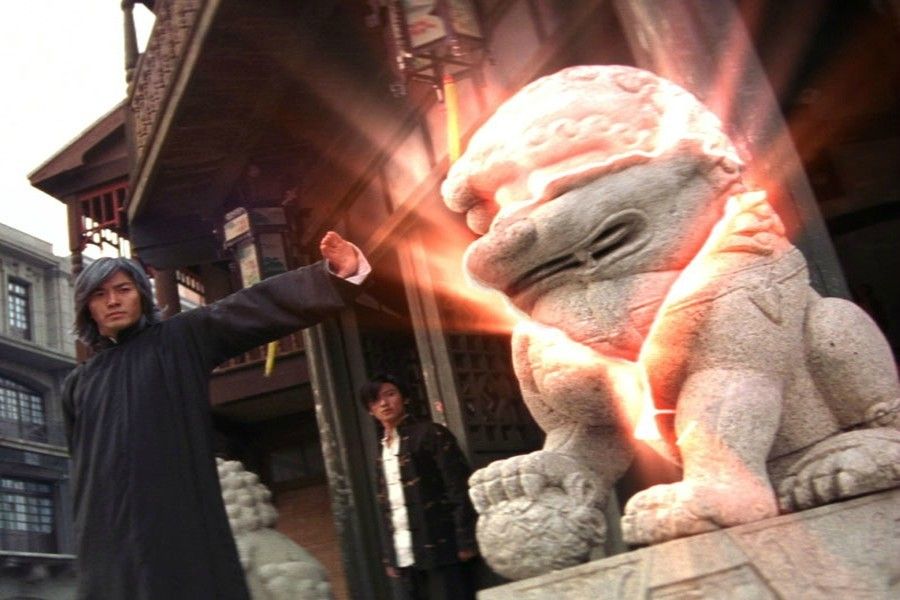

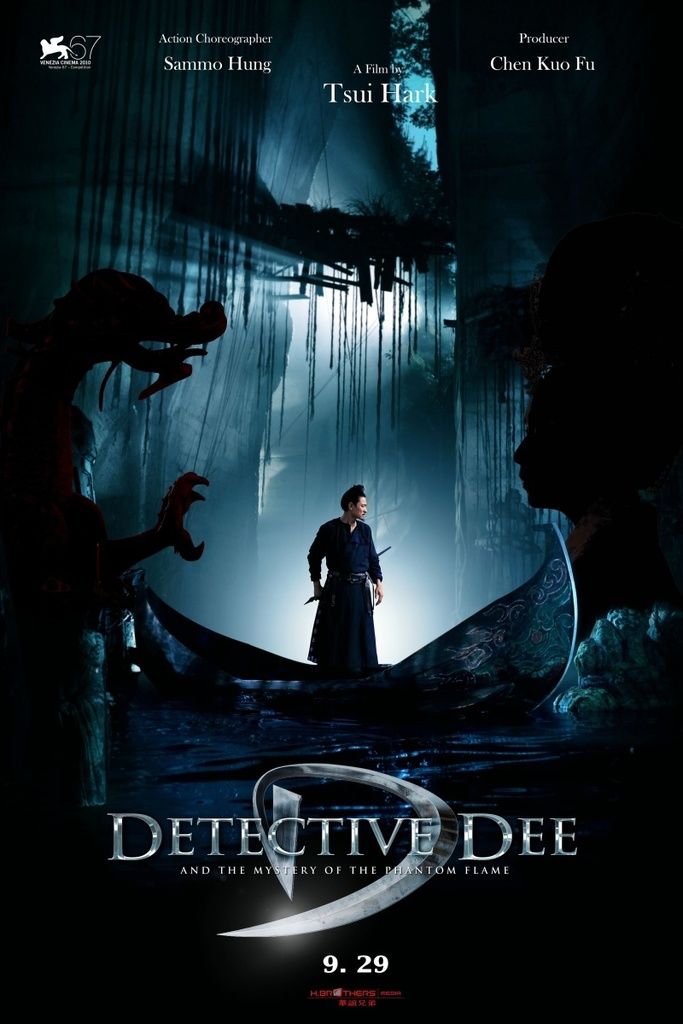

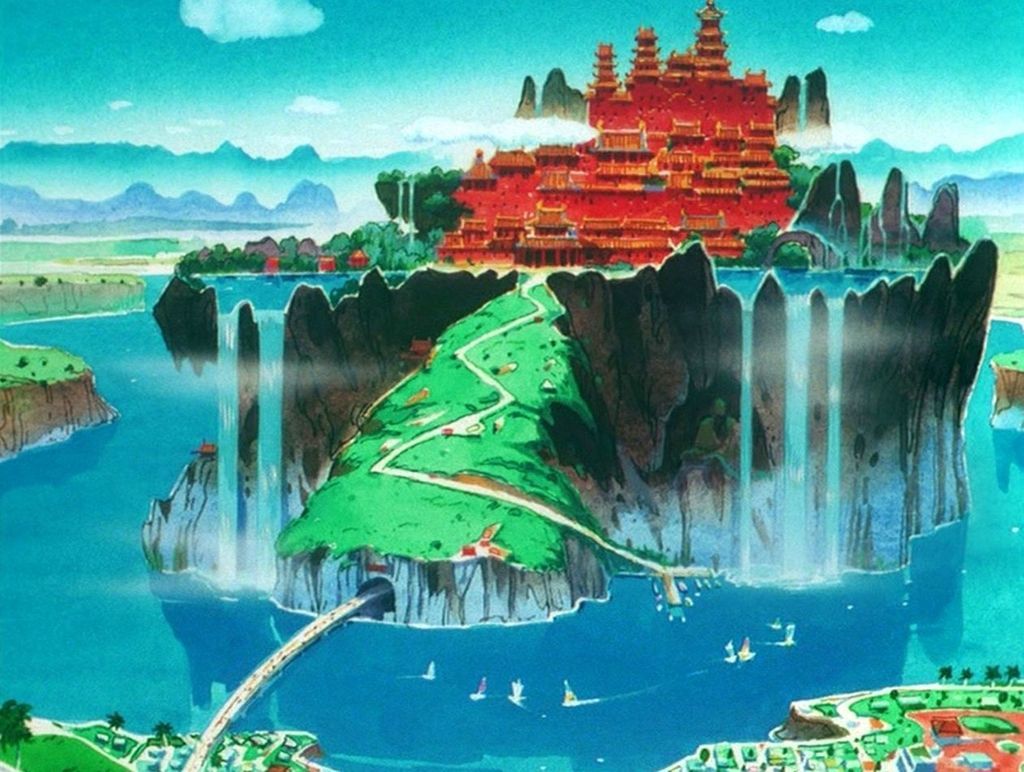

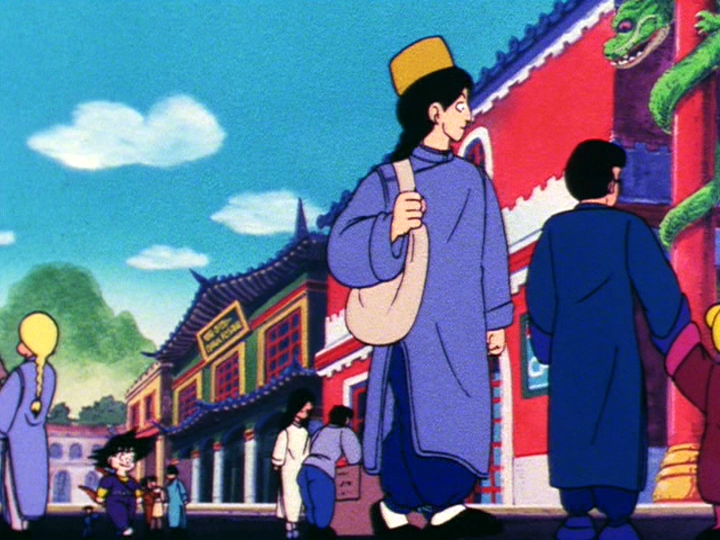

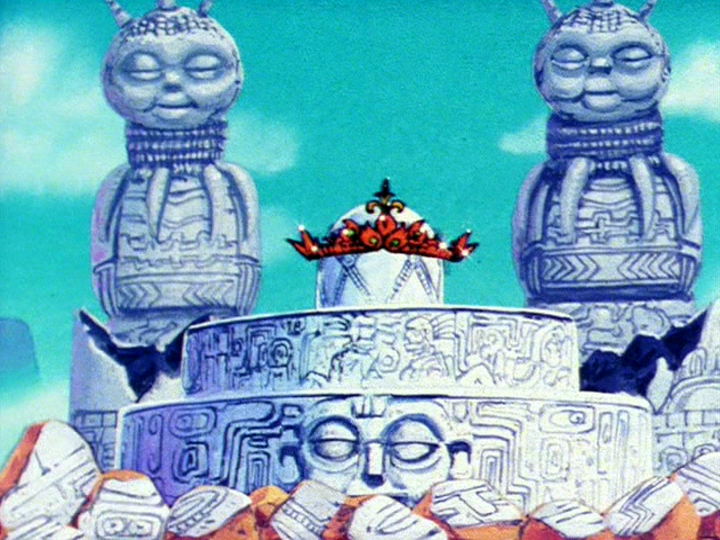

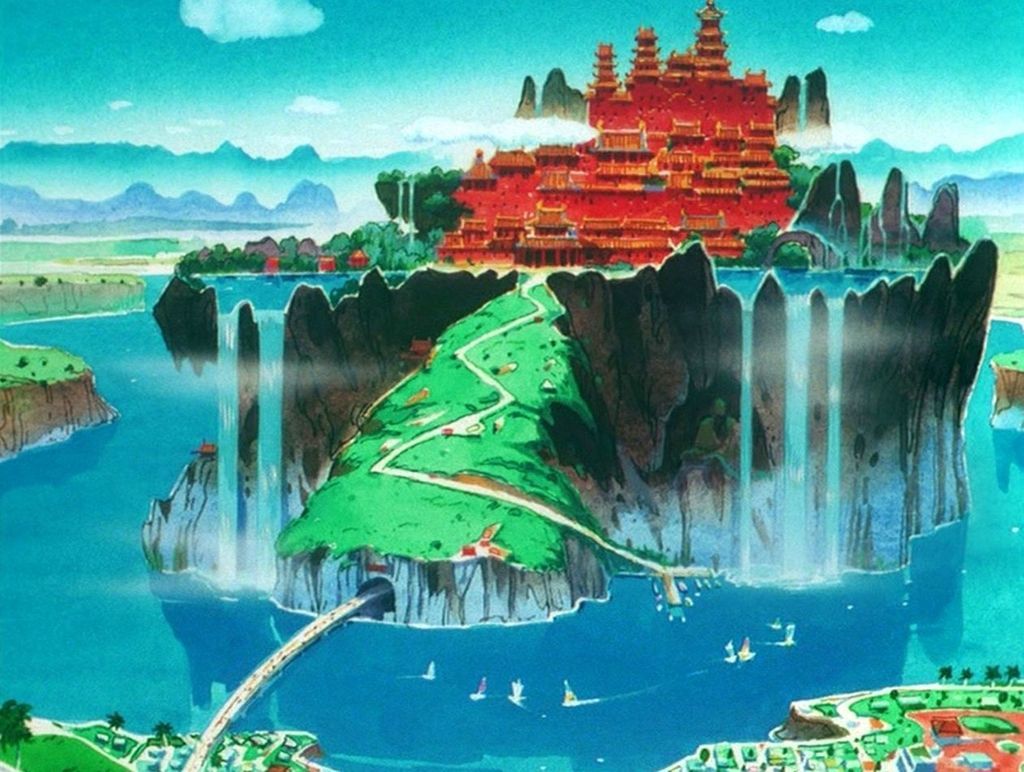

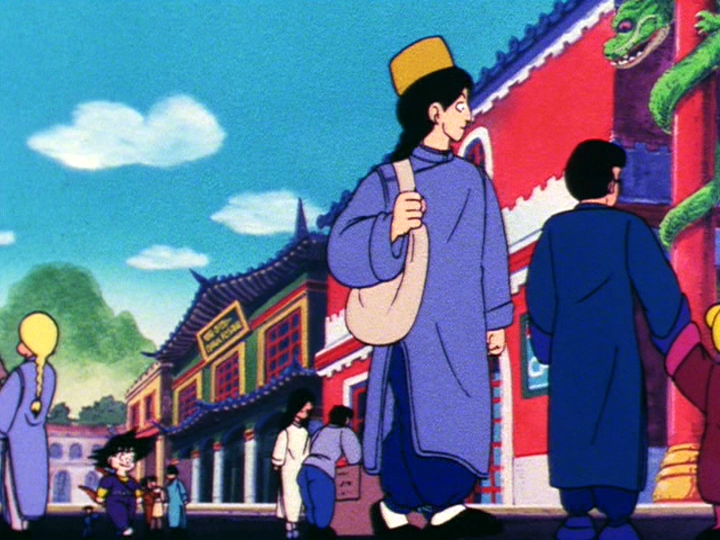

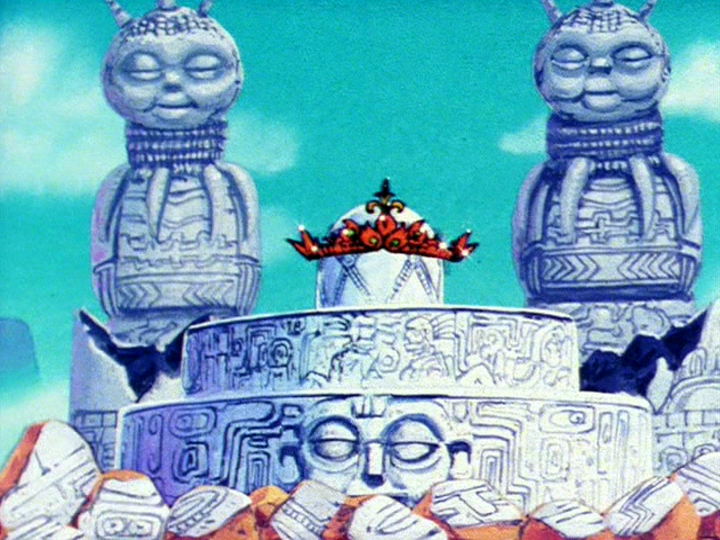

But beyond all that is the ever presence of Wuxia as a whole. Tobias has talked a lot before in interviews about the Wuxia films of Tsui Hark being major influences, and this particularly shows with many of the MKII/Outworld backgrounds which have a very decidedly Zu Warriors-esque flavor to them.

Ki/Chi attacks and various superhuman martial arts techniques are of course also practically mandatory for each character,

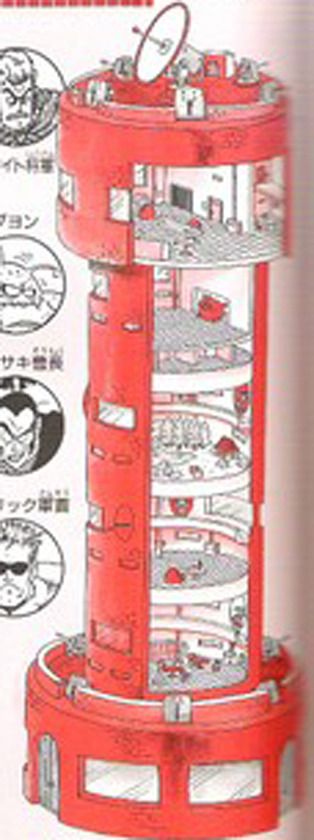

and the entire lore of MK is centered around a series of mystical martial arts tournaments created by deities from Asian religious lore which gives the best martial artists from all over the world a chance to stop hideous demonic creatures from another dimension, including their warlord despot leader, from overrunning our world.

Even the later entries in the series, as they added ever more sci fi and futuristic flourishes (like cyborg ninjas and a post-apocalyptic urban landscape... and its not like Wuxia was any stranger to either of those things well by that point either), would still hang onto the franchise's core Wuxia roots with many newer characters still drawing from popular early 90s New Wave HK Wuxia films.

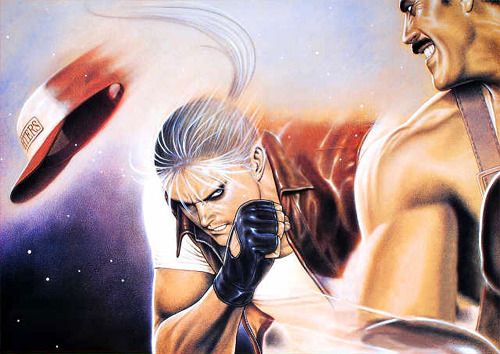

(Mortal Kombat 3's Sindel is largely inspired in her look and fighting techniques by Brigitte Lin's portrayal of Lian Nichang in the classic 1993 Wuxia film The Bride With White Hair, which itself is loosely based on the 1958 Wuxia novel Baifa Monu Zhuan. Lian Nichang has always been a MASSIVELY popular Wuxia character whose unique hair-based fighting techniques have long inspired a great many comic book, manga, and anime characters.)

By the mid-point of the 90s, Wuxia as a whole had achieved a staggering level of widespread popularity, visibility, and recognition on a mass global level it had never achieved in much of its storied long history beforehand. The Japanese were positively devouring it, as were Koreans, Europeans, and even us North Americans.

Not only was the genre spreading its influence across cultural lines like a virus, it had also attained a sort of mystique of “rebellious hipness” among younger people, particularly in its native China due both to the tradition-shirking genre-melding of the post-New Wave stuff as well as the overall themes of the Wulin community as an outsider counter-culture who stand for the power of individual accomplishment over the power of the collective: themes that a Hong Kong still free of its mainland's Communist ideals (for however few remaining dwindling years) was celebrating especially now like never before as the “doomsday clock” countdown to the '97 handover continued unabated.

While that level of deep cultural resonance certainly didn't quite carry over to us clueless Americans, nonetheless a fair deal of the “cool cred” of the New Wave era of Wuxia had managed to rub off on a lot of Western geeks, and the genre (like most of the rest of Hong Kong cinema, and Japanese anime and manga and various underground comics and cult movies, etc.) embedded itself into the early 90s/Gen X grunge American youth culture in its own way.

