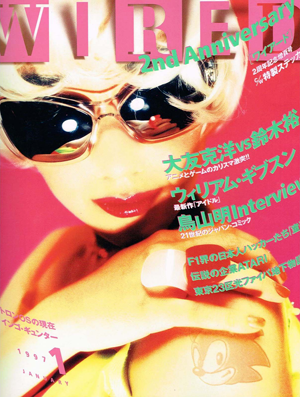

WIRED Japan 1997 #1: “Issue 3.01” (21 November 1996)

Akira Toriyama Interview

Thus Spake Dr. Slump

WIRED Exclusive!!

interview+words Masanori Nakamura (WIRED)

illustration Akira Toriyama

Ever since the shocking debut of Dr. Slump, the cartoonist Akira Toriyama has shouldered the Jump brand’s leading attractions. Wired has succeeded in gaining access to the master himself, who has had an extremely small amount of media exposure. From digital comics to manga production techniques, and even the famous “Jump System”, we’ll introduce everything about the “Toriyama school of cartoon thought”, revealed for the first time.

Wired: It seems that the move to digital has begun, with even things like comics being put on CD-ROM. Do you think that digital comics will continue to increase in number from now on?

Toriyama: I think they’ll probably keep increasing gradually. If we’re just talking about CD-ROMs, then ultimately it’s almost entirely the same work as reading comics [in print], since you’re entirely free to do things like go back [in the book]. CD-ROMs might even be better in that they don’t get discarded and thrown away like paper comics. However, in spite of saying that, it really is difficult to discount the sensation of paper. I’m entirely of the mindset that when it comes to books, they’ve got to be paper.

Wired: Even if the day comes when digital is the primary medium for comics…?

Toriyama: Well, that in itself is obviously not a problem, as far as I’m concerned as an individual. People who prefer CD-ROMs will go with CD-ROMs, and people who want to buy [print] books will buy them in print; that’s fine, don’t you think? But once, for instance, voiceovers and such get put into it, then I think it would probably no longer be in the same field as comics. After all, in the case of paper comics, there’s the fact that everyone can read while imagining voices for the characters as it suits them. Likewise for sound-effects. And also, oddly enough, because with comics, there’s the aspect of how you’re actually looking at an entire spread of two pages. You’re aware of how, “this panel is bigger than this one, so it’s a more powerful scene”. So, if they all come out with the same size panels, it might feel a bit “off”. All I’m saying myself is that I think “reading comics on a screen” might be best.1

Wired: You also work on the character designs for Dragon Quest; do you like computer games, then?

Toriyama: No, I’ve actually hardly played them at all. In terms of character design as well, to be frank, at the very beginning I was drawing them without half a clue what I was doing.

■ A manuscript, after I’ve finished drawing it, is just pictures

Wired: In recent years, in both sci-fi movies and fiction, I feel that there have come to be a lot of near-future settings, to say that they’re very much within the realm of possibility. Is the same trend present in comics, as well?

Toriyama: It’s also like that in comics. They put emphasis on reality rather than imagination. As you say, if it’s not something that, to a certain extent, readers can understand within the limits of their imagination — like the near future — then it won’t be popular. There is the received wisdom that “you won’t get anywhere [with readers]” if you do hard SF, or rather, “if you draw a story about life-forms with a completely alien culture on a completely different planet”.

Wired: So [you do] things that can be interpreted within the setting of human society….

Toriyama: That’s right. So back when I started Dr. Slump, it was a time when there were still higher-ups at Shueisha who would complain, “Why do the animals talk?” (laughs) I don’t think something like that would occur anymore, though.

Wired: Dragon Ball is apparently very popular even overseas; how does it feel, finding success abroad?

Toriyama: Hmmm, well, I am happy, but I can’t really fathom it. (laughs) It’s not like I drew it with other countries in mind, or anything. It feels like it’s someone else’s business.

Wired: Why do you think that Japanese comics, not limited to Dragon Ball, have been rated highly [in other countries]?

