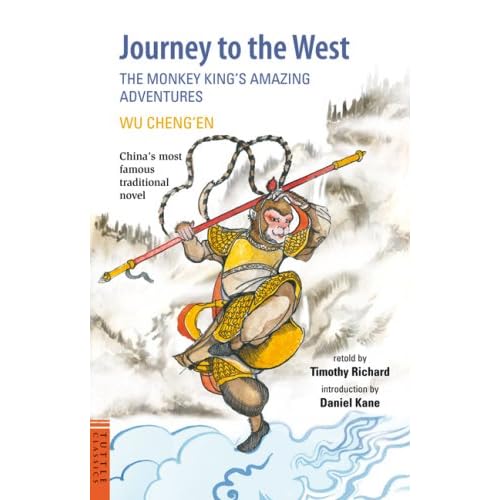

Most fans are well aware of how DB started off as a retelling of the ancient Chinese fantasy novel/allegory Journey to the West, which tells the story of an oddball group of pilgrims travelling from China to India to obtain sacred Buddhist scriptures. Like many of DB’s distinguishing features, this resulted from Toriyama’s laziness: in Daizenshuu 2, he says he came up with the idea of a JttW retelling because he figured that it would be easy to write the series if he had that story as a basis. Longtime fans are all probably familiar with most of the major similarities between the two stories. DB’s Son Goku is based on Sun Wukong, the “Handsome Monkey King” who is more or less the hero of JttW (Son Gokuu is the Japanese reading of Wukong’s name). Oolong is based off of the (literally) pig-headed pilgrim Zhu Bajie, while Yamcha is a more liberal adaptation of the pilgrim Sha Wujing. Bulma is even more loosely based on the (male) Buddhist monk Xuanzang, the lead pilgrim whom the other three are assigned by the gods to project in order to atone for their past sins. The search for the dragonballs itself is a takeoff of the pilgrims’ quest for the sacred scriptures (which unlike the dragonballs are all located in a single place at the end of the trip), while Mt. Frypan and its mini-storyline is adapted from the Fire Mountain incident in JttW. Gyuumao is based on an actual demon bull who figures into the Fire Mountain part of JttW, and the Bashosen is likewise based off the fan in JttW that can supposedly put out Fire Mountain’s flames.

After DB’s first story arc though, JttW pretty much stopped serving as an inspiration for Toriyama. The Tenkaichi Budoukai was inspired by the popularity of similar competition based mini-storylines in Dr. Slump, Muscle Tower comes from the video game Spartan X (itself based on the Bruce Lee film Game of Death), while Piccolo Daimao was inspired by the villains of Dragon Quest, and so forth and so on. But DB’s JttW roots were not entirely forgotten…by the anime staff, at least. More JttW-inspired events popped up periodically in anime filler. Even longtime fans might not recognize these references, and so Mike and I will go over them in this thread. I'll cover the filler character Annin, her furnace, and her mountain home.

THE DB STORY:

At the end of the DB anime there is a five episode long filler story arc that deals with Mt. Frypan again catching fire, trapping Gyuumao along with Chi Chi’s keepsake wedding dress from her mother. In order to save him, Chi Chi and Goku go on a quest to put out the flames. They first think that the Bashosen is the key to extinguishing the blaze, but though they manage to get a new one, using it only makes the flames flare up even higher. Uranai Baba arrives and explains the problem: while the flames that initially engulfed Mt. Frypan at the beginning of the series were caused by a fire spirit that fell from heaven, these new flames are from the Hakke-ro, the Furnace of Eight Trigrams. The Bashosen had originally been a fan used to fan this furnace’s flames, which is why using it to try and put out Mt. Frypan’s flames will only make things worse.