(If you were a hardcore nerd in the early 90s, chances were you had more than a few of these sitting side by side with your anime tapes.)

And for those more globally/culturally “in the know” about what was going on abroad, the entire Hong Kong cinema landscape of those years was also a fascinating window into what was at once a wild, beautifully surreal and yet poignantly touching and wistful moment in time of a culture basically saying a tearful goodbye to a great deal of creative and artistic freedoms that had defined it for generations, and expressing it (in part at least) with the cinematic equivalent of one great big goofy “bucket list” of crazy, stupid shit to do all at once up on screen.

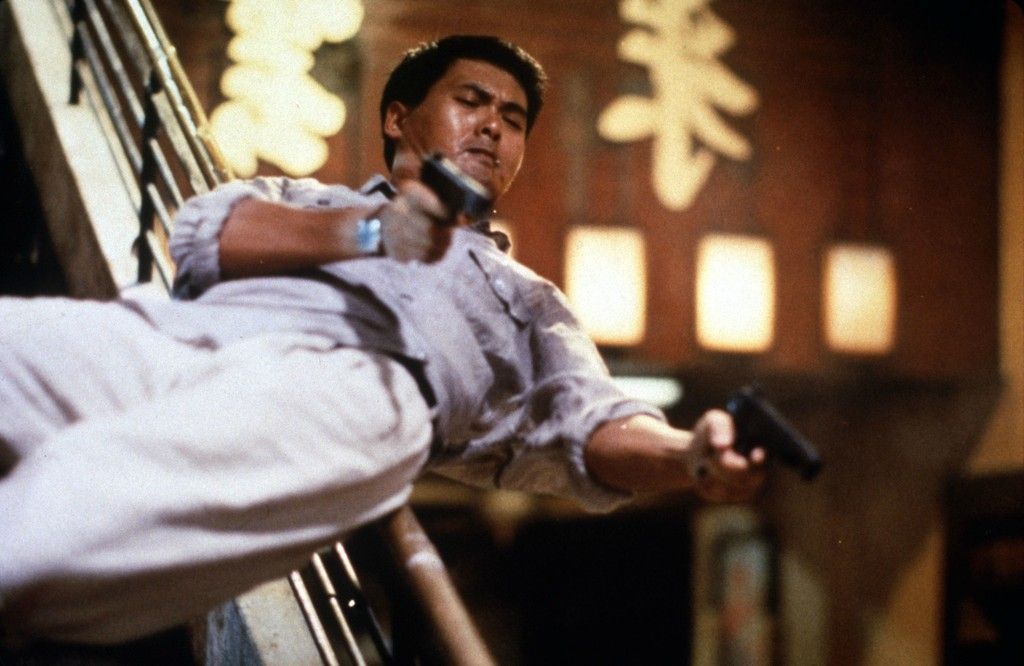

I suppose if your days are (in this case quite literally) numbered, you're gonna go out and you already know it well in advance, this was the way to do it properly: with a gun in each hand blazing, just like Hong Kong's own Chow Yun-Fat.

(“Give the guy a gun and he's Superman, give him two and he's God!”)

My apologies, but I think its written into law somewhere that you can't write this much about classic 80s/90s batshit pre-Handover Hong Kong cinema without at some point referencing Hard Boiled at least once.

Believe it or not though, I still to this day actually have no idea what Japan's excuse was for diving as deep into all this contemporary/genre schizo Wuxia stuff as they did during that period: god only knows why they glom onto even half the shit that they glom onto in general. Giant Ki blasts and tattered martial arts dogi were just an “in” thing during those years I suppose. I'm obviously glad they did though: where would we all be without Street Fighter? Plus y'know, we also wouldn't exactly have had another particular manga/anime series that this whole community is singularly dedicated to obsessing over.

I digress. While Wuxia was more ubiquitous and popular than ever by the mid 90s, it was also - on a surface level at least - all but unrecognizable from its more traditional portrayals in decades past. Other foreign genre influences had thoroughly invaded it from every possible angle: creators had the Wulin community of ancient kung fu legends travel to the modern present, to far off sci fi futures, had them fight zombies, robots, cyborgs, space aliens, genetic clones and science experiments... and it was only getting more out of control and more batshit wacky with each passing year.

(The early 90s ladies and gentlemen.)

What started out as an incredibly refreshing new take on a cobwebbed ancient genre that was at one point in danger of growing somewhat stale had ballooned and spun wildly out of hand into a fad that some would argue (depending on what kind of Wuxia fan you ask) had well overstayed its welcome and hijacked and overtaken the Wuxia genre well past the point of reason.

At the rate that things were going in the early half of the 90s and as the ever-looming Handover whipped up Hong Kong culture into an increasingly nerve-wracked frenzy, sooner or later the genre itself was bound to cave in on itself under the continually crushing weight of all this complete and total madcap insanity.