Toriyama: Let me see here…. For instance, in places like America, comics tend to be reading material for children, and have an extremely simple story, so that when [readers] become adults, it’s not something they would read anymore. Or rather, they all start watching movies, instead. In that sense, I think there’s probably also an aspect of how people who would be making movies if they were in America draw comics in Japan, because in Japan, you can’t eat [on the money from] doing movies.

Wired: Since they’re in a situation where they don’t have a place to channel their talents, they inevitably gravitate towards comics.

Toriyama: I think that’s definitely the case. After all, if a cartoonist’s work is successful, he’ll make money, right? So I suppose it’s easy for talent to accumulate there, no matter what. At any rate, part of the charm is that you can do everything yourself, from the story to the art. It’s like making a movie all by yourself…. there’s no way you’ll have a difference of opinion, after all.

Wired: In drawing comics, what is your ratio of visual information to textual information?

Toriyama: Really, as far as information is concerned, the visual side is bigger.

Wired: With what stance do you view words?

Toriyama: At any rate, I don’t waste much time blathering on about useless things. As a rule, you can understand the content to a certain extent with just the pictures, and words are nothing more than a supplement to them. I had that drilled into me by my first editor, I guess you could say…. If you’re going to come out and say something, then make it something that will strengthen the characterization even further, is what I mean.

Wired: You have to choose carefully.

Toriyama: Yes, that’s right. Instead of blathering on and on, how are you going to keep it concise?

Wired: Toriyama-san, whether it be Dragon Ball or Dr. Slump, I think your works have a large number of really “stand-out” characters that are able to coexist.

Toriyama: That might be something that was fostered in me through doing advertising design. I think that the very fact that I had to draw all these different things for supermarkets and big retailers, looking back on it now, came in handy.

Wired: Without realizing it, you were learning the basics….

Toriyama: Right. Also, keeping a deadline was also something that was fostered in me at that company. (laughs)

Wired: Do you properly store your manuscripts after you draw them?

Toriyama: After I’ve finished drawing them, I feel like they’re just pictures. (laughs) A number of years ago, when I had an exhibition of my work, the people in charge who came to pick up my manuscripts saw them piled up haphazardly in the garage, and were shocked. “What?! They’ll grow mold like this!” they said. People who do things properly apparently make a dedicated manuscript room, where they can control humidity. I have no interest in that, though. (laughs)

Wired: Do you suddenly grow cold towards them?

Toriyama: Well, at any rate, I have no attachment to something once I’ve drawn it. So I often get letters from readers saying, “This is different from what you said before”.2

■ I want you to understand the bits of poison that slip in and out of sight

Wired: With regards to Jump‘s famous popularity poll system, is it very strict?

Toriyama: It is. Only, sending postcards is usually done with the objective of getting the prizes [drawn from among respondents]. Adults generally don’t fill in those questionnaires and send them in, right? The prizes are aimed at kids, after all. So, I think it’s a bit disadvantageous for those cartoonists who draw stories aimed at adults. I think that the way to read the votes is something they fret about in the editorial department, as well. After all, there are cases where the votes don’t come in at all, yet the Comics [i.e., tankōbon] still sell.

Wired: Were you ever very discouraged by the popularity polling system?

Toriyama: I’m the kind of person who doesn’t worry about it too much, but if [the response] was extremely bad, there were times when I’d think, “I wonder why?”. And also, I myself an extremely twisted person. So if, on a reader’s postcard, it was written “That’s this, and this’ll happen like this”, then I’d deliberately go with a development where that didn’t happen, and if a certain character got fairly popular, I’d deliberately kill him. (laughs) Since I did it half-cocked without deciding [what would happen] up ahead, it was easy enough to change up that sort of thing as the circumstances warranted. Even with characters that appear to be doing the right thing at first glance….

Wired: There’s actually “poison” inside?

Toriyama: Right. There’s how, basically, Son Goku from Dragon Ball doesn’t fight for the sake of others, but because he wants to fight against strong guys. So once Dragon Ball got animated, at any rate, I’ve always been dissatisfied with the “righteous hero”-type portrayal they gave him. I guess I couldn’t quite get them to grasp the elements of “poison” that slip in and out of sight among the shadows.