The Furnace of Eight Trigrams is located on the peak of Gogyou-zan, the Mountain of Five Elements, which is situated on the opposite side of the Earth from Mt. Frypan. Looking after the furnace is someone with the title of Taijou Roukun, the “Great Old Exalted One”. Goku and Chi Chi set off to the Mountain of Five Elements to try and convince this person to put out the furnace’s fire. When they reach the top after getting past the mountain’s phantom guardians, the find that Goku’s grampa Gohan has a part-time job working at the furnace. His boss the Taijou Roukun turns out to be a young-looking woman named Annin, who in reality has been looking after the furnace for tens of thousands of years (the name “Annin” is a pun on an’nin doufu, “almond jelly”, a Chinese dessert).

Annin realizes that there must be a hole in the bottom of the furnace, which is why its flames have spread to Mt. Frypan. However, she refuses to put out the flames and fix the hole, because to do so would plunge the world into chaos. The problem is that the smoke generated by the furnace’s flames serve as a gateway to the afterlife. Whenever anyone on Earth dies, their spirit passes through this smoke to go to the other side, and the spirits of those long dead also use this smoke to return to Earth to visit their families on certain holidays. If the fire were put out, the smoke would disappear, leaving all these spirits trapped on Earth unable to pass on. This would turn the world into a living hell, and what’s worse, once the fire is put out it takes at least 2,000 years to start it back up again. Fortunately, when Annin sees that Goku has the Bashosen, she thinks of a way to fix the hole without putting out the fire. While she holds the furnace up, Goku swings the fan to temporarily part the flames, creating a safe passage to the bottom of the furnace. Goku is then to go down there, plug up the hole (by an astounding coincidence, Goku and Chi Chi already happened to find the rare materials necessary to fix it up earlier when they were searching for the Bashosen), and then jump back out again before the flames remerge. As you might expect, everything goes according to plan and the day is saved.

THE JOURNEY TO THE WEST STORY:

So what does any of this have to do with Journey to the West? Well, at the beginning of the novel, long before the titular journey gets underway, there’s a lengthy section dealing with the birth of Sun Wukong and the life he led before joining Xuanzang’s pilgrimage. After being born spontaneously from a rock, the monkey Sun Wukong gains great power studying under Taoist mystics. He uses this power to cause all sorts of havoc, until the Jade Emperor, ruler of Heaven, gives him an official rank in Heaven in hopes that this would settle him down. On the contrary though, when Sun Wukong learns that in Heaven he is little more than a glorified stable boy, he starts causing trouble again, going to war with all of Heaven’s armies. After great effort, Sun Wukong is finally captured by the god Erlang Shen and taken to Heaven for punishment. To the gods’ befuddlement though, they are unable to harm him in any way. Laozi, the deified founder of Taoism, steps forward and explains that because Wukong has ate and drank various divine foods, including Laozi’s own immortality elixir, his body is now as hard as a diamond.

If you’re still wondering how this all ties into the DB filler arc, here we go: while “Laozi” (or its variant spellings) is the name Taoism’s founder is most commonly known by, it is just an honorific title. His real name is supposed to have been “Li Er”, and in addition to “Laozi” he has various other honorary names and titles, including “Taishang Laojun”, meaning “Great Old Exalted One”, which in Japanese is read as…”Taijou Roukun”. It’s under the name Taishang Laojun that Laozi appears in JttW (though some English translations just call him “Laozi” or its variants since that’s what most Westerners know him as). After getting hold of Wukong, Laozi/Taishang Laojun puts him into his Furnace of Eight Trigrams, an alchemical furnace that will reduce Wukong’s body to ashes and extract all the immortality elixir that he drank, allowing Laozi to reclaim it. But Wukong, crafty as ever, manages to survive the 49-day alchemical process (I’ll explain how later) and escape from Laozi.