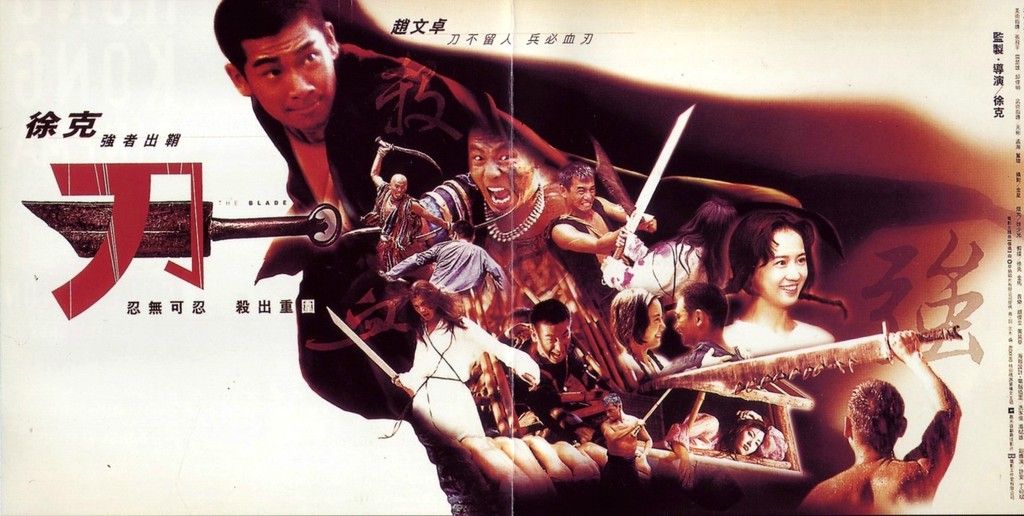

Wuxia in Modern Media Section VI: The Breaking Point and the Swinging of the Pendulum (1993 - 2006)

As much as the early 90s was defined by Wuxia finding more and more new ways to modernize and reinvent itself with different genre influences, it wasn't ALL absurdist horror/sci fi bonkers nonsense. Other, vastly more cerebral and abstract ideas were also tried in an attempt to grow and subvert the genre in extensively creative ways.

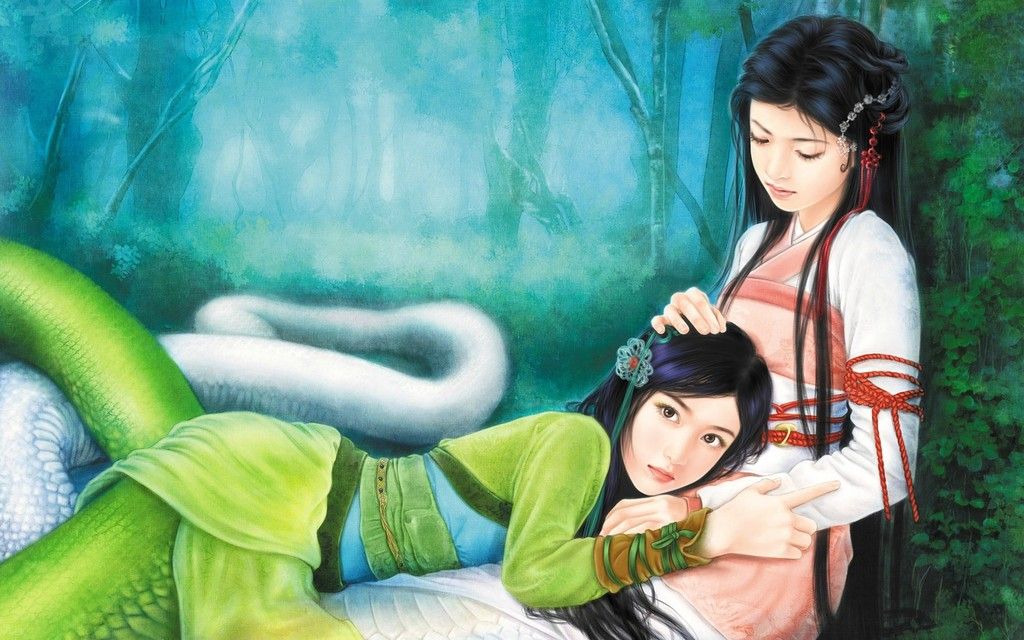

In 1993, a decade after the original Zu Warriors and still well within the white hot heights of the HK New Wave era's creative output and popularity, the style's own godfather (for Wuxia anyway) Tsui Hark would put out one of his most singularly ambitious, challenging, and thematically rich Wuxia films of his entire career: Green Snake.

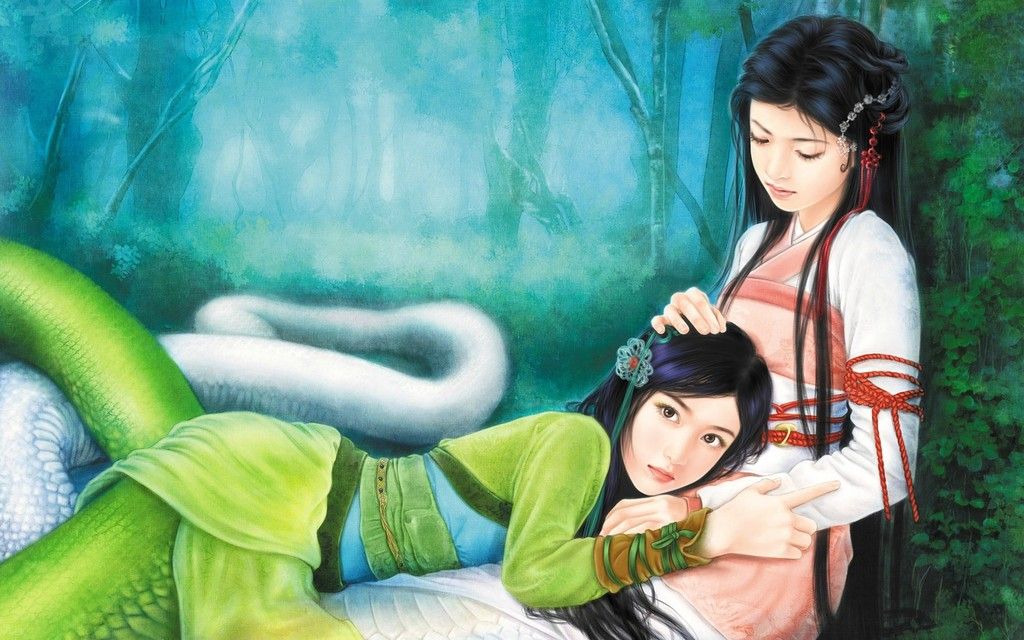

The film is based on the ancient Chinese myth of the Madame White Snake, which is one of the single most oldest Wuxia legends in the genre's entire history (pre-dating written works altogether and originally being passed on orally) and has thus accumulated enough adaptations in enough varieties of media (including fuck knows how many Peking Opera/stage productions) over the years to rival Wuxia standards like Journey to the West and Romance of the Three Kingdoms.

(A 12th century mural depicting a scene from the legend of Madame White Snake.)

In the original legend, a powerful White Snake Demon who has spent many years training in magical Taoist martial arts in order to attain the long lasting life of a Xian lucks into attaining 500 years worth of training within a single day thanks to an unwitting and unseen series of accidents involving an ordinary young boy named Xu Xian and a handful of enchanted immortality pills he had mistaken for rice balls (long story in itself).

Now vastly more powerful and able to transform herself into a beautiful human female form, the White Snake Demon comes to the rescue of a wounded Green Snake Demon, who in sheer gratitude comes to look up to the White Snake Demon as an older sister and begins to train under her. Many years later, the two Snake Sisters are now both able to take on the appearance of beautiful human maidens and travel Jianghu together under the human names of Bai Suzhen (the White Snake) and Xiaoqing (the Green Snake). One day while the two attend a spring festival, Bai Suzhen once more crosses paths with a now fully grown Xu Xian (who has become a scholar), and the two fall in love and get married (with Xu Xian completely unaware of her true demonic nature).

Unbeknownst to Bai Suzhen, a tortoise spirit who had also been training hard to attain Xian-hood and long life had witnessed her fortunate instant power up all those years ago, and grew bitterly jealous. The tortoise spirit eventually grew strong enough to also assume human form and takes on the identity of a Buddhist warrior monk named Fahai. Tracking Bai Suzhen down for revenge, he finds her happily married and running a medicine shop with her new husband.

Fahai vows to destroy her marriage and happiness any way he can and decides to use his sect of Buddhist warrior monks for this goal, knowing that a human and a Snake Demon copulating would be considered a blasphemous offense to the religious fighters. Many intensely supernatural martial arts/Taoist Ki battles break out between the Snake Sisters and Fahai and his monks with poor hapless scholar Xu Xian caught in the middle.

(Fahai vs Bai Suzhen.)

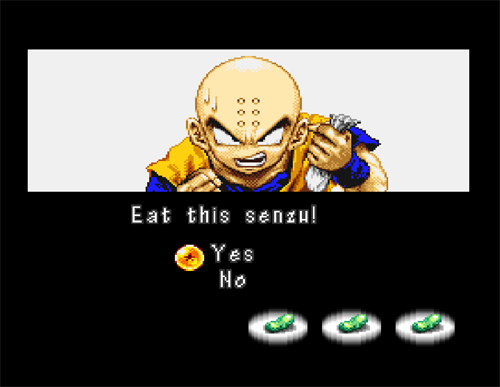

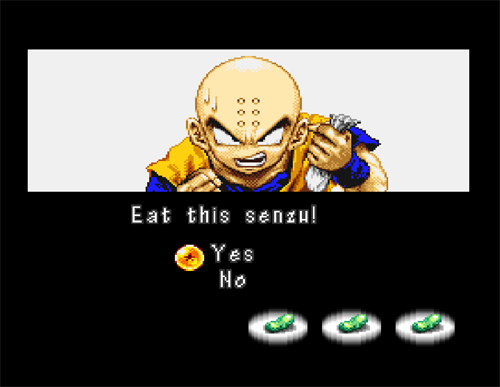

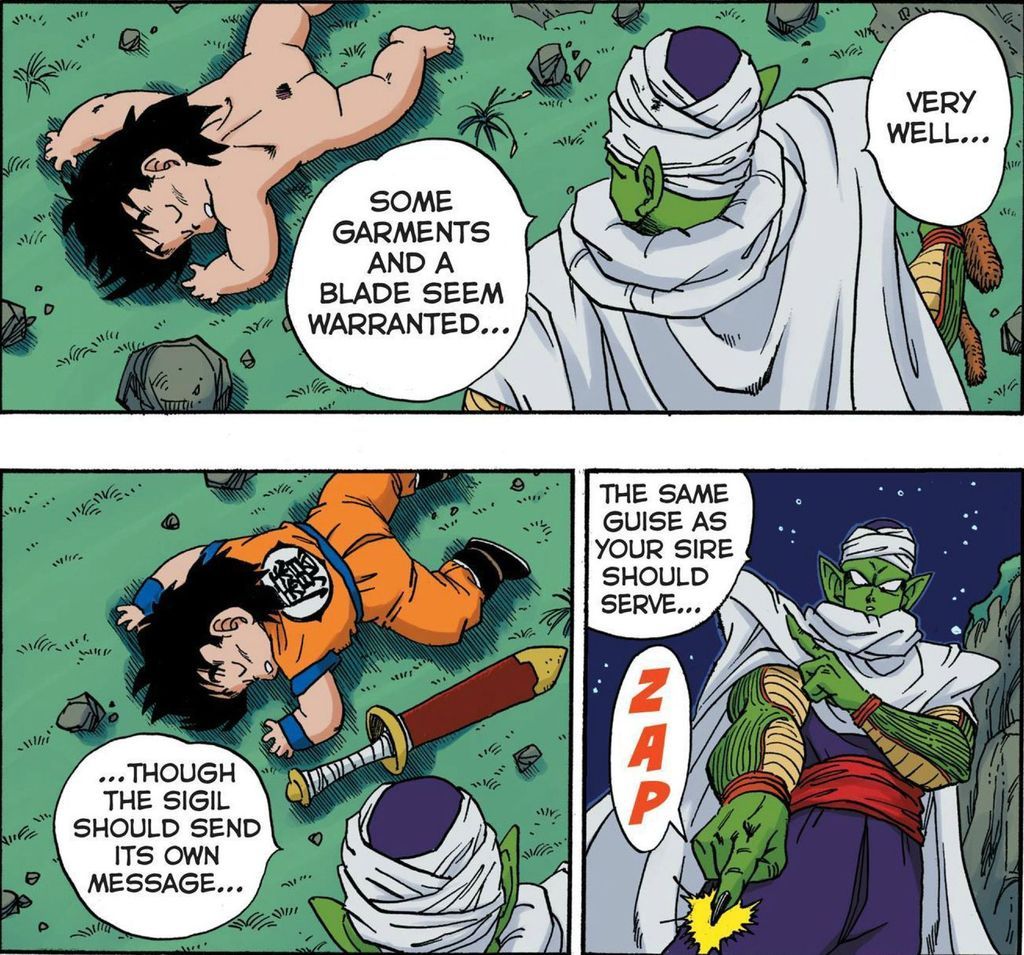

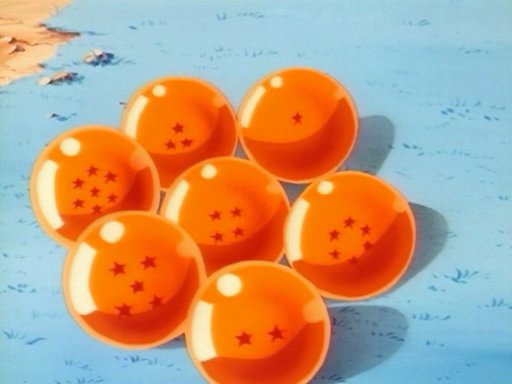

Oh and yes, in case anyone missed it, a key plot point that much of the story's early events hinges on is essentially a magical instant power up for our supernatural martial arts protagonist. From magical food that, apart from granting strength and enhancing a person's Ki, also has the side effect of making the person eating it not feel any hunger for several days afterward.