Wired: Perhaps that’s because it’s animation aimed at children, after all?

Toriyama: Well, that might be some of it, too.

Wired: How do you strike a balance between the readers’ expectations and the things you want to draw?

Toriyama: Well, basically, I’m always coming up with ideas for mixing the things I want to draw with things targeted at children. But I have no experience with actually being a hit [with readers] when I aim to. (laughs) On the contrary, the ones where I think, “I don’t wanna draw this,” are the ones that make it. (laughs) I have mixed feelings about that. For instance, even with Dr. Slump, it was originally a mad-scientist story. So when I was told, “Draw it with the girl as the main character,” I naturally….

Wired: The main character was originally Senbei Norimaki.

Toriyama: Right, and Arale-chan was nothing more than one of Senbei’s inventions. I really was resistant to having a girl as the main character in a boys’ magazine.

■ Comics are purely “entertainment”

Wired: What are your thoughts on the exclusive-contract system for cartoonists at major publishers, as typified by Shueisha?

Toriyama: In my case, I’m in a situation where I do almost everything by myself, so the time I can use is pretty much set, and [material for] Jump alone is plenty. I don’t have much in the way of wants, either. At any rate, I just think, “[I’ll be happy] if I can draw a good comic”.

Wired: Is the fact that the place you draw for is Jump not particularly meaningful to you, Toriyama-san?

Toriyama: It isn’t. I can only draw for one place, so I don’t care what that one place is.

Wired: I see. But if you flip the statement, “It doesn’t matter to me where [my work] is published”, couldn’t it also be heard as saying that the current comics magazines are only different in terms of publishers, and that the magazines have no individuality?

Toriyama: In the end, while I say this or that, the fact that I’m with Shueisha also has to do with the fact that the way other editorial departments do things just wouldn’t suit me. The kind of production method where a braintrust decides on the story in advance, then says, “Now, who should we pick to work on it?” is absolutely not for me, after all. And also, I don’t have any plans to do a weekly serial after this, at present. So there’s also the fact that, in spite of that, I’ve got the understanding of Shueisha that “It’s all right to do things at your own pace to a certain extent”.

Wired: And if you had to give Shueisha your unvarnished thoughts?

Toriyama: There was one point where I did step in a bit to defend [the magazine] for a little while. It felt like they were pandering to the public. To put it simply, there were things like running biographical comics on Nobel laureates to go along with the announcement of the Nobel Prize, and when it seemed like bullying [in schools] had become a problem, running a comic about the bullying issue. I think it’s fine to have those things, but I also think it’s not something that you should make into a strategy for the magazine. I believe that comics magazines are purely entertainment, after all. And also, there had gotten to be a trend of, “If you show a little bit of nudity, your serial will be immediately canceled”. I thought, “I should have pushed harder against it.”

Wired: When did that start?

Toriyama: It had felt like that to me for the past three years or so. I think it’s gotten quite a bit better recently, though.

Wired: By the way, what made you become a cartoonist in the first place?

Toriyama: Money. (laughs) I wanted the prize money, to be perfectly honest. I was going to quit drawing comics if I had managed to get the prize money, after all.

Wired: That was your reason?

Toriyama: Well, now, I do of course think that this in itself is probably one of the more enjoyable jobs, though. (laughs)

AKIRA TORIYAMA

Born in 1955 in Nagoya. After working at an advertising production company, he began drawing comics at 23, and continuing on from Wonder Island and Detective Gal Tomato, Dr. Slump began serialization in Weekly Shōnen Jump in January 1980. It became an animated TV show in April of the next year, and the main character Arale-chan gained explosive popularity. After that, he drew the Dragon Ball series in Jump, attracting popularity not just domestically, but overseas as well. In 1982, he received the Shogakukan Manga Award.

2 i.e., since he doesn’t go back and check his work, he makes continuity mistakes