By this point, the gods in Heaven are desperate, and bring in their last and best hope: Buddha. The Buddha confronts Wukong and makes a bet. If Wukong can jump off of the palm of the Buddha’s right hand, then he will receive the Jade Emperor’s throne, but if he fails he must do penance down in the mortal world. Wukong eagerly takes up the challenge and uses his superhuman jumping skills to leap as high off the Buddha’s palm as he can. He comes to five great pillars above the clouds, where he writes his name and pees to prove that he had been there. He jumps back down again and tries to claim victory, but the Buddha reveals that the five pillars Wukong saw where just the five fingers of the Buddha’s right hand; his hand even has the writing and monkey urine to prove it. Wukong thinks that this must be some sort of trick, but before he can do much about it, Buddha throws him back down to the mortal world. Buddha then transforms his fingers into the five classical Chinese elements (metal, wood, water, fire, and earth), which combine together into a mountain that pins Wukong down, and to finish the job he seals Wukong to the spot by engraving the mountain with the mantra ”Om Mani Padme Hum”. Wukong is stuck under this aptly named “Mountain of Five Elements” for centuries until he is freed to accompany Xuanzang on his pilgrimage to atone for his misdeeds.

So there you have it: this is where the DB filler arc’s Taijou Roukun (Taishang Laojun), Furnace of Eight Trigrams, and Mountain of Five Elements come from. The anime staff really just took these names and used them for completely different things in a completely different story, but this isn’t really that much different an approach than the one Toriyama took during DB’s first story arc.

THE EIGHT TRIGRAMS AND FIVE ELEMENTS:

You might still be wondering just what the heck the “eight trigrams” are, and what they have to do with alchemical furnaces. “Eight trigrams” is the common English translation for the Ba Gua (八卦, hakke in Japanese), a set of eight Taoist symbols that represent the “fundamental principles of reality”. Super-literally the phrase means something more like “eight divination symbols”, but they’re commonly called “trigrams” in English because each one consists of three lines. Each line can be either broken or unbroken, and so the eight symbols consist of every possible combination of broken or unbroken lines: ☰ ☱ ☲ ☳ ☴ ☵ ☶ ☷. These symbols have been used for many different purposes, from fortune-telling to geography. The I Ching is a famous Chinese book of divination that analyzes the 64 possible pairs of the eight trigrams. Each of the eight trigrams correspond to (among other things) an aspect of nature: sky (☰), marsh (☱), fire (☲), thunder (☳), wind (☴), water (☵), mountain (☶), earth (☷). In DB, when Uranai Baba explains about the Furnace of Eight Trigrams, a diagram showing the kanji for each of these eight elements is shown.

While originally Taoism was more of a purely philosophical religion, concerned with how to best live your life in accordance with nature, over time Taoists came to be interested in using alchemy to refine their bodies and achieve immortality. As a result, the figure of Laozi (now deified) came to be pictured as a divine alchemist who brews the elixir of immortality in his furnace. And what better to adorn the Taoist founder’s alchemical furnace than those all-important Taoist symbols, the eight trigrams? In this way, the figure of the deified Laozi, Taishang Laojun, was created, and it’s in this form that he appears in Journey to the West. There’s no evidence that the historical Laozi was interested in alchemy or literal earthly immortality, but then it’s also debatable whether there ever was a historical Laozi at all.

Anyway, this brings up the question of how Sun Wukong managed to survive in Laozi’s Furnace of Eight Trigrams. In the story, Laozi’s furnace consists of eight compartments representing the eight trigrams, and as I explained before, each of the eight trigrams corresponds to a particular aspect of nature. These aspects interact according to complex rules of Taoist cosmology, and Wukong uses this to his advantage. Once inside the furnace, he crawls into the compartment corresponding to wind (☴), because wind blows out fire. This Pokemon-like strategy allows Wukong to escape the flames, but the wind from his compartment blew up smoke from the fire which permanently reddens his eyes.