(Stop me if any of these concepts ring at all the least bit familiar.)

-----------

EDIT (1/4/2016): Didn't notice this till recently, but Derek Padula's awesome "The Dao of Dragon Ball" website has a pretty excellent and spot on rundown of the Taoist concept of "Immortality Pills", which have been a cornerstone staple of Wuxia folklore starting with (as was already noted here) the Legend of Madam White Snake and onward and which are, quite obviously, the basis for Senzu in Dragon Ball. By all means give that a read, as the history behind this is something I definitely should've delved a bit more into here myself.

-----------

Originally played for grim horror in its earliest tellings with Bai Suzhen as a more sinister figure and Fahai and his monks painted in a more heroic light attempting to genuinely save Xu Xian's soul from her wicked clutches, the finer details of the story had evolved and deepened substantially over the centuries into a much more subversive love story about tolerance and the evils of prejudice and meddling in the lives of others who may be different but are otherwise doing no harm to anyone.

This classic Wuxia myth was already IMMENSELY fertile ground for the deeply feminist and politically outspoken Tsui Hark to work with, and in '93 he didn't disappoint in the least bit.

As the title would imply, Green Snake is told more from the perspective of Xiaoqing (the titular Green Snake demon) who in the original legend was a supporting character in the main conflict between Bai Suzhen and Fahai. In Hark's telling, Xiaoqing is put front and center as the POV character and is further fleshed out: always portrayed as the younger, more excitable and impulsive sister next to Bai Suzhen's more mature, collected demeanor, while Bai is getting ready to settle down to a quiet, peaceful existence with Xu Xian, Xiaoqing is torn between living close by her adoptive sister (whom she hero-worships) as a human, or remaining closer to the demon world, unsure of which form she prefers.

Coupled with the still training Xiaoqing's much greater difficulty in maintaining her human guise (and thus keeping her and her sister's secret from an oblivious Xu Xian), and there's a pretty obvious puberty parable going on here of a young girl growing into womanhood and still trying to figure out who she really is, as well as an intriguing examination of closely knit family drifting apart as their lives move in different directions.

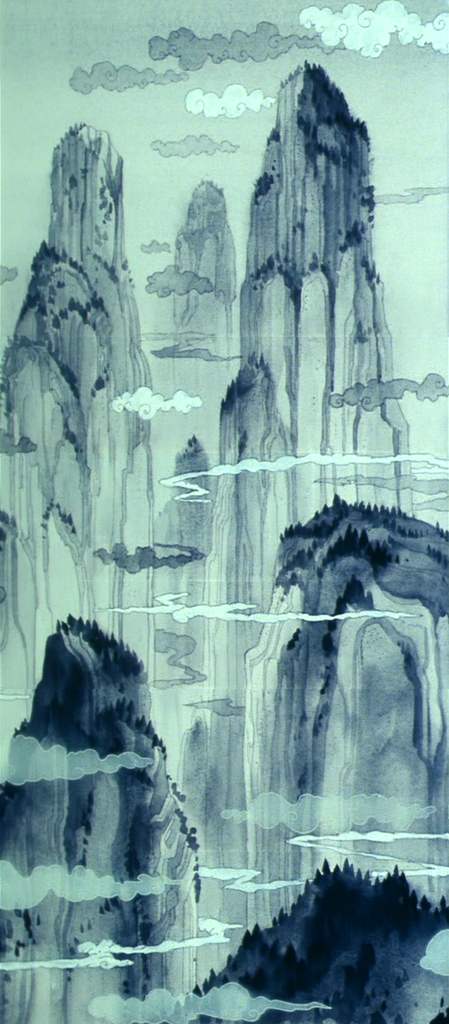

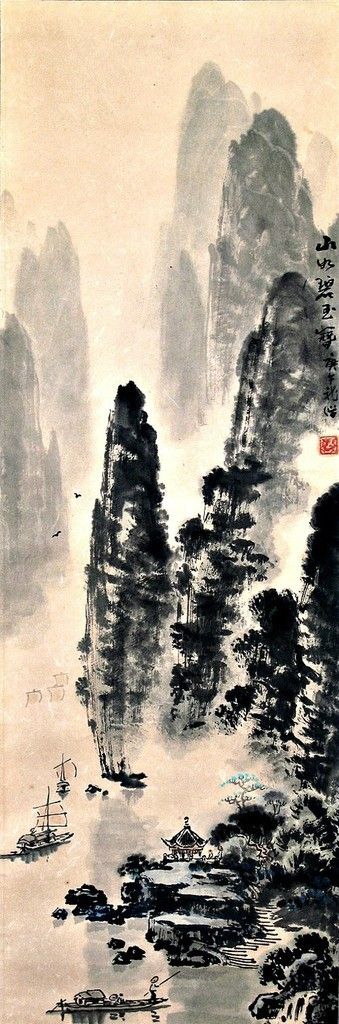

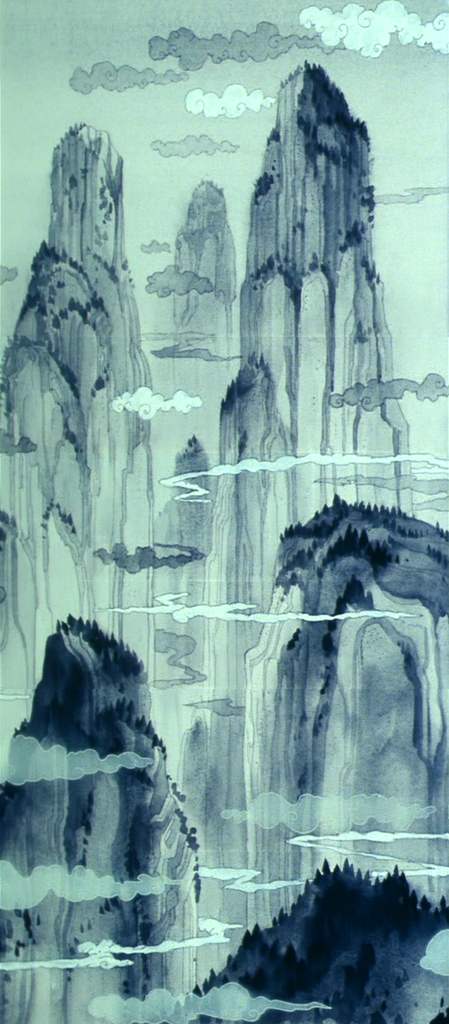

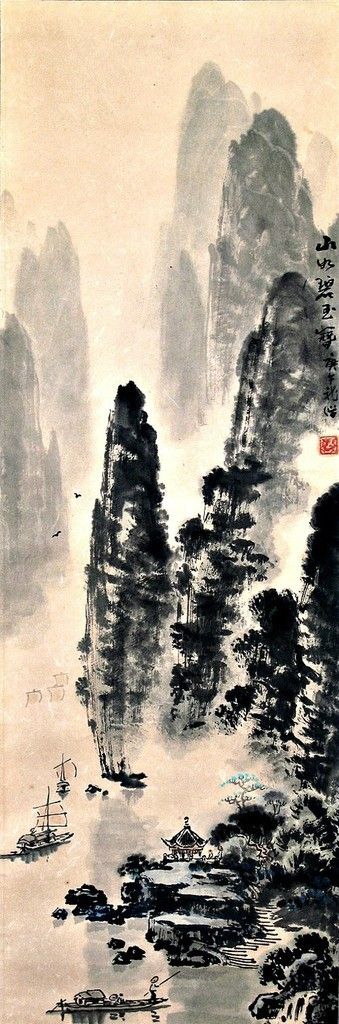

(As with most tellings of the Snake Sisters myth, much of the supernatural displays of martial arts techniques are far less physical and a great deal more heavily axed on the metaphysical and is, as with all of the most fantastical Wuxia martial arts techniques, steeped in Taoist mysticism. On the left: the Snake Sisters are pursued by Fahai in an aerial chase and attempt to lose him by soaring through Jianghu mountain ranges. On the right: Fahai displays his incredible mastery of Kikou by using his purely focused Ki to part the waters of a massive river.)

Also much further fleshed out is Fahai and the motives of the Buddhist warrior monks in general. In this version the monks, with a distinctly deep red motif to much of their robes, clearly are meant to represent Communist China. Yes, Hark managed to add a layer of (at the time) modern day political commentary onto a classic and well worn Wuxia standard, with the plight of the Snake Sisters and Xu Xian clearly intending to represent the artistic, free spirited and individualistically different Hong Kong, and the encroaching monks the looming Handover and the visage of conformist Communist oppression intruding onto innocent lives that didn't ask for any conflict with them. And when they kidnap Xu Xian, their attempts to “cleanse” his spirit of the demon woman's “influence” looks all too suspiciously like the sort of torture found in a reeducation camp.

Fahai as a character is also DRASTICALLY overhauled and given a great deal more depth: his backstory as a jealous tortoise spirit rival of Bai Suzhen taking on a human form is discarded, and the main instigator of the conflict is purely the Buddhist temple's bigotry towards the inter-demon/human marriage with Fahai as one of several temple leaders behind the decision to invade the lives of these people and break up the marriage. However Fahai is made tremendously more sympathetic and three dimensional here and is portrayed as at first as fanatical as the other monks, but ever gradually more conflicted as he continues to slowly see the genuine love in Suzhen and Xu Xian's relationship and begins to recognize the temple's actions and vitriol towards their love as misguided and senselessly hateful.

On top of all that, the movie is just pure eye candy and cinematography porn, with one of the single most strikingly gorgeous and storybook beautiful onscreen portrayals of Jianghu ever put to film, period. Its beyond worth a look purely on that merit alone. And while a much greater emphasis is put on the love story and the various layers of political and sexual subtext, when the supernatural martial arts attacks do start flying, its a lovely, breathtaking sight to behold.

(The Snake Sisters mount an assault on the Buddhist temples by attempting to flood it with their elemental control techniques, as in most tellings of the climax of the Snake Maidens lore. UNLIKE most tellings however, here in Hark's 90s version Fahai attempts to save the temple by singlehandedly hoisting it above the crashing waves with his incredible superhuman strength and ability to fly with his Ki.)

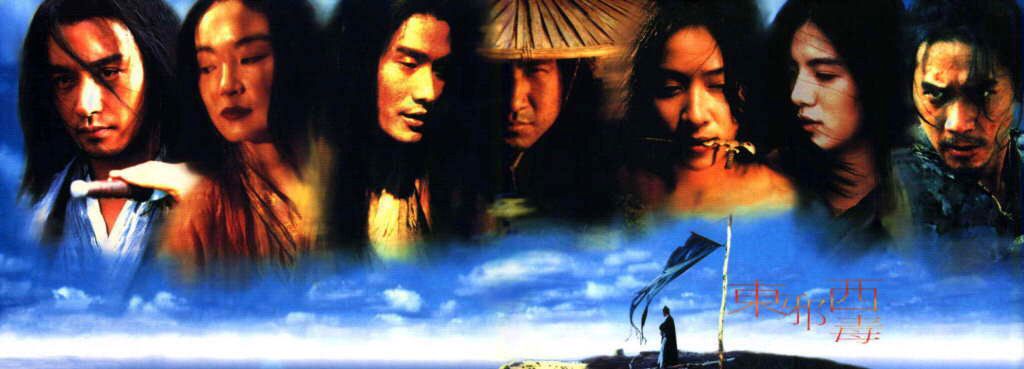

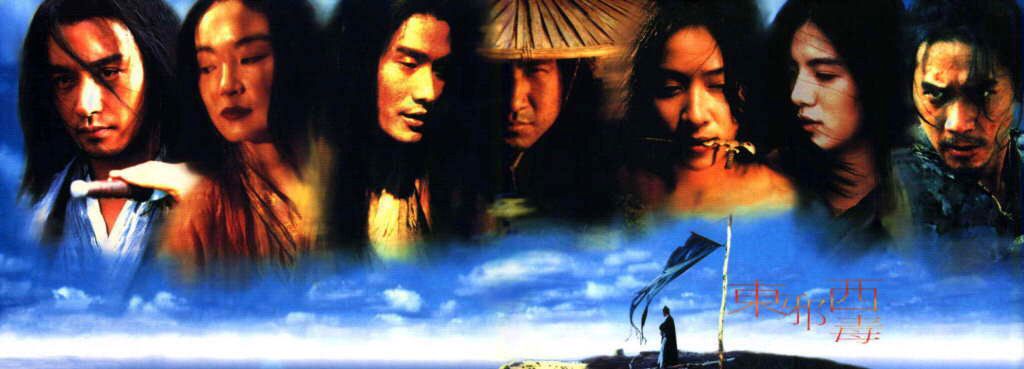

On a similar note, Hong Kong New Wave icon Wong Kar-Wai would also once more return to the genre, this time as both director and as a writer, with the much celebrated 1994 arthouse Wuxia classic, Ashes of Time.

So with YYH we've got a manga/anime series that's set in then-modern 1990s Japan, primarily focusing on Yusuke Urameshi and Kazuma Kuwabara, a pair of rival 14 year old middle school-age rebellious delinquent punks whose very immediate futures seem perfectly poised for a life of petty criminal thuggery and Bosozoku gang membership (and in Yusuke's case, judging by his strongly hinted-at family background in the manga, probably a future even further down the road of life as a Yakuza hood).

The fairly predictable path of youthful ruin for these two boys is completely derailed however when Yusuke is of course run down and killed by a speeding car while uncharacteristically saving the life of a small child within the very first manga chapter/anime episode and is revived as a spirit. Kuwabara not long after has his own latent ESP-like psychic connection with the realm of the dead awakened.

After Yusuke is resurrected by Koenma, son of the mythical Great King Enma (due to him dying before his intended time), he and shortly later Kuwabara are recruited by the Spirit World (afterlife) to be their agents in the Human World (Earth/the living world), investigating and combating incidents involving demons and evil spirits from the Demon World (Hell) running amok.

They're both also joined by Kurama and Hiei, a Fox Demon and Fire Demon respectively, who were both once criminals in the Spirit World and are forced by Koenma (after being apprehended initially by Yusuke) to work alongside Yusuke and Kuwabara as almost a form of spiritual/paranormal “community service”.

Before long however, the series' shifts its focus away from Yusuke's duties as a Spirit World Detective and more towards his, you guessed it, ever growing and evolving supernatural martial arts skills. Upon dying and being resurrected, Yusuke's mind and spirit are awakened to his latent ability to harness and focus his Ki, and he is mandated by Koenma to train this ability in the form of supernatural martial arts by the great master Genkai so as to be a more effective fighter against the demonic hordes he will be facing as a Spirit World Detective.

Among Yusuke's greatest opponents is Toguro, formerly Genkai's martial arts peer and lover, who sold his soul to become a demon so that he will never age or lose his strength as a martial arts master. Toguro becomes obsessed with and fixated on Yusuke's strength and power as a fighter, and his encounters with Yusuke further brings out in the boy his own Youxia-like will and ideals as a fighter to continue to grow and improve for the sake of growing and improving and realizing his own full potential, all the while with Toguro acting as a cautionary tale and tragic reminder of where those warrior's ideals for growth can lead when they completely and utterly consume a fighter to the point of total obsession.

Pretty much most all of Yusuke's major demonic martial arts adversaries throughout the series function in a similar manner to Toguro, acting as dark reflections of Yusuke's own Youxia-like tendencies and showing where they can lead him astray if he doesn't properly apply them and think the ramifications of his actions through clearly.

This is especially apparent in Sensui Shinobu, a once incredibly heroic Spirit World Detective and masterful martial arts warrior who was tragically driven irrevocably and murderously insane by the extreme corruption of the Human World and his own deeply held and unshakable moral and ethical principals as a warrior.

Yu Yu Hakusho is the very essence of early 90s post-modern/post-genre barriers Wuxia personified. You cannot get more specifically dated to that exact moment in time with the genre than this. Coming from Japan as a manga/anime franchise, you've got Bosozoku/delinquent thug elements similar to Osu!! Karate Bu before it, as well as the transplanting of occult/horror and demon/ghost hunting Wuxia elements to modern day Japan ala The Peacock King, all while bringing the afterlife/Bangsian fantasy-centric elements of the genre into the central focus with vast chunks of the series set in the Spirit and Demon Worlds.

(Kuwabara's Rei Ken/Spirit Sword has a dual meaning: being both a Ki-powered sword wielded by a modern day Xia-like character, as well as a Wuxia-ified take on the wooden Bokuto swords often wielded by Bosozoku thugs, whose stereotypical Kamikaze tokko-fuku garb Kuwabara wears as his Xia warrior's dogi/robe of choice. In fact, the first time Kuwabara accidentally created a Spirit Sword from his Ki, it was through using the broken-off piece of an enchanted, mystically powered wooden Bokuto sword.)

Beyond even all that though, Yu Yu Hakusho is a rather intelligent and thoughtful deconstruction of the Youxia archetype by way of transplanting the extremely medieval and archaic nature of its warriors' ideology to a modern day early 1990s setting. Yusuke spends the vast majority of the series working out how to balance his natural, inherent desire to devote his life to growing and blossoming as a supernatural martial arts master with the vastly more liberal and nuanced morality and social responsibilities of modern living, and each of his major rivals and opponents act as generally three dimensional and achingly human examples of where he can go astray in walking the precarious tightrope he spends the series walking.

The incredible success of the post-HK New Wave genre-hybridization and modernizing formula for Wuxia had indeed left its mark on Japanese pop culture through numerous highly popular Seinen and Shonen manga and anime. This would only further continue across ever more mainstream Japanese properties well before the 90s would even reach its back half.

Rumiko Takahashi would dip into the craze a bit with her seminal and hugely influential gender bending martial arts/sex comedy Ranma ½, which sprinkled Wuxia elements of Chinese kung fu mysticism and martial arts rivalries throughout an otherwise farcical “harem” comedy set in modern late 80s/early 90s Tokyo.

[

[

Another popular children's anime franchise to unexpectedly be influenced by the ever-increasing spread of blending Wuxia with other genres by the early 90s was, of all things, the Gundam franchise.

The... ahem... somewhat controversial series Mobile Fighter G Gundam built itself on the premise of essentially being a Wuxia Gundam series, owing to its creator Yasuhiro Imagawa's love of international films, particularly Hong Kong Wuxia and the films of Tsui Hark. Within the series, ruling power over the universe is decided every few years with a martial arts fighting tournament, each world nation being represented by a Gundam battle mech whose pilot (usually an expert martial artist themselves) controls the robot via their own fighting movements, making the Gundam mimic every punch, kick, and various supernatural martial arts Ki techniques that the pilot performs.

Apart from the obvious parallels, the character of Master Asia's Japanese name Toho Fuhai, is actually the Japanese translation of the previously mentioned Smiling Proud Wanderer character Dongfang Bubai, an intentionally direct homage.

By 1993, even that year's annual Super Sentai series would be Wuxia themed: Gosei Sentai Dairanger, which focused on the main team's growing Chinese kung fu/Ki proficiency and training as well as numerous references to creatures and deities of Chinese folklore with its mecha. The villains they faced, the Gorma Tribe, were an ancient martial arts clan who achieved such powerful mastery of their bodies and their Ki that they grew third eyes: this concept is taken directly from a piece of Taoist lore that pops up in Wuxia from time to time and will be further touched on later.

Even the power by which the Dairanger team transforms stems from their ability to harness and control their own Ki, their costumes designed after Chinese kung fu training clothing, and many of their weapons being based on Chinese medieval martial arts weapons common to Wuxia: their quarter staffs in particular suspiciously and likely intentionally resemble Sun Wukong's magical staff.

The continued virus-like spreading of post-HK New Wave Wuxia's influence (and the influence of the various works it had by the early 90s already influenced) hardly stopped at Japanese comics and TV shows though. It of course had a HUGE impact on video games, and is essentially responsible for creating one of the most defining game genre's of the early 90s.

Once more, I believe this one needs little to no introduction.

But for the benefit of those living under a fucking rock for the past 20/25 years now: debuting in arcades in 1991, Street Fighter II is one of the most important flagship franchises of legendary game development studio Capcom and an absolute icon and benchmark of arcade gaming, radically redefining the arcade landscape for what would essentially be its final decade of existence as a cultural entity. It codified and more or less created from wholecloth the vast lion's share of the fundamentals for the modern 2D fighting game as we know it.

The characters and lore behind the Street Fighter series is of course absolutely the byproduct of an Asian popular culture that had for more than a decade before been inundated throughout every pore with modernized and hybridized takes on classic martial arts fantasy fiction.

(The look and aesthetics of many pieces of 70s and 80s Wuxia manhua, manga, and movies, genre blended and otherwise, fueled the look and feel of Street Fighter II's stew of fantasy martial arts mixed with modern sensibilities, as was the well established trend of the time. Here you can clearly see that Vega/Balrog's masked/braided ponytail look was largely taken from the armless warrior Ghost Servant from Chinese Hero. In Chinese Hero, Ghost Servant wears the mask to hide his gruesomely disfigured face, while Vega/Balrog wears his to shield and protect his delicately beautiful and handsome features, which may have been an intentional reference/subversion.)

The main character Ryu is essentially a modern day classical Youxia (mixed heavily with numerous elements of actual real life Japanese Karate masters, namely Mas Oyama), a pure warrior constantly and restlessly wandering the globe in search of new challenges to push his martial arts skills to and beyond their absolute limits. Ryu embodies and lives for nothing but the purity of the fight while striving to maintain the integrity of his honor as a martial arts master: you cannot possibly distill the crux of the Youxia archetype down to its barest essence more than this.

Ryu of course, like any good Wuxia protagonist, is also just as much defined by his rivals as he is his own skills and code of fighters' ethics. His best friend Ken Masters is every bit his American counterpart: brash, energetic, humorous, high spirited, and a bit arrogant, Ken is very much the more down to earth Yin to Ryu's ever stoic Yang, and the careful balance between the pair's deep friendship as lifelong training partners and students under the same master as well as hot blooded rivals in their mastery of their skills is very much at the heart and soul of the series' mythos.

With an international and multi-ethnic cast of warriors each representing a different culture as well as a different fighting style, Street Fighter has over the course of its dense history covered just about close to every possible martial arts character archetype in existence and each of them make up what is essentially within the series' universe a modern day 1980s and 1990s Wulin community: supernaturally powerful martial arts masters who train and exist quietly and on the far fringes of society, making their presence known primarily to test their skills against one another at large gatherings of great masters at major martial arts tournaments, such as those hosted in the series by Sagat and later the criminal empire Shadaloo.

The character Gen for instance, a semi-retired and terminally ill kung fu hitman, is a tribute to virtually every Xian stereotype there is, as well as embodying numerous aspects of countless martial arts assassin characters made especially popular during Shaw Bros. and Golden Harvest's heyday.