You might also be curious about what exactly the “five elements” which the Buddha uses to imprison Wukong are. “Five elements” is a common English translation of ”Wu Xing” (五行, Gogyou in Japanese), an ancient Chinese theory of natural philosophy which holds that all things come about through the mutual interaction of five basic components: wood, fire, earth, metal, and water. 五 means “five” and 行 refers to movement (in Japanese it’s used to write the word for “go”, for instance), so “five movements” is used as a more literal translation than “five elements” (other translations include five phases, steps, or stages). This theory has been compared to the classical Greek elements (fire, earth, water, and air; sometimes aether as well), though how apt that comparison is seems to be a matter of debate. Here’s an interesting discussion from the discussion page for Wikipedia’s Wu Xing article:

To which someone else responds:As the article itself says (and in light of the "Wu zhong liu xing zhi qi" discussion above) "Five Phases" is truer to the meaning of Wu Xing ("five walks," "five movements"). Wood, Fire, Earth, Metal, and Water represent energetic states that transform over time. The erroneous but now-entrenched mistranslation, "Five Elements," originated with Jesuit missionaries who accompanied Dutch mariners to China. Steeped in a classical Greek and Roman framework of thought, the knowledge-loving Jesuits presumed that the concept of Wu Xing was similar to the idea of the Greek elements——fire, water, earth, and air——which were formerly thought to be the elemental building blocks of all things. Wu Xing is not the same idea at all. Wood, Fire, Metal, and Water correspond respectively with spring/growth, summer/maturity, autumn/decline, and winter/death/birth, with Earth as the balancing and transforming center. Wood is also wind, Fire is heat, Earth is humidity, Metal is dryness, Water is cold. There are other resonant correspondences to colors, odors, flavors, and in medicine, to body parts and functions. Those resonances are complex and extend throughout the macro- and microcosms. But they are definitely not "elemental" in the Greek sense. Throughout Wikipedia, all references to the Chinese "Five Elements" should be changed to "Five Phases," with redirects where necessary. (I have not edited this article, and leave this work for others.)

(Maybe it’s just my inner skeptic, but I think both of these people sound like crackpots. Still, hopefully this gives you some insight into how people conceive of the Wu Xing.)What's with the "hence the preferred term Five Phases"? Preferred according to whom? I completely disagree that Elements should be banished. I am a Five Element acupuncturist. I have searched for a better term than Elements, but there isn't one. And it's certainly not "phase." A phase is like a station or season one passes through. Hence, as you're going through one phase, you're not in any other phases. This implies that the Elements exist separately from one another. They don't. They are all part of one whole. Despite the fact that Fire dominates Summer, the other four Elements are always present. Moreover, the Elements themselves are also substances. Water is water! Earth is earth! Wood in the human body is tendons/sinews. Earth is muscle. Water is also bone. Elements is a good term. Like the chemical elements, they can exist in a number of different states (spirits in the heavens, matter on earth), and like the chemical elements, they combine in an infinite array of ways to form the myriad things that fill the universe. I agree that "element" is not perfect, but it's better than "phase."

ALTERNATE NAMES:

Finally, I’ll wrap up with notes on some alternate translations for stuff, just for good measure. Anthony Yu’s complete translation of Journey to the West calls Laozi’s furnace the “Brazier of Eight Trigrams”, and Wukong’s mountain prison the “Mountain of Five Phases” (“five phases” being an alternation translation for Wu Xing/Gogyou, as explained above). On the DB side of things, the subtitles for Funi’s DB DVDs call the mountain simply “Mt. Gogyo” and the furnace the “Eightfold Furnace” (in the dub it is simply the “Magic Furnace” and the mountain is “Mount Five Element” or, oddly, the “Dark World”). For some reason the subtitles substitute “Pyre Keeper” for “Taijou Roukun”. As mentioned before, Taijou Roukun more or less translates to “Great Old Exalted One”. But it is a title for Laozi, and Laozi keeps a furnace, and a furnace is kind of like a pyre, so…whatever. For Kanzentai, I’ve gone with “Mountain of Five Elements” and “Furnace of Eight Divinations”, and have usually left Taijou Roukun un-translated, though exactly how I break the word up varies (I also translated it as “ancient and revered individual” for the episode guide).

Aaa~~aaand that about wraps it up for Annin and her wacky furnace and mountain combo set. Mike has some stuff on Ginkaku and Kinkaku from DB episode 79 that he should post up soon.