Then of course there's the superpowerful psychic martial arts master and drug lord/dictator Vega (or M. Bison if you'd prefer) who takes as much from Japanese folklore and pop culture (namely Hiroshi Aramata's classic apocalyptic occult/onmyodo historical horror epic Teito Monogatari and its iconic villain Yasunori Kato) as he does every possible stripe of Chinese Wuxia warlord characters. Vega/Bison spends much of the series fascinated with Ryu's potential as a fighter and finding ways of exploiting it for his own goals of conquest.

(On the left: Teito Monogatari's Yasunori Kato. On the right: Street Fighter's Vega/M. Bison)

Also on hand is Chun Li, who lends much more of an overtly Chinese flavor to the proceedings (albeit a fairly modernized one, fittingly enough) as well as a more classical “revenge for a slain loved one” storyline that is so indispensable to the martial arts/Wuxia genre.

Also notable are the characters Sagat and and somewhat later on Gouki aka Akuma, a pair of dark analogues to Ryu (similar in many ways to the relationship between Yusuke and Toguro/Sensui in Yu Yu Hakusho) whose obsession with fighting and pushing their skills to their utmost breaking point takes on deeply twisted and corrupt perversions of the Xia's warrior code: though in Sagat's case, not without the possibility for redemption.

Sagat is driven into a mad fit of obsession over his (literally and figuratively) scarring loss to Ryu, which he perceives as unfair, and sells his soul and his ethics as a warrior to the service of Vega/Bison for the chance to even the score and avenge his crushing defeat (and always with deep pangs of regret for the trade off).

Gouki/Akuma meanwhile is the worst possible tragic outcome of a Youxia gone bad: the brother of Ryu and Ken's master Gouken lead astray into mastering corrupt techniques and martial arts teachings for the sake of fueling his own ego and lust for undisputed dominance in the martial arts world, Akuma like Bison sees in Ryu his incredible potential as a fighter and wishes for Ryu to go down the same dark path of mastery as he did under the belief that it is the only true way for Ryu to fully meet his potential and give him (Akuma) the only true challenge left to his skills as a demonic, twisted Youxia fighter.

Part of what's long made Akuma so fascinating as a character is the fine line he generally walks between a semblance of warriors' ethics and outright martial arts villainy. Within the context of the modern day Wulin-esque martial arts world of Street Fighter, Akuma is absolutely unquestionably evil as his yearning to explore and push past his own limits is driven more by vanity and a ruthless need to dominate his challenges (as shown by his casual attitude towards killing and crippling his defeated foes) than by a more compassionate road of using his fights to help teach and train his defeated opponents as much as they teach and train himself.

However, even with all that said, Akuma still abides by SOME semblance of Xia ethics, and will not use his skills and power to victimize completely innocent civilians who do not strive to be fighters at all (unlike Bison, whose corrupting power is a danger to all). Akuma's major flaw that makes him “evil” within the context of a Wuxia story is his total lack of compassion for fighters whose skill is beneath his own. In some stories he could be finagled to be seen as more of an anti-hero: in a martial arts narrative however, his attitude posits him unquestionably on the negative end of the spectrum, a fighter who has clearly lost his way and whose honor has been tainted by his own ego.

Much of the lore of Street Fighter is centered around the concept of Hadou, which is essentially the series' version of Kikou/Ki mastery, and its dark and light incarnations: essentially based off the real life Taoist concept of positive and negative energies in Ki (thus once again, Yin and Yang) with Satsui no Hadou (Surge of Murderous Intent aka Dark Hadou) being a tempting and corrupting influence on powerful fighters - particularly Ryu who spends much of the series struggling against the temptation of giving into Satsui no Hadou in the heat of combat - tapping deep into the energies of Hadou in order to use them to kill or otherwise horribly maim and cripple their opponent beyond the pale... once again tapping into the Wuxia theme of “excessive force is inherently evil and corrupting”.

Also as with much of Wuxia during this time (late 80s/early 90s) across other media, Street Fighter would also add many elements of straight up science fiction into its martial arts storylines, first with Bison's futuristic crime syndicate Shadaloo, then his plans centering on the creation of his “psycho drive” (a massive doomsday device which can vastly increase his psychic powers and supernatural fighting abilities to godlike levels) and various cloned “dolls” (mindless, obedient female servants created in a lab and culled from his own DNA), and even further later on numerous other warriors who are as much government science experiments gone wrong as they are fighters' of Street Fighter's own little Wulin community (characters such as Twelve, Necro, and Seth).

With its focus on martial arts rivalries and warring interpretations of ancient mystical martial arts teachings about powerful Ki mastery and battles raged against an oppressive dictatorial force by a loosely connected sect of powerful and far fringe Wulin martial arts masters, Street Fighter is indisputably a Wuxia tale brought once more to the modern world, as we've well established to be the running theme of the genre throughout the 80s and early 90s. And as with most Wuxia properties that took that track during that time, it paved the way to incredible success and immense, iconic popularity that endures even to this very day.

During its original heyday however, Street Fighter of course would spawn COUNTLESS imitators of its own within the video game world, thus kickstarting the 90s golden era of arcade fighting games. The vast overwhelming majority of these games likewise took their cues as much from various Chinese and Japanese martial arts and Wuxia fiction media, from movies to manhua, manga, anime, etc. as they did Street Fighter itself.

Without question the most successful of all of Street Fighter's fighting game/modern Wuxia progeny was SNK's King of Fighters universe.

Beginning with the two fighting game franchises Fatal Fury and Art of Fighting, those two series would eventually cross over along with numerous other SNK video game properties to create the King of Fighters fighting game franchise.

As with Street Fighter and the rest of Wuxia media during these years, the whole SNK universe of fighting games is a modernized take on numerous Wuxia storytelling tropes and character types retrofitted into a modern setting and often with futuristic elements mixed in for seasoning.

The main storyline for Fatal Fury, Art of Fighting, and King of Fighters as a whole centers around the fictional American city of South Town and the King of Fighters martial arts tournament that is annually held there by corrupt police commissioner and syndicate head Geese Howard, as well as the utterly massive international cast of superpowerful Wulin-like fighters that it attracts from around the globe, particularly the American brothers Terry and Andy Bogard and their close Japanese friend Joe Higashi: a very, VERY similar dynamic in fact to the Chinese brothers/half Russian best friend trio from Little Rascals/Oriental Heroes, and the gritty, hardboiled, crime ridden Chinese slums they inhabited not a million miles removed itself from the mean streets of South Town.

(Central characters Terry Bogard and Wang Xiao Hu even both share a similar “star” motif on most of their street clothing.)

Characters like Art of Fighting's father/son duo Takuma and Ryo Sakazaki are as much staple martial arts/grindhouse/Wuxia character types as they are “heavily inspired homages” (to put it charitably) of Street Fighter's Ryu and other Ansatsuken (Street Fighter's own assassin fighting style practiced by Ryu, Ken, Akuma, et al) characters.

(You may possibly notice some mild similarities.)

Similar to Ryu's Mas Oyama parallels, the fighting style created by the Sakazaki family in the Art of Fighting/King of Fighters series, Kyokugenryu Karate, is also itself derived from Mas Oyama's real life Kyokushin Karate.

(Left: Ryo Sakazaki. Right: Mas Oyama.)

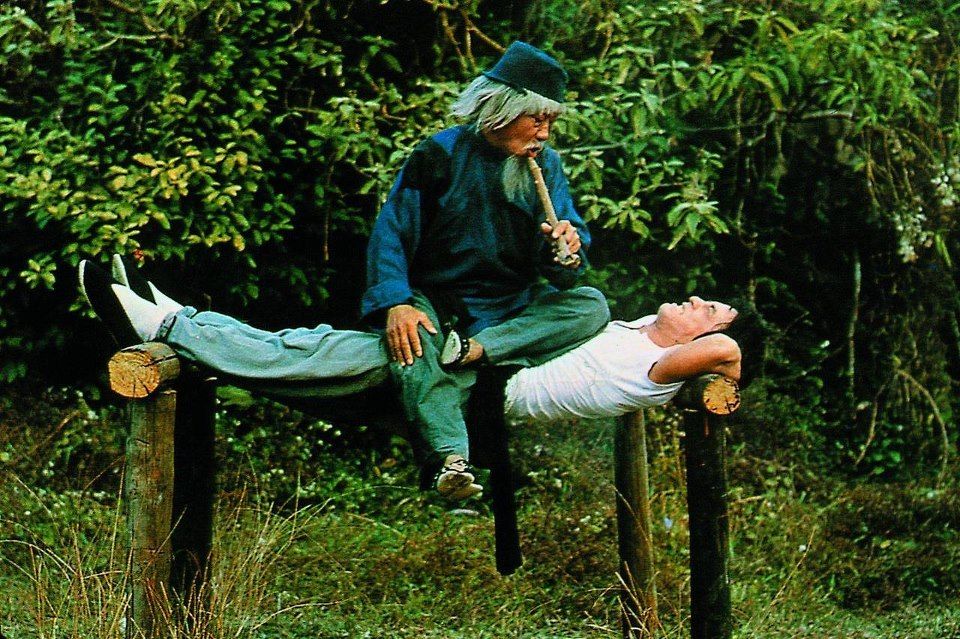

Ryo's father Takuma Sakazaki meanwhile is heavily inspired by Sonny Chiba's character Takuma Tsurugi from the (coincidentally named) “The Street Fighter” Japanese martial arts film series which was a massive and much beloved staple in American grindhouse theaters in the 70s and 80s. Chiba also studied martial arts under Mas Oyama in real life and played him in a number of films.

(A Tale of Two Takumas: Art of Fighting's Sakazaki on the left, Sonny Chiba's grindhouse icon Tsurugi on the right.)

Geese Howard also similarly owes his persona as much to stock crime villains from pulpy grindhouse films and 80s Hollywood action movies as he does from Wuxia, further blending the past with the present as was the martial arts fantasy genre tradition of the day.

Similar to many comic and manga series, the later merged King of Fighters series would be broken up into several “story arcs”, with earlier arcs focusing more on traditional Wuxia mysticism (the “Orochi saga” which centers on the resurrection of a corrupt warrior deity and the ancient martial arts clans charged with ensuring he is never awoken) and later arcs venturing more into sci fi territory (the “NESTS saga” which focuses on a secret underground syndicate who intend to manipulate the King of Fighters tournament for their own corrupt ends).

Further cementing both the Street Fighter and King of Fighters' positions as pieces of early 90s Wuxia media was their Wuxia Manhua adaptations. Street Fighter would get one in 1992 barely a year into its arcade history by none other than legendary Chinese Wuxia Manhua publisher Jademan Comics.

Written and drawn by Xu Jing Chen, the Street Fighter II manhua is gorgeously illustrated and as absolutely early 90s bonkers as genre-blended Wuxia of the era gets, with massive all out free for alls between the incredibly powerful Wulin warriors of the Street Fighter world amidst batshit science fiction subplots centering on evil clone dopplegangers and other such balls to the wall madness.

King of Fighters meanwhile would get a Wuxia manhua much later on in the 90s with Andy Seto's King of Fighters: Zillion followed by numerous sequel series which all ran up through the early to mid 2000s, including a few crossovers with Street Fighter.

Its not at all an exaggeration to say that literally the entire 90s fighting game boom owes a LOT of its existence to Wuxia, particularly the hyper manic crazed genre-busting incarnation that the genre had taken across much of the 80s and early 90s. Very close to almost every major 2D arcade fighting game title released in that time period can be seen, to one extent or another, as essentially a completely off the wall outrageous Hong Kong Wuxia film or manhua in video game form.

By the end of the 80s and dawn of the 90s, Hong Kong cinema as a whole (and Wuxia along with it) had grown MASSIVELY in popularity all across the world. Including even North America. And this time it wouldn't just be the grindhouses and ghettos getting a taste for it (the grindhouse theater industry indeed was fading fast by the late 80s and would be gone entirely by the very early 90s, largely being made obsolete and replaced by the straight to video/VHS industry).

Spurred on largely by the output of John Woo and Tsui Hark, Hong Kong films - particularly Heroic Bloodshed (operatically melodramatic and excessively violent Chinese mob/Triad epics), drama, comedy, and martial arts/Wuxia films - absolutely EXPLODED amongst the so called “Generation X Grunge/Slacker” culture of the time.

Amongst the major Wuxia titles of the time, A Chinese Ghost Story, Hark's wild remake of the King Hu classic Dragon Gate Inn, and the Swordsman/Smiling Proud Wanderer films were particularly huge amongst teens and 20-somethings of the time, many of whom were also (as noted earlier) into and collected anime and manga as well. Due to the vast use of bootleg VHS tape trading used to gain access to both unlicensed anime as well as HK films, a tremendous degree of overlap formed between the two fandoms, intertwining them closely together for a good number of years throughout much of the 90s.

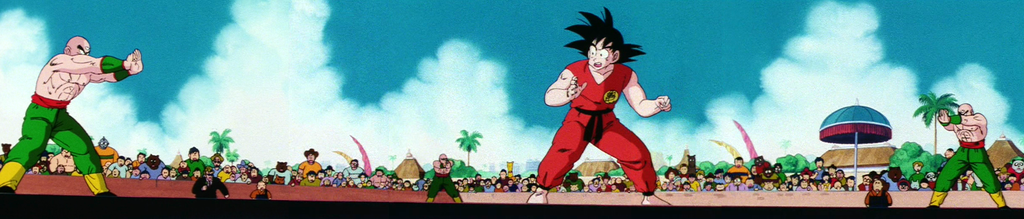

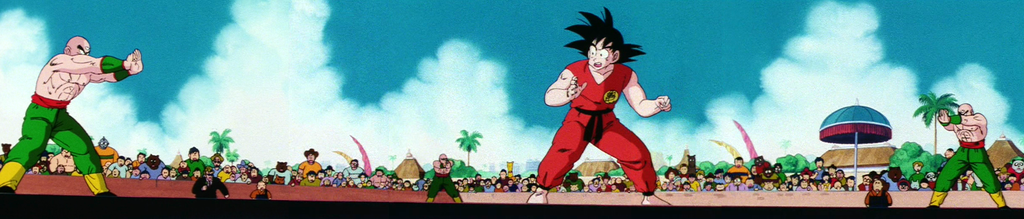

Particularly due to the prevalence of wacky, dementedly over the top Mo Lei Tau humor, a large number of HK action and Wuxia films were seen by many Western fans at the time as essentially live action anime. Coupled with the popularity of similarly themed 2D fighting games and this also fueled into the popularity of titles like Dragon Ball, Yu Yu Hakusho, Hokuto no Ken, and Ranma ½ at the time.

Being Shonen titles aimed at a much younger audience in their native Japan, they tended to glaringly stick out amongst a largely Seinen/Gekiga dominated Western anime and manga landscape (well, maybe less so Hokuto no Ken) of the late 80s/early 90s that otherwise routinely ignored and cared very little for a great deal of Shonen. But the numerous similarities with over-exaggerated and manic energy violent/comedic Hong Kong martial arts/Wuxia films won them a fairly sizable fanbase amongst an older audience who were also plugged into the weird genre-bending sensibilities of the then-still thriving and ubiquitously popular Hong Kong New Wave.

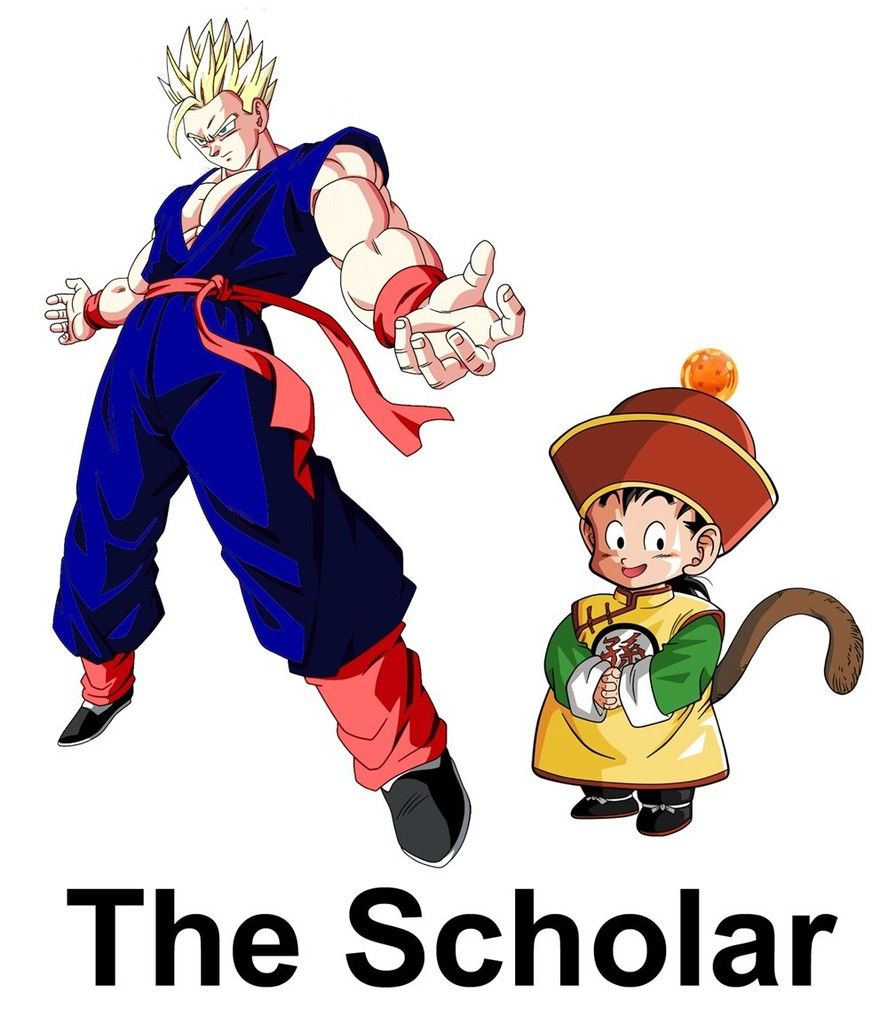

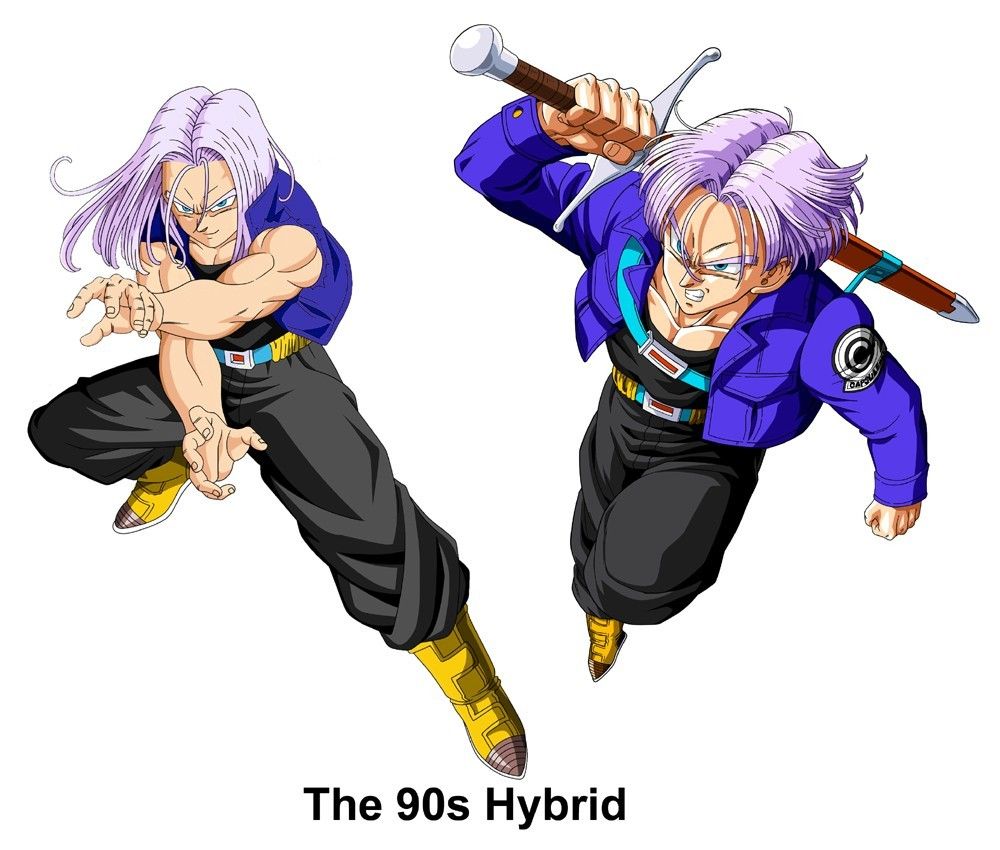

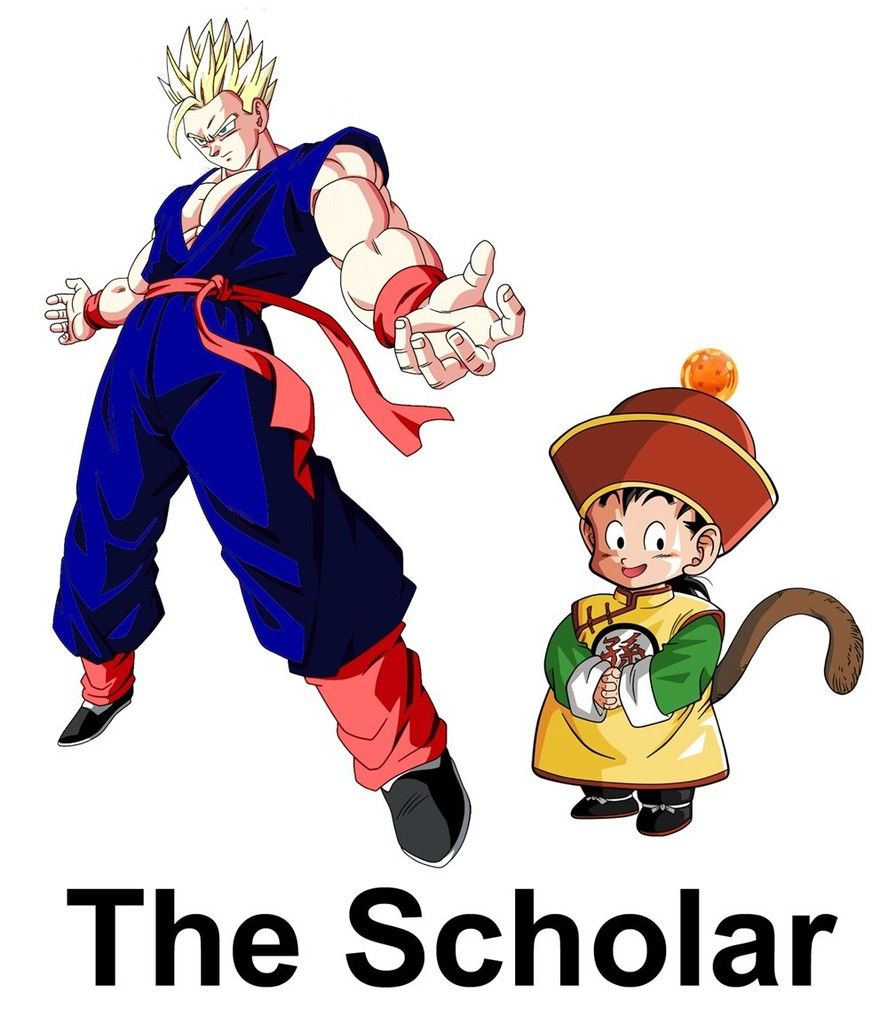

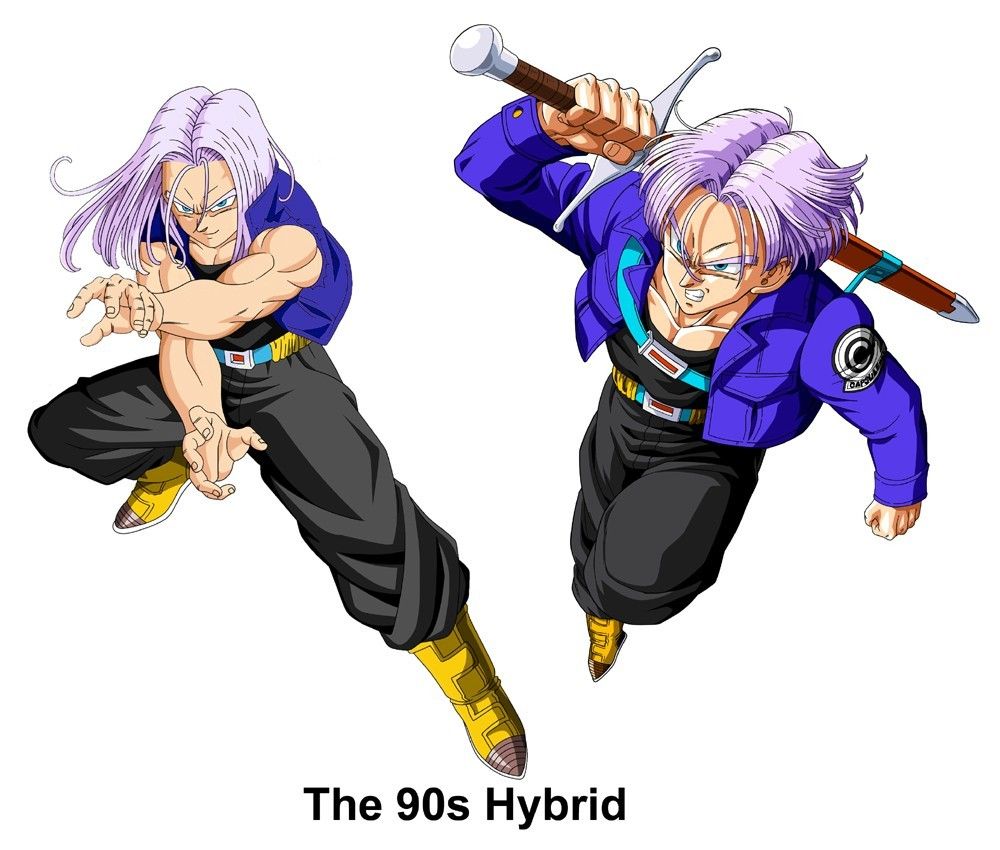

(A very large chunk of late 80s/early 90s Western anime & manga fandom gravitated to the medium on the strength of envelope pushing strictly adult-aimed Seinen titles with a heavy Gekiga visual bent to them, and were typically unmoved by and disinterested in most child-friendly Shonen due to them being seen as largely redundant to a culture that already has long had more than its share of child-aimed animated works for countless years. Certain titles like Ranma, YYH, and DBZ however slipped their way between the cracks of this distinction due to their overt similarities with manically bizarre Hong Kong Wuxia/supernatural martial arts films that were also popular at the time.)

At the same time, while the number of officially licensed Hong Kong films and Japanese anime & manga continued to grow along with bootleg trading of many others that were yet to be licensed, popular Hong Kong Wuxia Manhua publisher Jademan Comics would dive into this growing new North American market during the late 80s and early 90s with officially translated and licensed reprints of many of their own classic Wuxia Manhua, including Ma Wing Shing's seminal Chinese Hero series (published here under the titles of Tales of the Blood Sword and Blood Sword Dynasty), Oriental Heroes, and numerous others, thus further stoking the popularity and visibility of Wuxia among fans at the time.

(An official North American Jademan printing of the 5th chapter of the Wuxia manhua Iron Marshal by Lee Chi Ching, cover dated November 1990.)

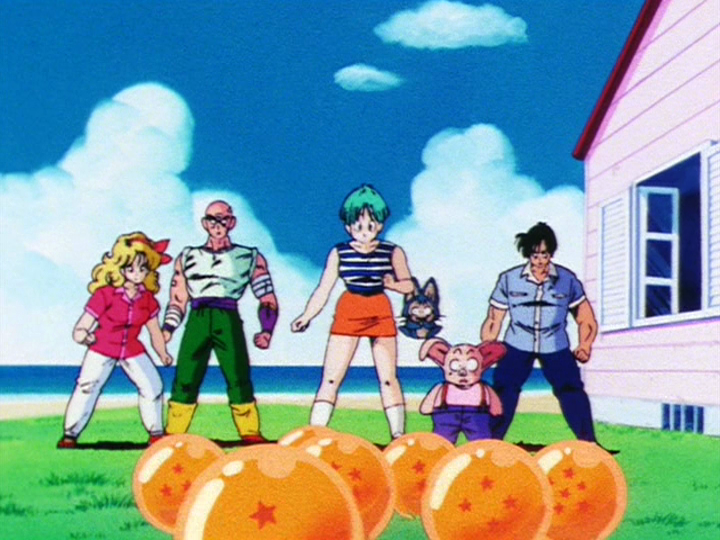

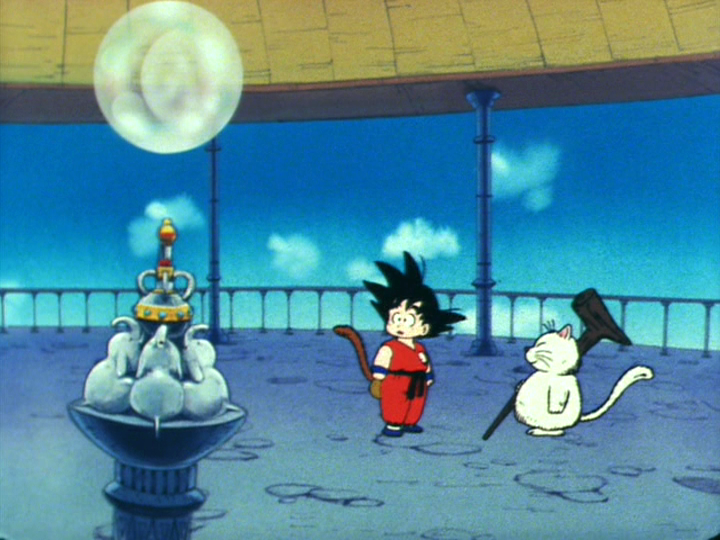

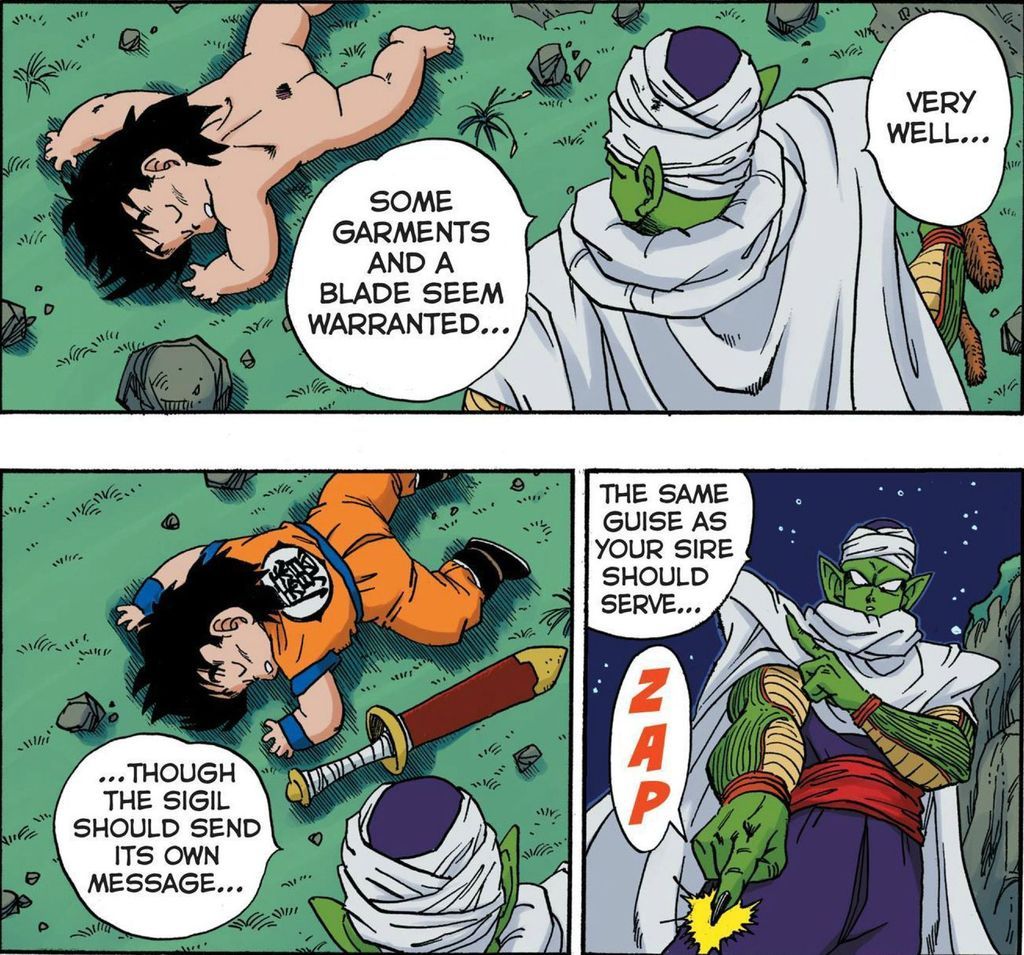

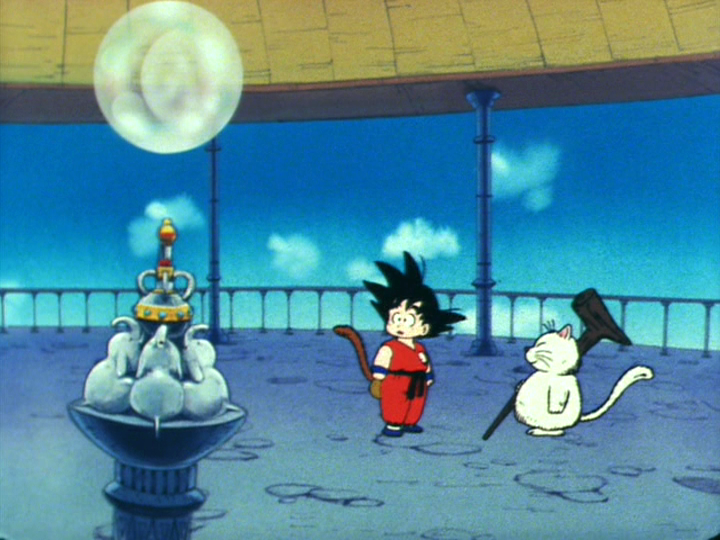

(Some American Jademan issues, as with their Chinese counterparts, also had a section in the back for submitted fan art. You may recognize a certain distinctively hair-styled monkey boy who made frequent appearances in these.)

It cannot possibly be overstated what a VASTLY diametrically different world the Western anime/manga landscape and fandom was in the early-most 90s. While there were definitely still some awkward, super dorky types that one would view as traditionally Otaku, there was also a massive number of flannel and Doc Marten-clad stoners and skater punks that were likewise a huge part of the fanbase as well back then. Their range of interests tended to be a LOT broader than just solely anime and manga, which included all kinds of supremely strange and envelope pushing underground comics and foreign movies... like movies where Chi wielding ancient kung fu mystics go toe to toe with time hopping alien cyborgs from Mars, or what have you.

(Portrait of a typical early 90s American Wuxia/anime fan. As represented here by Floyd from True Romance for... reasons.)

This particular cultural stew of cynical, disaffected punk rock teens latching onto hyper violent martial arts films and whimsical Chinese mysticism along with 2D arcade fighting games with similar themes and motifs spurred on yet another massive and iconic early 90s cultural touchstone amongst the youth of the time, one that was not only made for but also made by EXACTLY the sort of Nirvana-era freaks and weirdos mentioned above.

”Test Your Might”

Oh yeah.